Over the past four decades there have been – scattered across our many journeys like sprinkles atop an ice cream cone – the numerous trips the Missus and I have made to The Big Town.

From the mid-’80s through the mid-’90s, we traveled there several times a year for the Missus to deliver her trend forecasting and product development insights to her myriad – and extremely lucky – footwear manufacturing clients.

Other times during those years we went just for the fun of it, drinking in the museums, the art galleries, the theatrical productions, and the coffee shops.

For the most part we traveled to New York on the Eastern Airlines Shuttle, which launched in 1961 and offered hourly departures from Boston to New York for around $12. By 1986 the flight cost more like 60 bucks – which is $166 in today’s dollars (plus the four cab fares to and from Logan and LaGuardia) – but that was okay, because here’s what Eastern’s ad campaign promised back then.

That’s right – “a guaranteed seat without a reservation,” even if you were the only one on the flight. (That never happened with me and the Missus, for those of you keeping score at home.)

What did happen to us quite often was the weather. In the winter there were snowstorms; in the summer, thunderstorms. One stormy evening our flight to Logan got diverted to Albany, where airline personnel put us on a school bus that had no rest room and a governor on its engine so it couldn’t go above 55 mph. At the Carlton rest stop on the Mass. Pike, the guy sitting in front of us re-boarded with a Big Gulp. You bet that kept us awake the rest of the way home.

More often, though, flights would just be cancelled, leaving us to make a mad dash for the New York Port Authority Bus Terminal in Times Square to catch the next Greyhound to Boston.

The worst was the bus ride when a) I had no reading light, and b) the young gal sitting in front of us reclined her seat all the way back and talked non-stop on her cell phone for the first hour of the trip. I finally leaned forward and said, “Excuse me, miss, but I’m learning far more about your personal life than I’m really comfortable with.”

She gave me her factory-installed OK Boomer look, grumpily signed off with her bestie, and returned her seatback to its full upright position.

I happily slept the rest of the way home.

In 1989 the Eastern shuttle got sold to Donald Trump, who – as Andrew Curran noted at Simple Flying – screwed it up in record time.

The Trump Shuttle operated a fleet of Boeing 727-100s and 727-200s between Boston, New York, and Washington DC. The airline first took to the air in mid-1989. Fourteen months after that first flight, Trump Shuttle defaulted on a $1.1 million debt payment.

Within two years of the first flight, there were active negotiations to sell the airline. By mid-1992, the Trump Shuttle had ceased to exist. It was rebranded, bought by US Airways, and subsequently absorbed into American Airlines.

The Missus and I are lifelong Never Trumpers, so when he took over we switched to the Pan Am shuttle, which Delta bought in 1991. According to Wikipedia, Delta was “the last of the shuttle operations to guarantee a seat to walk-up passengers. If a plane was oversold, a second plane would be rolled out within fifteen minutes to form an ‘extra section’ to fly the overflow passengers. This practice ended in 2005.”

Well before then, however, the Missus and I had stopped flying to New York and started driving there. It was a vastly improved travel experience, not to mention a helluva lot cheaper.

• • • • • • •

Once we arrived in the Big Town, of course, we needed somewhere to stay. Our choice of hotels tended to go in spurts. During the Footwear Era (even I had some shoe clients for a few years), we stayed at the New York Hilton on Sixth – sorry, Avenue of the Americas – at 54th Street. That’s where the Shoe People congregated, so we did too.

Eventually we migrated across Sixth to The Warwick, which was nice but gradually grew less so. During the next five years we mostly stayed at the Club Quarters on West 45th, which was largely affordable because we piggybacked on my brother Bob’s corporate discount.

We also did a nice stretch at The Salisbury on West 57th, which was owned by the next-door Calvary Baptist Church. The rooms were fine, the staff actually remembered us (largely because the Missus is both gracious and generous), and you could get a discount if you attended church services during your stay. The Missus and I never did, for those of you keeping score at home.

(We still have a Salisbury Hotel ballpoint pen, a remnant of that bygone era when amenities like pens and hotel stationery routinely came with your room. Nowadays, you’re lucky if a room comes with your room.)

For a while we ditched hotels for a rental apartment on West 70th off Broadway. It was a clean, airy place up four flights of stairs, which was a bit of a strain. Eventually the place got renovated, which made its new nightly rate even more of a strain, so we moved on. Unfortunately, the next apartment we rented was a Kips Bay flat where someone actually lived between rentals, which turned out to be kind of creepy.

Our final shot at apartment hopping found us in Brooklyn’s Park Slope, that hallowed haven of curated cuisine and bespoke baby strollers. (Don’t ask – we had somehow thought we might one day move back to the city, but we soon came to our senses.) A bigger problem than the terminal tweeness of the neighborhood: It was a 55-minute subway ride to The Met. Game over for any borough but Manhattan.

And so we went back to booking hotel rooms.

