The first time we saw Paris was in April . . . and it snowed. The Missus and I were expecting chestnuts in blossom; instead, we got snowflakes and then some.

Since the Missus had packed nothing heavier than a jeans jacket, that was also the first of many visits to international shopkeepers in search of emergency accessories to keep her warm. (See also our encounters with the Mistral on the French Riviera and a Biblical rainfall in Munich for further details.)

From the mid-’80s to the mid-’90s, our trips to Paris were pretty evenly divided between spring and fall, as the Missus attended the European fabric shows so she could work her special magic predicting future trends for U.S. shoe manufacturers.

But starting in 1998 – and for the next ten years – we only went to Paris during Thanksgiving week. What changed was my job: I started working for WGBH-TV’s Greater Boston, a nightly news and public affairs program. At first I was the show’s sole reporter, then its managing editor, and finally its executive producer. Each role required me to restrict vacations to the program’s annual August hiatus, which of course was no time to visit Paris, since even Parisians don’t want to be there in August.

So the Missus and I would pop over for Thanksgiving. After our maiden visit to Paris, during which we stayed at a snooty Left Bank hotel (scene of The Great Orange Juice Shakedown of 1985), we cycled through a bunch of hotels on Île Saint-Louis: Hotel Du Jeu De Paume, Hotel Des Deux-Iles, and Hôtel Saint-Louis-en-l’Isle, where we were relegated to a top-floor room that could have made Toulouse-Lautrec wish he were shorter.

At the start of our ten-year stretch of Thanksgiving trips, we settled on the Hotel Saint-Louis Marais, which “combines the quaint, old-world charm of an ancient townhouse with all the comforts and conveniences of a modern hotel.” During that time, we watched the hotel upgrade from charming but basic rooms to more polished accommodations like this.

We also watched one night as an EMT crew lowered a dead guy on a stretcher out a third-story window of the apartment building across rue du Petit Musc. Extremely dramatic but strictly a one-off, for those of you keeping score at home.

Coincidentally, right around the corner at 20 rue Saint-Paul sat this establishment.

The Missus and I must’ve walked past that storefront a hundred times, and all the while I assumed it was a restaurant. But it was in fact a specialty grocer, as this Yelpster detailed in 2011.

Thanksgiving is heaven for the American expat missing Betty Crocker and Duncan Hines cake mixes (plus ready-to-spread icings), Pop Tarts, BBQ sauce, Lipton French onion soup mix, maple syrup and peanut butter.

Sure these imported indulgences won’t come cheap but can you really put a price on being able to make (and eat) a pan of Rice Krispies Treats® in Paris?

Others yelped less effusively: “Staff was extremely rude . . . absurdly high prices . . . I could find almost all of the products that they sell at my local Leclerc supermarket for 1/4 of the price.” So in skipping Thanksgiving The Store, we didn’t miss much, especially in the wallet.

We tried, however, not to skip Thanksgiving The Day, or to be tight-fisted about it. For example, one Turkey Day we lunched at Versailles and dined at the Musée d’Orsay’s la-di-da restaurant (neither meal, I should point out, included turkey).

The d’Orsay’s dining room was something else.

In the heart of the former train station, the Musée d’Orsay Restaurant is a magnificent reference to French tradition, with frescoes by Gabriel Ferrier and Benjamin Constant lining the ceilings of the grand dining room and its salon.

The chandeliers, the painted ceilings and the gilding of this room classified as a historical monument, will make this unique moment you spend here unforgettable.

Also memorable was the mini-drama that unfolded at the table next to us, where what appeared to be a hybrid family of eight was sulking its way through a wildly expensive dinner. The action centered around the stepmom, who was blatantly less interested in her husband than in his young adult son. Safe to say, the Missus and I were the only ones disappointed when the check finally arrived at their table.

Other Thanksgiving meals were more modest, but no less entertaining. At a Chinese restaurant on rue Saint-Paul called The Purple Dragon, we caught a different mini-drama between a young, highly distraught woman and an older man she constantly referred to as DA-dee, even though it was clear they were related only by money.

(On a subsequent visit there we saw a mouse scurry across the back of the bar, which a) marked our final meal at that particular establishment, and b) ensured that The Purple Dragon would forever after be known as La Souris Brune.)