The final hotel we landed in was the New York Manhattan on 32nd Street between Fifth and Broadway, in the heart of Koreatown. At first it was a swell place to stay – reasonable rates, comfortable accommodations, elevators a little slow but no big deal. Over time, unfortunately, the bean counters jacked up the rates, removed most of the comforts from the rooms (hey – could we get a chair in here, please?), and generally made it a depressingly bare-bones place to stay.

Then the pandemic came along, and we didn’t stay anywhere in the Big Town.

• • • • • • •

In the Before Times, whenever the Missus and I went to New York – however we got there, wherever we stayed, whatever the reason – all we really cared about was the cultural life of the city. We could easily do and see more in three days than most people we knew would do or see in a week.

Take, for instance, this recap I wrote of a March, 2010 trip the Missus and I took to the city.

WEDNESDAY

Any day that Page One of both the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal features a piece about 17th century Italian painter Caravaggio is bound to be a good art day.

Even in Chelsea.

The Missus and I normally avoid the galleries in that trendoid neighborhood of New York because they’re, well, trendoid. But the current crop of exhibits turned out to be okay.

One Gagosian Gallery in Chelsea had sculptures by Alexander Calder, another had sculptures by David Smith. Pace Wildenstein showcased Joseph Beuys’ anarchic assemblages/sculptures, while Betty Cuningham exhibited William Bailey’s Giorgio Morandiesque still lifes.

One Gagosian Gallery in Chelsea had sculptures by Alexander Calder, another had sculptures by David Smith. Pace Wildenstein showcased Joseph Beuys’ anarchic assemblages/sculptures, while Betty Cuningham exhibited William Bailey’s Giorgio Morandiesque still lifes.

(Sorry, I’m not on this earth long enough to link everything.)

Best of the bunch: the Julie Saul Gallery exhibit of watercolors by Maira Kalman (“a cross between Florine Stettheimer and Milton Avery,” as the Missus rightly noted).

![]() Later on, we caught Remembering Mr. Maugham, a thoroughly engaging two-man play adapted by playwright/director Garson Kanin from his memoir about his lifelong friendship with playwright/novelist/essayist W. Somerset Maugham. It was smart, literate (of course), and at times moving. Our only criticism: It ran for just one week.

Later on, we caught Remembering Mr. Maugham, a thoroughly engaging two-man play adapted by playwright/director Garson Kanin from his memoir about his lifelong friendship with playwright/novelist/essayist W. Somerset Maugham. It was smart, literate (of course), and at times moving. Our only criticism: It ran for just one week.

THURSDAY

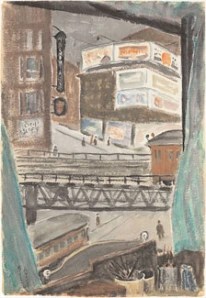

Speaking of Milton Avery, the Knoedler Gallery [shuttered the following year for massive art fraud] currently features Milton Avery: Industrial Revelations through May 1st. It’s a side of Avery the Missus and I had never seen, and apparently we’re not the only ones.

Speaking of Milton Avery, the Knoedler Gallery [shuttered the following year for massive art fraud] currently features Milton Avery: Industrial Revelations through May 1st. It’s a side of Avery the Missus and I had never seen, and apparently we’re not the only ones.

Also worth seeing: Allen Tucker’s portraits and Betty Parsons’ wood constructions at Spanierman, George Segal’s humanoid sculptures at L&M Arts (The Missus: “In black they’re even more lifelike. It’s creepy.”), and the inestimable Man Ray at Zabriske.

On to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where we tagged along on two guided tours: Fashion in Art, which I was allowed to attend with some suspicion, since apparently that daily tour doesn’t get much traffic from the Y-chromosome set; and the daily Modern Art tour, during which we lasted a grand total of three paintings, thanks to our tour guide’s well, let’s just say, eccentricities.

FRIDAY

Start with a quick bang-around of Midtown galleries:

An impressive show of Yvonne Jacquette’s New York urbanscapes at D C Moore, an odd African Americans: Seeing and Seen 1766-1916 exhibit at the Babcock Gallery, Denis Darzaco’s gravity-defying photographs at Laurence Miller, and Seventy Years Grandma Moses at Galerie St. Etienne. Two observations:

An impressive show of Yvonne Jacquette’s New York urbanscapes at D C Moore, an odd African Americans: Seeing and Seen 1766-1916 exhibit at the Babcock Gallery, Denis Darzaco’s gravity-defying photographs at Laurence Miller, and Seventy Years Grandma Moses at Galerie St. Etienne. Two observations:

1) a little Grandma Moses goes a long way;

2) a lot of Grandma Moses went out Galerie St. Etienne’s door: 37 of the 70 painting in the exhibit sold in a little over a month.

Next up: The Approaching Abstraction exhibit at the American Folk Art Museum, which was sort of interesting but not engaging.