A mini-drama of a different sort unfolded Thanksgiving week of 2004. The Missus and I had just landed at Charles de Gaulle Airport and were killing time until we could check into our hotel room. So we went to check out Matisse Picasso, a spectacular exhibit that had debuted at the Tate Modern, moved on to MoMA, and wound up in Paris.

I was totally jet-lagged and practically out on my feet as I staggered through the exhibit. But then I spotted something that snapped me to attention: the junior senator from Massachusetts, John Forbes Kerry.

It was just a few weeks after he had lost his presidential race against George W. Bush. I had covered the Kerry campaign extensively – and quite critically – for WGBH’s Greater Boston, much to the displeasure of Long Jawn.

We caught sight of one another at roughly the same time, but with decidedly different reactions: I smiled and started toward him; Kerry scowled and scurried away.

Score one for a free press.

The best mini-drama, though, was the one that featured me and the Missus. We were sitting in a small restaurant on Île Saint-Louis; a few tables away from us sat two imperious looking women impatiently searching for the waiter. He eventually emerged, handed us two menus in French and gave the women two English menus, much to their immediate outrage. I still recall that dinner as the most satisfying meal of our entire trip.

• • • • • • •

Thanksgiving week was an in-between time to be in Paris: The city was not yet decked out for Christmas, but – after a long summer of bumptious American tourists – was in no mood to give thanks for any more of them.

The Paris cityscape was equally severe in late fall, the trees all “bare ruin’d choirs, where late the sweet birds sang,” to borrow from the Bard.

Happily, after I left TV news for radio commentary in 2008, the Missus and I were able to return to Paris twice in the springtime. On those two trips the city looked entirely different. At first we couldn’t figure out why, but then it dawned on us: We couldn’t see the Paris cityscape – the buildings were mostly blocked by the trees in re-leaf, where again the sweet birds sang.

We could, however, see the Jardin des Plantes in full bloom, as this video of the former royal garden nicely illustrates.

While we were in the neighborhood, we also moseyed through Musée de la Sculpture en plein air.

The open-air sculpture museum along the Quai Saint-Bernard between the Pont de Sully and the Pont d’Austerlitz provides a pleasant art lover’s interlude in the course of a stroll along the banks of the Seine. Opened in 1980 in the Square Tino Rossi, the museum displays sculptures by famous artists including César, Constantin Brancusi, Nicolas Schöffer and Émile Gilioli.

You’ll find more outdoor artworks here, including these.

We also enjoyed exploring Luxembourg Gardens, “a 17th-century park with formally laid-out gardens, tree-lined promenades, a number of statues, model sailboats on its Grand Basin, and the Luxembourg Palace,” all of which this lovely video depicts.

Our favorite park by far was a small patch behind Notre-Dame Cathedral. We had eventually decamped from the Hotel Saint-Louis Marais to a variety of apartments in the Marais district, from which we would stroll after dinner to Île de la Cité via the Pont Saint-Louis. There we were lucky enough to encounter the Borsalino Jazz Band at the end of the bridge.

You bet we forked over ten euros for their CD, which we play regularly to this day. (Lots more music from those wonderful street musicians here.)

Just to the left of the quartet you can see the edge of Square Jean-XXIII, where we sat many an evening saluting the end of the day.

It became one of our favorite parks in Paris because it actually featured flowers, unlike so many of the city’s over-regimented gardens (lookin’ at you, Jardin des Tuilieries). For example . . .

Sadly, after the tragic fire at Notre-Dame in April 2019, the Cathedral and Square Jean-XXIII were closed for the next five years. A double loss, non?

Happily, the resplendently reborn Cathédral Notre-Dame de Paris was unveiled to the world in December 2024. Square Jean-XXIII will have to wait another five years for its rebirth, which is set to be completed in 2030.

• • • • • • •

The apartment in the Marais that we rented most often was in Place Ste. Catherine, which we came to dub Place de Dîner (Trip Advisor: “This must be one of the most picturesque and untouched corners of Paris. Lots of small and reasonably priced cafes and restaurants frequented by locals.”)

Funny thing was, we ate dinner in Place de Dîner maybe once during each of the three times we stayed there. Far more often we found ourselves back at the apartment for lunch on days we were cruising nearby attractions.

On one such occasion, as the Missus and I sat at our table for two by casement windows swung wide to a warm afternoon, we turned on the TV to watch the French Open quarterfinal match between the #2 seed Roger Federer and the #11 seed – and hometown favorite – Gaël Monfils.