And then on to the Museum of Modern Art for Marina Abramovic: The Artist Is Present.

MoMA’s description:

“This performance retrospective traces the prolific career of Marina Abramović (Yugoslav, b. 1946) with approximately fifty works spanning over four decades of her early interventions and sound pieces, video works, installations, photographs, solo performances, and collaborative performances made with Ulay (Uwe Laysiepen). In an endeavor to transmit the presence of the artist and make her historical performances accessible to a larger audience, the exhibition includes the first live re-performances of Abramović’s works by other people ever to be undertaken in a museum setting.”

1946) with approximately fifty works spanning over four decades of her early interventions and sound pieces, video works, installations, photographs, solo performances, and collaborative performances made with Ulay (Uwe Laysiepen). In an endeavor to transmit the presence of the artist and make her historical performances accessible to a larger audience, the exhibition includes the first live re-performances of Abramović’s works by other people ever to be undertaken in a museum setting.”

Loosely translated, this blockbuster performance art retrospective features (not necessarily in this order): nude women standing around, a naked guy lying under a skeleton, a guy with clothes on (!) just lying there with concrete blocks under his head and feet, and endless videos of Abramovic’s history of, yes, nudity, self-mutilation, sexual acts, screaming for no apparent reason, more nudity while hitting herself in the chest with a skull, more random screaming, more random nudity, and etc.

(You can see for yourself here.)

[For those of you keeping score at home, in early 2024 John Bonafede – one of the naked performance artists – sued MoMA, “saying that officials neglected to take corrective action after several visitors groped him during a nude performance for the 2010 retrospective Marina Abramovic: The Artist Is Present,” as Zachary Small reported in the New York Times.]

As a special bonus, the artist herself was appearing in MoMA’s Atrium (as she will throughout the exhibition) in a performance piece that largely consisted of her sitting stone-faced at a table while a succession of people sit across from her, some – wait for it – in various states of nudity. (For a more – I dunno – fleshed-out picture, see this Times review.)

At a certain point the Missus said, “Could we just go look at some real art?” so we went to the permanent galleries to do a little homework on Mark Rothko, since we were going to see [John Logan’s play] Red later on.

But first we swung by the International Center of Photography for Twilight Visions: Surrealism, Photography, and Paris.

But first we swung by the International Center of Photography for Twilight Visions: Surrealism, Photography, and Paris.

From the ICP:

“[P]hotographers such as Jacques-André Boiffard, Brassaï, Ilse Bing, André Kertész, Germaine Krull, Dora Maar, and Man Ray used fragmentation, montage, unusual viewpoints, and various technical manipulations to expose the disjunctive and uncanny aspects of modern urban life.”

On the topic of exposing, the ICP also has an exhibit featuring the “reclusive and mysterious” Czech photographer Miroslav Tichý. “Now over eighty years old, Tichý is a stubbornly eccentric artist, known as much for his makeshift cardboard cameras as for his haunting and distorted images of women and landscapes, many of them taken surreptitiously.”

In other word, a peeper/stalker. Creepy.

A play about Mark Rothko at the height of his artistic powers and fame, Red is a knockout. It takes place in Rothko’s studio mostly in 1949, and there’s lots of talk about abstract expressionism, pop art, and . . . Caravaggio! At one point Rothko (played by the commanding Alfred Molina) waxes eloquent about Caravaggio’s Conversion of Paul, which occupies a dark corner in Rome’s Santa Maria del Popolo and “makes its own light.”

A play about Mark Rothko at the height of his artistic powers and fame, Red is a knockout. It takes place in Rothko’s studio mostly in 1949, and there’s lots of talk about abstract expressionism, pop art, and . . . Caravaggio! At one point Rothko (played by the commanding Alfred Molina) waxes eloquent about Caravaggio’s Conversion of Paul, which occupies a dark corner in Rome’s Santa Maria del Popolo and “makes its own light.”

Just the way Red does.

SATURDAY

One last excursion before heading back home:

One last excursion before heading back home:

A return trip to the Jewish Museum for Alias Man Ray (sadly, just closed).

It was just as good as the first time.

Lively, exhilarating, and typical of trips to the city mapped out by the Missus.

• • • • • • •

We were extremely lucky that we got to see so many major Broadway productions back then, long before it started costing half a month’s rent to catch a show in the Big Town.

Our four decades of theatergoing got off to an auspicious start in 1980 with two amazing musical productions. The first featured Patti LuPone’s transcendent performance in Andrew Lloyd Webber & Tim Rice’s Evita (thank you, Marvelous Marvin Sutton). Here’s how she sounded on her final night in that role.

As one commenter recalled, “I will never forget when she sang this, half the audience was on its feet with tears running down our faces and she too was crying. It was simply extraordinary, beautiful.”

The other production showcased the magical pairing of Angela Lansbury and Len Cariou in Stephen Sondheim’s Sweeney Todd, part of which they reprised during Sondheim’s 75th birthday celebration at the Hollywood Bowl in 2005.