Early in a tight first set, the broadcast cut to the plaza outside Hôtel de Ville, where a crowd had gathered to watch the match on a supersize video screen.

“Hey,” the Missus exclaimed. “That’s right down rue de Rivoli. Let’s go.”

We did, and we arrived there just in time for the first-set tiebreaker, in which the crowd went increasingly wild until Federer fought off a set point and prevailed 8-6. He then dispatched Monfils 6-2, 6-4 for the victory, after which he went on to win his sole Roland Garros title, largely because the clownish Robin Soderling had inexplicably bested four-time defending champion Rafael Nadal in the fourth round. Afterward, Nadal explained his defeat this way: “I lost my calm.”

Federer-Monfils at Hôtel de Ville, by contrast, was anything but calm.

It was a total gas.

• • • • • • •

During one of our springtime returns to Paris, we took advantage of the mild weather to re-visit Cimetière du Père Lachaise, the city’s most celebrated burial ground.

The Père Lachaise cemetery takes its name from King Louis XIV’s confessor, Father François d’Aix de La Chaise. It is the most prestigious and most visited necropolis in Paris. Situated in the 20th arrondissement of Paris, it extends 44 hectares and contains 70,000 burial plots. The cemetery is a mix between an English park and a shrine. All funerary art styles are represented: Gothic graves, Haussmanian burial chambers, ancient mausoleums, etc. On the green paths, visitors cross the burial places of famous men and women; Honoré de Balzac, Guillaume Apollinaire, Frédéric Chopin, Colette, Jean-François Champollion, Jean de La Fontaine, Molière, Yves Montand, Simone Signoret, Jim Morrison, Alfred de Musset, Edith Piaf, Camille Pissarro and Oscar Wilde are just a few.

Representative samples . . .

And then there was Jim Morrison’s gravesite. The first time the Missus and I saw it, the legendary musician’s grave was surrounded by a sea of graffiti and a United Nation of stoners hanging about, smoking dope, and engaging in the ritual sacrifice of Doors audio cassettes.

Periodic clean-up efforts began in 1991, initiated by Jim Morrison’s family upon the 20th anniversary of his death by apparent overdose.

This is the end the family wanted.

Similar glow-ups are now being initiated in several of the city’s burial grounds. Because maintenance of gravesites in Parisian cemeteries is the responsibility of families, many of the oldest ones have fallen into disrepair. So local officials launched a lottery, offering Parisians a shot at a burial site at Père Lachaise, Montparnasse, or Montmartre if they agree to restore one of ten decrepit gravestones, often without legible inscriptions, in those cemeteries.

(In other restoration news, the Los Angeles Times has reported that “a memorial bust of the late Jim Morrison that disappeared from his Paris grave site nearly four decades ago was recently recovered by Paris police.” That’s a relief, eh?)

While Père Lachaise is certainly spectacular, our favorite Paris boneyard was the far more modest Cimetière des Chiens et Autres Animaux Domestique – the oldest public pet cemetery in the world, as Sophie Nadeau relates at Solo Sophie.

[The cemetery] lies a little outside Paris- less than half an hour by metro. Situated in Asnières-Sur-Seine, the Paris Pet Cemetery was founded in 1898.

Although many might believe that the cemetery was started for sentimental reasons, it was actually founded for health ones. In 1898, a law was passed that meant that Parisians were no longer allowed to bury their pets wherever they liked.

People were even just throwing their bodies away in the garbage or discarding them in the Seine! The new law dictated that animals had to be buried at least 100m away from housing and under at least 1m of earth. And thus, the Paris Pet Cemetery was born.

The Missus and I took the M13 metro to the Gabriel Péri stop and walked 15 minutes to the cemetery. A black cat awaited us there – we christened him Methuselah or Mephistopheles, can’t remember which – and he promptly led us on a tour from one grave (“Brave Nikki”) to another (“Chere Chou-Chou”) to another (the one with a clear plastic globe filled with tooth-marked tennis balls).

Here’s a more recent tour. The Missus and I should ever get such elaborate – and expensive – headstones, yeah?

Toward the end of our visit, we noticed an elderly woman who was lingering at one of the gravesites and holding a small, presumably replacement, dog nestled inside her coat. It was oddly touching, accent admittedly on the odd.

Many springtimes later, our Laid-to-Rest Tour took us to the Hôtel National des Invalides.

In the 17th century, Louis XIV was the head of Europe’s greatest army. Aware that soldiers were the primary guardians of France’s greatness, the Sun King decided to erect a building for those who had served the royal army. The Cité des Invalides first opened to veterans in 1674. At once a hospice, barracks, convent, hospital and factory, the Hôtel was a veritable city, governed by a military and religious system. Over 4,000 boarders lived within the site’s walls.

Today, the Hôtel still fulfills its initial function by housing the Institution Nationale des Invalides.

It also houses the Tomb of Napoleon I in the Dôme des Invalides.

Under the authority of Louis XIV, the architect Jules Hardouin-Mansart had the Invalides’ royal chapel built from 1677 onwards. The Dome was Paris’ tallest building until the Eiffel Tower was erected. The many gilded decorations remind us of the Sun King who issued an edict ordering the Hôtel des Invalides to be built for his army’s veterans.

During the Revolution, the Dome became the temple of the god Mars. In 1800, Napoleon I decided to place [Henri de La Tour d’Auvergne, vicomte de] Turenne’s tomb there and turned the building into a pantheon of military glories.

In 1840, Napoleon had been buried on Saint Helena Island since 1821, and King Louis-Philippe decided to have his remains transferred to Les Invalides in Paris. In order to fit the imperial tomb inside the Dome, the architect [Louis] Visconti carried out major excavation work. The body of the Emperor Napoleon I was finally laid to rest there on 2 April 1861.

Here’s a nice meander through the imperial tomb, if you’re so inclined.

Not surprisingly, the Missus and I felt far more at home in the pet cemetery.

• • • • • • •

Also not surprisingly, we took in multiple art exhibits during those springtime Paris trips, starting with The Jazz Century at Musée du Quai Branly in 2009.

Jazz constitutes one of the major artistic events of the 20th century. This music, which appeared in the first years of the century, is more than a mere musical genre. It revolutionized the world of music and also initiated a new way of being in 20th century society.

the world of music and also initiated a new way of being in 20th century society.

From its African-American roots, jazz quickly became universal by introducing artistic influences from Africa, America and Europe and had a profound influence on the history of art in the last century. Throughout the 20th century jazz in effect became more a major symbol and a source of inspiration and creativity than a phenomenon or passing trend.

Universally recognisable, jazz is not only a type of music, it is also a state of mind that has influenced a number of artistic fields. Painting, literature, photography, film, graphic design and other 20th century forms of art bear the marks of jazz to different extents depending on the particular moment in time.

The museum’s press release laid out the extensive timeline of the exhibit, from “The ‘Jazz Age’ in America 1917-1930” to “Harlem Renaissance 1917-1936” to “The ‘Jazz Age’ in Europe 1917-1930” and beyond – ten chronological sections in all.

The Guardian featured a terrific gallery of artworks from the exhibit, including “Josephine Baker au Bal Negre” by Kees van Dongen, 1925; “Blue Lights Volume 1, Kenny Burrell” by Andy Warhol, 1958; and “Jazz (Variante)” by Fernand Léger, 1930.

Also on exhibit at that time was Valadon-Utrillo, Au tournant du siècle à Montmartre, De l’impressionnisme à l’Ecole de Paris at the Pinacotheque de Paris. Here’s how Karin Badt described it at France Revisited.

“It makes no sense to compare,” Marc Restellini, director of the Pinacothèque de Paris in Paris told me when I asked him why Maurice Utrillo was the famous painter of Montmarte while his mother Suzanne Valadon has generally been forgotten. Restellini’s exhibit . . . places the mother-son paintings side-by-side. Viewing it raise for me the question as to why one painter was once considered “better” than the other. It’s also interesting to see how two people from the same family saw the world differently.

The Valadon-Utrillo exhibit portrays the two equally, suggesting a life-long and mutual mother-son influence. Utrillo’s empty landscapes of buildings and streets, haunted by a sense of loneliness, hang next to the bold paintings of his mother, with their extra-bright trees outlined in dark strokes.

The two artists, despite sharing an odd sensibility, seem to have only one aesthetic in common: at times, a similar choice in pastels. “Obviously,” Restellini told me. “They shared the same palette.” Yet aside from this vague similarity, the two are dramatically different.

Suzanne Valadon, Badt wrote, “is known for her nudes which really are ‘nakeds.’ They present no airbrushed prettiness, but slumps and curves and wrinkles. She dared to paint what she saw, a scandalous choice for a woman, it seems.”