Still tasty after all those years.

P.S. Here’s how the two looked in the original production.

(Full disclosure: I’m pretty sure we saw that production, but the Missus has her doubts, believing we saw the 1982 production with Angela Lansbury and George Hearn, for those of you keeping score at home.)

The ’80s also brought us George C. Scott, Kate Burton, and Nathan Lane in Noël Coward’s Present Laughter; Matthew Broderick in Neil Simon’s Brighton Beach Memoirs; Jeremy Irons, Glenn Close, and Christine Baranski in Tom Stoppard’s The Real Thing; Judd Hirsch and Mercedes Ruehl in Herb Gardner’s I’m Not Rappaport; and Lindsay Duncan and Alan Rickman in a gorgeous production of Christopher Hanson’s Les Liasons Dangereuses. Here they are in a clip from the 1987 Tony Awards (what was presenter Mary Tyler Moore thinking?).

We rounded out the ’80s by catching Madonna’s forgettable performance in David Mamet’s Speed-the-Plow, James Naughton’s memorable one in City of Angels, and Tom Hulce in the 1989 Broadway premiere of Aaron Sorkin’s A Few Good Men. He was superb and should’ve gotten the movie role, but Tom Cruise was bigger box office, so there you go.

We were lucky enough to see Maggie Smith as the hilariously ahistorical docent in Peter Shaffer’s Lettice and Lovage, for which she won the 1990 Tony Award for Best Actress in a Play. Her co-star Margaret Tyzack won Best Featured Actress in a Play. (Here they are at the 1990 Tony Awards.)

The early ’90s brought some other familiar faces to the Broadway stage: Stockard Channing in John Guare’s Six Degrees of Separation and Richard Chamberlain in Alan Jay Lerner’s My Fair Lady (don’t laugh – he was really good).

Also really good: the theatrical offerings in 1994, starting with the great Philip Bosco and Rosemary Harris in J.B. Priestley’s An Inspector Calls. The Missus met Bosco at a charity event some years later, after we had seen him in Michael Frayn’s Copenhagen, an incredibly complex drama about a 1941 meeting between the physicists Niels Bohr and Werner Heisenberg. She told him how terrific we found his performance and asked if he would be doing anything similar soon. He replied that he couldn’t do plays that complicated any more – his memory wasn’t good enough. That was sad, but he was wonderfully kind to the Missus.

Then we bought tickets for Glenn Close’s final performance in Andrew Lloyd Webber/Don Black/Christopher Hampton’s Sunset Boulevard. As the theater lights dimmed, an announcement came over the loudspeaker: “The role of Norma Desmond tonight will be played by . . . [gasps, groans, curses] . . . Glenn Close.” The audience was not amused – and, given the production that ensued, only mildly entertained.

Bebe Neuwirth, on the other hand, was something else in the Broadway revival of George Abbott and Douglas Wallop’s Damn Yankees. The Missus and I had only known her as Frasier Crane’s buttoned-down wife Lilith in the sitcom Cheers. As Lola, she was the polar opposite. (Full disclosure: New York Times critic David Richards liked it a lot less than we did.)

In subsequent years we were fortunate enough to witness many other notable Broadway performances, among them the following . . .

• Marian Seldes in the Vineyard Theatre’s 1994 production of Edward Albee’s Three Tall Women. New York Times critic Ben Brantley called her performance, along with that of Myra Carter, “two of the most riveting performances in town.”

• Philip Bosco and Cherry Jones in Ruth and Augustus Goetz’s The Heiress, the 1995 Tony Award winner for Best Revival of a Play and Best Actress in a Play.

• Zoe Caldwell and Audra McDonald in a masterly production of Terrence McNally’s Master Class, for which they won the 1996 Tony Awards for Best Actress in a Play and Best Featured Actress in a Play. This contemporaneous Reviewer’s Reel will tell you why – especially at the beginning for Caldwell’s acid-tongued Maria Callas, and at 17:54 for McDonald’s spectacular Sharon.

• George Grizzard, Rosemary Harris, and Elaine Stritch in Edward Albee’s A Delicate Balance (1996 Tony Awards: Best Revival of a Play, Best Actor in a Play).

• Al Pacino in Hughie, Eugene O’Neill’s one-act play that was our first Dollar-a-Minute Drama (50 bucks, 50 minutes), though certainly not our last.

• Janet McTeer as a riveting Nora Helmer in Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House, 1997 Tony Award winner for Best Revival of a Play and Best Actress in a Play. (The quality of this video is pretty poor, but the acting is really good.)

• Ann Reinking, Bebe Neuwirth, Joel Grey, and James Naughton in the original Broadway production of Chicago. Here’s Reinking and Naughton (who won the 1997 Tony Award for Best Actor in a Musical; Neuwirth won Best Actress in a Musical) in a rollicking performance of “We Both Reached for the Gun” on the Rosie O’Donnell Show.