Maurice Utrillo, by contrast, was “a drunk since age 9, in despair because his sexy adventurous mother often left him alone as she pursued her art and her loves.” Valadon also had him “shunted to insane asylums all his life,” mostly at the behest of her rich businessman husband.

His paintings are typically landscapes of edgy stillness: buildings and streets. “The walls of Utrillo have a painful secret,” Jean Fabris, curator and long time-friend of Utrillo’s widow, told me that a critic once told him. “They have the odor of piss.”

That Pinacotheque exhibit just might have been the closest mother and son ever got.

A few blocks away, the Grand Palais featured the blockbuster exhibit Le Grand Monde d’Andy Warhol, as Joachim Pissarro detailed in Artforum.

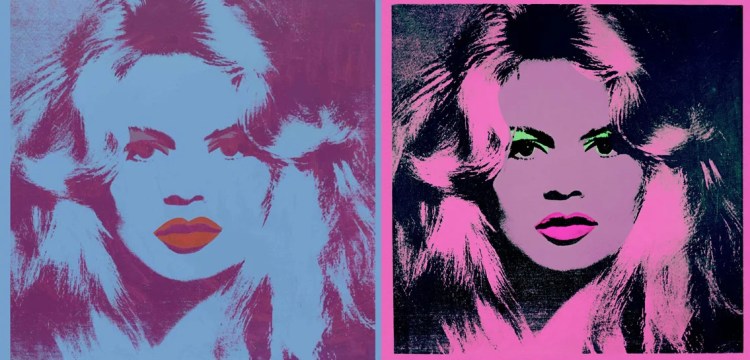

With an ingenuous but almost untranslatable title, “Le Grand Monde d’Andy Warhol” expands on two floors of the Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais in Paris. (Translated by the museum as “Warhol’s Wide World,” the English title fails to capture the double entendre of “high society” that the phrase “grand monde” entails.) Comprising more than four hundred paintings, photographs, Polaroids, films, and other docu- ments, this vast exhibition brings together the largest number of Warhol portraits ever shown. Portraits of living subjects, almost always commissioned, are seen in the wider context of three other genres: posthumous portraits of figures from the world of cinema (e.g., the “Marilyn” series of 1962, Judy Garland, ca. 1979, or Hitchcock, 1983); portraits of celebrities executed from media sources (e.g., Jackie, 1964, Four Marions, 1966, or the seldom seen Brigitte Bardot diptych, 1974, derived from a Richard Avedon photograph); and portraits of iconic historical or religious figures, such as Mao, 1973 (of which Warhol produced almost innumerable versions) and the monumental Last Supper (Christ 112 Times), Yellow, 1986, which closes the exhibition.

“high society” that the phrase “grand monde” entails.) Comprising more than four hundred paintings, photographs, Polaroids, films, and other docu- ments, this vast exhibition brings together the largest number of Warhol portraits ever shown. Portraits of living subjects, almost always commissioned, are seen in the wider context of three other genres: posthumous portraits of figures from the world of cinema (e.g., the “Marilyn” series of 1962, Judy Garland, ca. 1979, or Hitchcock, 1983); portraits of celebrities executed from media sources (e.g., Jackie, 1964, Four Marions, 1966, or the seldom seen Brigitte Bardot diptych, 1974, derived from a Richard Avedon photograph); and portraits of iconic historical or religious figures, such as Mao, 1973 (of which Warhol produced almost innumerable versions) and the monumental Last Supper (Christ 112 Times), Yellow, 1986, which closes the exhibition.

Once again The Guardian provided a wide-ranging gallery of works in the show. That assemblage, however, did not include . . .

Man, that was one eye-popping trip from start to finish.

• • • • • • •

It would be eight more years before the Missus and I returned for one last springtime in Paris (in the interim we’d gotten sidetracked by two fabulous trips to the Côte d’Azur). What we found in May of 2017 was an amazing bounty of art exhibits around Paris.

Let’s begin at Musée Picasso, since so much of 20th century art sprang from the hand of that larger-than-life Spaniard. On display when we arrived was Olga Picasso, “the first exhibition dedicated to the years shared between Pablo Picasso and his first wife, Olga Khokhlova.”

As the perfect model during Picasso’s classical period, Olga was first portrayed by thin, elegant lines characterized by the influence of the French neoclassical painter Ingres. Synonymous with a certain return to figuration, Olga is often represented as melancholic, sitting, while  reading or writing . . .

reading or writing . . .

After the birth of their first child, Paul, on February 4, 1921, Olga became the inspiration for numerous maternity scenes, compositions bathed in innocent softness. The family scenes and portraits of the young boy show the serene happiness which flourishes notably in timeless shapes. These forms correspond to Picasso’s new attention to antiquity and the renaissance discovered in Italy, which was reactivated by the family’s summer holiday in Fontainebleau in 1921 . . .

After the encounter in 1927 with Marie-Thérèse Walter, a 17-year-old woman who will become Picasso’s mistress, Olga’s figure metamorphoses. In Le Grand nu au fauteuil rouge (1929), Olga is nothing but pain and sorrow. Her form is flaccid with violent expression and translates the nature of the couple’s profound crisis.

Here’s how that played out on canvas.

Ouch.

Several outstanding private collections were also on display during our trip, starting with this exhibit at the Musée Maillol.

The 21 rue La Boétie exhibition retraces the unique career of Paul Rosenberg (1881-1959), who was one of the greatest art dealers of the first half of the 20th century. It brings together some sixty masterpieces of modern art (Pablo Picasso, Fernand Léger, Georges Braque, Henri Matisse, Marie Laurencin, etc.), some of which have never been seen before in France and come from major public collections such as the Center Pompidou, the Musée d’Orsay, the Picasso Museum in Paris, or even the Deutsches Historisches Museum in Berlin . . .

Valérie Guédot at Radio France provided this 1914 quote from Rosenberg: “I am soon opening new galleries of Modern Art, 21, rue La Boétie , where I intend to hold periodic exhibitions of the Masters of the 19th century and painters of our time. However, I believe that the fault with current exhibitions is to show the work of an artist in isolation . . . Many people, who are not sure enough of their taste or of the taste of the Artists, taken separately, would see their task facilitated by enjoying an overview of the close union of all the Arts in the atmosphere of a private dwelling.”

The Musée Maillol show certainly reflected that sensibility. Representative samples from Georges Braque, Marie Laurencin, Fernand Léger, and Pablo Picasso . . .

Across the Seine, the Petit Palais was hosting De Watteau à David, la Collection Horvitzt, which Financial Times critic Humphrey Wine described as “a triumph”, although I’m pretty sure we didn’t see it.

We definitely did, however, see From Zurbarán to Rothko. Alicia Koplowitz Collection at Musée Jacquemart André.

The exhibition pays tribute to one of the most prolific collectors of our time. The fifty-three works shown here retrace her tastes and the choices she has made over a period of thirty years, and invite us to share in the emotion of the collection. Beyond the diversity of technique, epochs and styles, the works in the Alicia Koplowitz Collection – Grupo Omega Capital all share the same artistic sensibility. They bear witness to a subtle but confident, audacious taste, with a certain penchant for female portraits. Whether she is the model or artist, the creator shaping the material or the inspiring muse, woman is at the heart of the majority of these artworks.

Here’s the exhibition’s teaser video. It’s an amazing collection, from “The Virgin and Child with the Infant Saint John the Baptist” (c. 1659), by Francisco de Zurbarán . . .

to Egon Schiele’s “Femme à la robe bleue” (1911) . . .

to Mark Rothko’s “N°6 (Yellow, White, Blue over Yellow on Gray)” 1954.

Musée Bourdelle featured a collection of a very different kind: Balenciaga – L’Oeuvre au noir. The Cut’s Sarah Moroz wrote about “the designer’s clever and complex use of the color black.”

Although vivid palettes also characterize the famed designer’s work, Balenciaga was heavily  swayed by the folklore of his Spanish origins, from mourning dress to bullfighter costumes to monastic robes. Balenciaga’s mastery of volumes and technique — from the barrel line (1947) to the tunic dress (1955) — made him a pioneer, all the more evident when viewed through a monochrome lens. As Véronique Belloir, director of haute-couture collections at the Palais Galliera and curator of the show, puts it: “Revisiting Balenciaga’s work without the distraction of color enables us to focus our gaze on the essentials, and enter into the subtlety of his materials and execution.” In 1938, Harper’s Bazaar in fact described Balenciaga black as “almost velvety, a night without stars, which makes the ordinary black seem almost grey.”

swayed by the folklore of his Spanish origins, from mourning dress to bullfighter costumes to monastic robes. Balenciaga’s mastery of volumes and technique — from the barrel line (1947) to the tunic dress (1955) — made him a pioneer, all the more evident when viewed through a monochrome lens. As Véronique Belloir, director of haute-couture collections at the Palais Galliera and curator of the show, puts it: “Revisiting Balenciaga’s work without the distraction of color enables us to focus our gaze on the essentials, and enter into the subtlety of his materials and execution.” In 1938, Harper’s Bazaar in fact described Balenciaga black as “almost velvety, a night without stars, which makes the ordinary black seem almost grey.”