• Alan Alda, Victor Garber, and Alfred Molina in a “minimalist, clean and attractively geometric” production of Yazmina Reza’s Art, which won the 1998 Tony Award for Best Play.

• Brian Dennehy and Elizabeth Franz in Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman, 1999 Tony Award winner for best Revival of a Play, Best Actor in a Play, and Best Featured Actress in a Play. (Receipts here.)

• Mary-Louise Parker as a brilliant, haunted math nerd in David Auburn’s Proof, 2000 Tony Award winner for Best Play and Best Actress in a Play.

• Elaine Stritch as very much herself in Elaine Stritch at Liberty, 2002 Tony Award winner for Special Theatrical Event. (Her performance at London’s Old Vic Theatre is here.)

• Lindsay Duncan and Alan Rickman together again – this time in Noël Coward’s Private Lives, 2002 Tony Award winner for Best Revival of a Play and Best Actress in a Play. (Please do your best to ignore the video’s – I dunno, Russian? – subtitles.)

• John Lithgow as J.J. Hunsecker in the Broadway musical version of Sweet Smell of Success, with music by Marvin Hamlisch and book by John Guare. No one can touch Burt Lancaster’s cut-glass turn as the “powerful and sleazy newspaper columnist” in the 1957 movie, but Lithgow did well enough to earn the 2002 Tony Award for Best Actor in a Musical.

• Ashley Judd and Ned Beatty in the 2003 revival of Tennessee Williams’ Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. The play also featured Margo Martindale as Big Mama and Jason Patric as a thoroughly inebriated Brick.

Eight years later Patric delivered an equally soggy performance as the perpetually drunk Tom Daley in the revival of That Championship Season (written by his father Jason Miller), which featured a starry cast of Brian Cox (excellent), Kiefer Sutherland (very good), Jim Gaffigan in his Broadway debut (very impressive), and Chris Noth (very unimpressive).

Fun facts to know and tell: 1) Those were Patric’s only two Broadway performances, and 2) his maternal grandfather was Jackie Gleason. Your punchline goes here.

• Frank Langella, Ray Liotta, and Jane Adams in Stephen Belber’s Match, about which I remember just three things: 1) Ray Liotta didn’t know a bunch of his lines; 2) Jane Adams didn’t know any of hers – she carried a script on stage for the entire performance (to be fair, she’d been parachuted in as a last-minute replacement for the part); and 3) Frank Langella seemed kind of pissed at both of them.

• Cherry Jones and Brian F. O’Byrne in John Patrick Shanley’s Doubt, which won the 2005 Tony Award for Best Play. Jones’s stark portrayal of Sister Aloysius produced both a) shuddering flashbacks to my eight years at St. Ignatius Loyola in the care of the laughingly named Sisters of Charity, and b) the 2005 Tony Award for Best Actress in a Play.

• Kathleen Turner and Bill Irwin in a smashmouth production of Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, which won Irwin a 2005 Tony Award for Best Actor in a Play.

• Christine Ebersole (as “Little” Edie Beale) and Mary Louise Wilson (as Edith Bouvier Beale) in Scott Frankel/Michael Korie/Doug Wright’s Grey Gardens. Here’s Ebersole singing The Revolutionary Costume of Today at the 2007 Tony Awards, where she won Best Actress in a Musical (Wilson won Best Featured Actress in a Musical).

Extremely Edie-fying, wouldn’t you say?

• Julie White as a hilariously scorched-earth Hollywood agent in Douglas Carter Beane’s The Little Dog Laughed, for which she won the 2007 Tony Award for Best Actress in a Play.

• Frank Langella and Michael Sheen in Peter Morgan’s Frost/Nixon, which earned Langella the 2007 Tony Award for Best Actor in a Play.

• Angela Lansbury and Marian Seldes as former tennis partners in Terrence McNally’s Deuce. It was great seeing those two wonderful actresses on stage together.

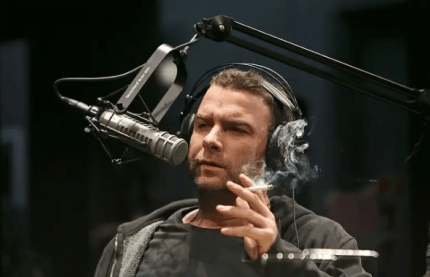

• Liev Schreiber in Eric Bogosian’s Talk Radio. Here’s the lede to Ben Brantley’s review in the New York Times.

Liev Schreiber doesn’t merely fill a stage, as great actors are said to do. In the gut-grabbing revival of Eric Bogosian’s “Talk Radio,” which opened last night at the Longacre Theater, Mr. Schreiber’s presence seems to fill the air as inescapably as weather. You get the feeling that even if you shut your eyes and plugged your ears, he would still be gnawing at your senses and manipulating your mood.