Haute couture at Musée Bourdelle demanded a haute entry fee, so the Missus went solo to the exhibit and I went down rue Antoine Bourdelle to a café, where I sat at a sidewalk table and read a magazine while I waited for a waiter/waitress to arrive . . . and waited . . . and waited . . . and no one ever did.

Then the Missus came along and we headed to the Metro and our next stop.

• • • • • • •

Now might be a good time to talk about the Paris we encountered in that spring of 2017.

The Missus and I had been to the City of Light Service almost a dozen times from the late ’80s through the Aughts. In all those years, there was exactly one time we weren’t happy to be there – one rainy afternoon in the mid-’90s when we’d run out of things to do and were thisclose to breaking down and going to Euro Disney, which is truly the White Flag of French Tourism.

Instead, we went au cinema and watched The Big Sleep with French subtitles.

Other than that afternoon, Paris had always possessed an air of magic for us.

Until our 2017 trip.

That Paris was different: It had less sparkle, more streets torn up, more panhandlers on the sidewalks, more danger in the air. When we went to sit in Square Jean-XXIII, there were soldiers with Uzis patrolling the gardens. When we went to the Louvre, intending to see the Vermeer show, we were afraid – given the Nice truck attack from a year earlier – to stand in the long line snaking up to the security checkpoint outside the Pyramid. We were never really comfortable on that trip. There was, sadly, never any magic.

If anything, the city was even less hospitable than usual, if hospitality can be measured in negative terms. That freeze-out at the café on rue Antoine Bourdelle was the second time I’d been shunned by a so-called serving staff. A few days earlier, while the Missus was at fine stores everywhere along rue de Rivoli, I sat at another sidewalk café, reading a magazine and being totally ignored by the waitstaff buzzing around all the other tables.

Forget magic – at that point I would gladly have settled for a café crème.

• • • • • • •

Borderline magical, on the other hand, was Beyond the Stars. The Mystical Landscape from Monet to Kandinsky at Musée d’Orsay.

Seeking an order beyond physical appearances, going beyond physical realities to come closer to the mysteries of existence, experimenting with the suppression of the self in an indissoluble union with the cosmos… It was the mystical experience above all else that inspired the Symbolist artists of the late 19th century who, reacting against the cult of science and naturalism, chose to evoke emotion and mystery.

The landscape, therefore, seemed to these artists to offer the best setting for their quest, the perfect place for contemplation and the expression of inner feelings.

Many more inner feelings ensued.

Outer feelings were the order of the day for MEDUSA: Jewellery and Taboos at Musée d’Art moderne de la Ville de Paris. The art and design website ITSLIQUID provided a smart introduction to the exhibit.

The Musée d’Art moderne de la Ville de Paris presents MEDUSA, an exhibition taking a contemporary and unprecedented look at jewellery, unveiling a number of taboos. Just like the face of Medusa in Greek mythology, a piece of jewellery attracts and troubles the person  who designs it, looks at it or wears it. While it is one of the most ancient and universal forms of human expression, jewellery has an ambiguous status, mid-way between fashion and sculpture, and is rarely considered to be a work of art . . .

who designs it, looks at it or wears it. While it is one of the most ancient and universal forms of human expression, jewellery has an ambiguous status, mid-way between fashion and sculpture, and is rarely considered to be a work of art . . .

The exhibition brings together over 400 pieces of jewellery: created by artists (Anni Albers, Man Ray, Meret Oppenheim, Alexander Calder, Louise Bourgeois, Lucio Fontana, Niki de Saint Phalle, Fabrice Gygi, Thomas Hirschhorn, Danny McDonald, Sylvie Auvray…), avant-garde jewellery makers and designers (René Lalique, Suzanne Belperron, Line Vautrin, Art Smith, Tony Duquette, Bless, Nervous System…), contemporary jewellery makers (Gijs Bakker, Otto Künzli, Karl Fritsch, Dorothea Prühl, Seulgi Kwon, Sophie Hanagarth…) and also high end jewelers (Cartier, Van Cleef & Arpels, Victoire de Castellane, Buccellati…), as well as anonymous, more ancient or non-Western pieces (including prehistorical and medieval works, punk and rappers’ jewellery as well as costume jewellery etc.).

Other ornaments from the exhibit . . .

Finally, there were a couple of twofers in town at the time – one modest, one major.

In the case of the former, Camille Pissarro was having a moment in Paris, starting with a retrospective at the Musée Marmottan Monet, as Martin Bailey detailed at The Art Newspaper.

The first career survey of Camille Pissarro in Paris since 1981 opens this month at the Musée Marmottan Monet. It presents 75 of his greatest paintings, beginning with a seascape from his youth in the Danish West Indies, Two Women Talking by the Sea, St Thomas (1856), borrowed from the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

Pissarro was the first of the Impressionists, painting landscapes outdoors using bright colours and a vibrant technique. Although only 43 when he helped establish the Impressionist movement, his grey beard meant that he soon came to be regarded as its elderly leader. Paul Cézanne, although only nine years younger, described Pissarro as “a father for me”. This paternal figure is captured in an evocative self-portrait done in Pissarro’s old age (around 1898) owned by the Dallas Museum of Art. He was the only member of the group to show at all eight Impressionist exhibitions held between 1874 and 1886.

Here’s that 1898 self portrait, for those of you keeping score at home.

And here’s a brisk walk through the exhibit.

Impressionism’s OG was also celebrated at the Musée du Luxembourg with the exhibit Pissarro in Éragny: Nature Regained. Heidi Ellison at Paris Update provided a personal perspective on the show.

I have often been struck by the luminous beauty of a painting by Impressionist Camille Pissarro (1830-1904) when I come across his work in a group show, but “Pissarro à Éragny: La Nature Retrouvée” at the Musée du Luxembourg is the first monographic exhibition I have seen of his work.

The show concentrates on the paintings and drawings he made from the time he moved to the village of Éragny in Normandy in 1884 until he died. The place was a constant inspiration to him, and he never stopped painting the surrounding countryside in every light and every season.

Although Pissarro was an active, card-carrying Impressionist, a couple of years after moving to Éragny, he started working in the Neo-Impressionist style, but after a while gradually returned to Impressionism.

Ellison noted that Pissarro had another calling card as well: “Surprisingly, perhaps, this painter of delicate, peaceful landscapes was politically a fervent anarchist, but his anarchism had nothing revolutionary about it; it consisted mostly of a great empathy for workers and a belief in equality for all.”

Toward that end, Ellison added, “[in] 1889, he made an album of ink drawings entitled ‘Turpitudes Sociales’ illustrating the ‘misery and oppression’ of urban workers, not for publication but just to educate his large family (he had eight children, six of whom survived to adulthood).” The Clark Art Institute in Williamstown highlighted the album in its 2011 exhibition, Pissarro’s People.

Back in Paris, the other twofer revolved around the 100th anniversary of Auguste Rodin’s death. The main event was Rodin: the centennial exhibition at the Grand Palais, featuring over 200 of Rodin’s works along with assorted sculptures and drawings by the likes of Picasso, Matisse, and Giacometti, Here’s a tour of the exhibit, which for the life of me I can’t remember seeing.

I am sure, though, that the Missus and I caught the Kiefer-Rodin exhibit at Musée Rodin, which had undergone a $17 million renovation two years earlier. Anselm Kiefer was given “carte blanche” to install an exhibition that “[demonstrated] the unusual convergence of these two giants, shaped with freedom and liberated from all artistic contingencies.”

The similar backgrounds, sources of inspiration and creative processes between Kiefer and Rodin reveal an instinctive originality. Drawn by the accidental, open to chance, they exploit all domains, manipulate all materials, heading off the beaten path and allow themselves a myriad of arrangements and daring transformations. Drawn by the debris and offcuts directly resulting from Rodin’s sculpture style, which he combines with relics of his own life and other unusual materials, Anselm Kiefer produces a series of entirely unprecedented displays.

The museum posted this overview of the installation. And with that exhibit our viewing was over, and we said au revoir, Paris, very likely for the final time.