Well, that’s how God is supposed to be, right? Omnipresent, invasive, all-seeing. And Mr. Schreiber is playing Barry Champlain, an abrasive radio talk show host who, as another character puts it, has seen the face of God — “in the mirror.”

In the course of “Talk Radio,” set during one eventful night broadcast in a Cleveland studio, Barry will be forced to confront another, less august image of himself, offered up by the sort of lonely, angry people who regularly phone in. What Barry glimpses allows Mr. Schreiber to provide the most lacerating portrait of a human meltdown this side of a Francis Bacon painting.

No argument here.

• James Gandolfini, Marcia Gay Harden, Jeff Daniels, and Hope Davis in Yasmina Reza’s God of Carnage, which won the 2009 Tony Award for Best Play. As I noted elsewhere at the time, “James Gandolfini very convincingly played not-Tony-Soprano, but Marcia Gay Harden stole the show as his wife,” which won her the 2009 Tony Award for Best Actress in a Play.

• A riveting Jane Fonda as an American musicologist wrestling with both Lou Gehrig’s disease and Beethoven’s genius in Moisés Kaufman’s 33 Variations.

• Janet McTeer (Mary) and Harriet Walter (Elizabeth) in Friedrich Schiller’s Mary Stuart. The Missus and I agreed that both delivered terrific performances, but Walter won the Queen-off.

• Angela Lansbury in Noël Coward’s Blithe Spirit, in which her madcap portrayal of Madame Arcati won her the 2009 Tony Award for Best Featured Actress in a Play.

Remarkably, just a few months later she was back on Broadway in Stephen Sondheim’s A Little Night Music, submitting a touching turn as Madame Armfeldt.

Here’s what I wrote back then: “As we left the theater, the Missus commented that the musical emphasized the raunchy elements at the expense of the lyrical and tender ones, and I entirely agree. Meanwhile, Catherine Zeta-Jones did a bit of scenery-chewing in her role as Desirée Armfeldt, but at least she didn’t have to floss between scenes.”

Full disclosure: Zeta-Jones won the 2010 Tony Award for Best Actress in a Musical Play, so what do I know.

• Liev Schreiber and Scarlett Johansson in Arthur Miller’s A View From the Bridge. He was compelling as Eddie Carbone and she was even better as the niece he burned for, winning the 2010 Tony Award for Best Featured Actress in a Play.

• Laura Linney and Eric Bogosian in Donald Margulies’ Time Stands Still, a meditation on journalism and war and loss and compromise.

And that brought us to 2011.

• • • • • • •

(What follows is a Whitman’s sampler of what the Missus and I caught during our many trips to the city between 2011 and 2014, along with links to my recaps when we got back home.)

In the summer of 2011, the Big Exhibit in the Big Town was Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The exhibition, organized by The Costume Institute, celebrates the late Alexander McQueen’s extraordinary contributions to fashion. From his Central Saint Martins postgraduate collection of 1992 to his final runway presentation, which took place after his death in February 2010, Mr. McQueen challenged and expanded the understanding of fashion beyond utility to a conceptual expression of culture, politics, and identity. His iconic designs constitute the work of an artist whose medium of expression was fashion. The exhibition features approximately one hundred ensembles and seventy accessories from Mr. McQueen’s prolific nineteen-year career.

It was an eye-popping tribute to the unique vision of a fashion designer who cut his dresses long but his life short at the age of 40. Very sad, indeed.

Ten blocks north at the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum, Set in Style: The Jewelry of Van Cleef & Arpels was on glittering display. Here’s a gallery tour with installation designer Patrick Jouin.

At the time I called it “one giant product placement (literally) for the upscale jeweler.” New York Times critic Karen Rosenberg was far less gentle.

“The recipe for making an exquisite piece of jewelry is akin to haute cuisine: masters employ special techniques to mix and adorn top-quality ingredients, creating something that is far greater than the sum of its parts.” So says the unctuous wall text introducing “Set in Style: The Jewelry of Van Cleef & Arpels,” a banquet of the most distasteful variety at the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum.

National Design Museum.

Van Cleef & Arpels, the century-old French jewelry firm, is the show’s primary sponsor and has supplied much of its megacarat menu: some 350 lavish pieces worn by royals, screen sirens and social swans.

The extravagance isn’t the nauseous part; staggering displays of wealth don’t look out of place in this former Carnegie mansion. But allowing a luxury brand that’s still very much in existence to bankroll its own exhibition — one that often looks as if it were put together by the company’s creative directors — does not seem like a smart move, even if it draws A-listers to the opening-night gala.

Ouch.

Far better was Color Moves: Art and Fashion by Sonia Delaunay, a collection of the under-appreciated artist’s textile and fashion designs. New York Times critic Roberta Smith called it “a sumptuous and enlightening show . . . that may change forever the way you look at dry goods.”

Fabric samples:

That might have been the last Cooper-Hewitt exhibit the Missus and I truly enjoyed. Soon after, the museum went full-tilt high tech in both the subjects and the presentation of its exhibits. Here’s how contributing writer Jimmy Stamp described the latter in a 2014 Smithsonian Magazine piece.

Throughout the museum, a series of new interactive features enhance the experience of every exhibition. Foremost among them is The Pen . . . a digital stylus given to every visitor to help them interact with the objects on display. Here’s how it works: every wall label includes a small cross symbol and an identical symbol is on the top of The Pen—when the two are pressed together, The Pen vibrates to signal the interaction, and the object is saved to your personal online collection, which is keyed to either your ticket or a unique user profile.

End result: That “alternative to passive audio guides” had people of all ages dashing hither and thither to randomly joy-stick wall labels at exhibits like Access+Ability (“Fueled by advances in research, technology, and fabrication, this proliferation of functional, life-enhancing products is creating unprecedented access in homes, schools, workplaces, and the world at large”) or The Senses: Design Beyond Vision (“Explore experimental works and practical solutions designed to inspire wonder and new ways of accessing our world”).

The Missus and I guessed that most people were unlikely to look even once at the objects in their feverishly assembled “personal online collection,” which meant they’d never see the objects at all.

We’d already realized that the days of pop-up book and mustard pot exhibits were long gone, but the new Cooper-Hewitt increasingly just seemed to me a cross between pretentious and sad.

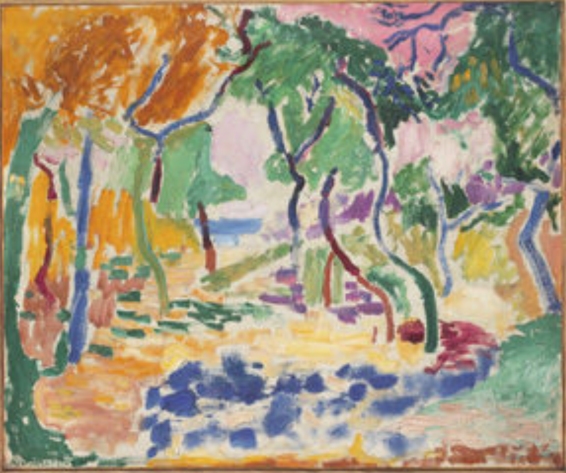

A couple more blocks north, the Jewish Museum featured Collecting Matisse and Modern Masters: The Cone Sisters of Baltimore. That would be Claribel and Etta Cone, who collected about 3000 decorative objects and works of art from the likes of Pierre Bonnard, André Derain, and especially Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse.

For those of you keeping score at home: Etta Cone (at right, below) was in love with Gertrude Stein (at center, below), but got aced out by Alice B. Toklas. So Etta didn’t collect everything she’d hoped to.

Henri Matisse fondly called Dr. Claribel and Miss Etta Cone “my two Baltimore ladies.” The two Cone sisters began buying art directly out of the Parisian studios of avant-garde artists in 1905. Although the sisters’ taste for modern art was little understood—critics disparaged Matisse at the time and Pablo Picasso was virtually unknown—the Cones followed their passions and amassed one of the world’s greatest art collections including artworks by Matisse, Picasso, Paul Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh, Paul Cézanne, and other modern masters . . .

Collecting Matisse and Modern Masters: The Cone Sisters of Baltimore features over 50 of these works of art—including paintings, sculptures and works on paper by Matisse, Picasso, Gauguin, Renoir, van Gogh, Pissarro, Courbet and more—on loan from The Baltimore Museum of Art.

Paging Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, and Paul Gauguin . . .

Here’s a virtual tour of the Cone sisters’ Baltimore apartments, via the Imaging Research Center. It’s a corker.

Bonus Flâneur Double Feature: 1) A gallery tour of the Baltimore Museum of Art’s Cone Collection, and 2) Michael Palin’s 2003 BBC documentary, The Ladies Who Loved Matisse.

• • • • • • •

In January of 2012 we were back in the Big Town for a quick art-go-round, starting with Vivian Maier: Photographs From the Maloof Collection at Howard Greenberg Gallery.

A nanny by trade, Vivian Maier’s street and travel photography was discovered by John Maloof in 2007 at a local auction house in Chicago. Always with a Rolleiflex around her neck, she managed to amass more than 2,000 rolls of films, 3,000 prints and more than 100,000 negative which were shared with virtually no one in her lifetime. Her black and white photographs–mostly from the 50s and 60s–are indelible images of the architecture and street life of Chicago and New York. She rarely took more than one frame of each image and concentrated on children, women, the elderly, and indigent.

Maier also produced “a series of striking self-portraits” like this one.

Much more of Maier’s work here – all well worth a look.

Next stop was the Bard Graduate Center to catch Hats: An Anthology by Stephen Jones, which originated at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum.

The exhibition, which had over 100,000 visitors at the V&A, displays more than 250 hats chosen with the expert eye of a milliner.

On display are hats ranging from a twelfth-century Egyptian fez to a 1950s Balenciaga hat and couture creations by Jones and his contemporaries. To show the universal appeal of wearing hats, Jones has chosen wide variety of styles such as motorcycle helmets, turbans, berets, and a child’s plastic tiara. There also are hats worn by Madonna and Keira Knightley. For the special exhibition at the BGC, the curators have arranged for loans found only in the United States, including Babe Ruth’s baseball cap, original 1950s Mouseketeer ears, and the top hat worn by President Franklin Roosevelt to his fourth inauguration.

Hat damn!

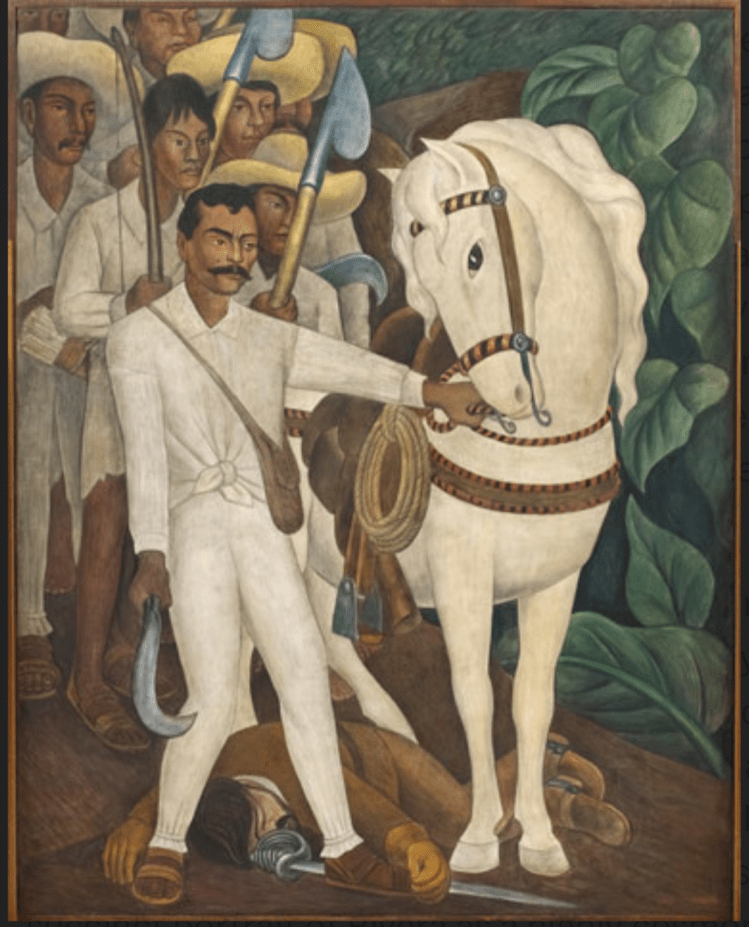

Damn – or language even stronger than that – was the byword between Diego Rivera and the Rockefeller family when John D. Jr. hired the Mexican artist in 1932 to create a mural for the new Rockefeller Center across Fifth Avenue from St. Patrick’s Cathedral.

Diego Rivera: Murals for The Museum of Modern Art provided the backdrop.

Diego Rivera was the subject of MoMA’s second monographic exhibition (the first was Henri Matisse), which set new attendance records in its five-week run from December 22, 1931, to January 27, 1932. MoMA brought Rivera to New York six weeks before the exhibition’s  opening and gave him studio space within the Museum, a strategy intended to solve the problem of how to present the work of this famous muralist when murals were by definition made and fixed on site. Working around the clock with two assistants, Rivera produced five “portable murals”—large blocks of frescoed plaster, slaked lime, and wood that feature bold images drawn from Mexican subject matter and address themes of revolution and class inequity. After the opening, to great publicity, Rivera added three more murals, now taking on New York subjects through monumental images of the urban working class and the social stratification of the city during the Great Depression. All eight were on display for the rest of the show’s run. The first of these panels, Agrarian Leader Zapata, is an icon in the Museum’s collection.

opening and gave him studio space within the Museum, a strategy intended to solve the problem of how to present the work of this famous muralist when murals were by definition made and fixed on site. Working around the clock with two assistants, Rivera produced five “portable murals”—large blocks of frescoed plaster, slaked lime, and wood that feature bold images drawn from Mexican subject matter and address themes of revolution and class inequity. After the opening, to great publicity, Rivera added three more murals, now taking on New York subjects through monumental images of the urban working class and the social stratification of the city during the Great Depression. All eight were on display for the rest of the show’s run. The first of these panels, Agrarian Leader Zapata, is an icon in the Museum’s collection.

As for that Rocky commission, here’s how MoMA’s press release described it.

While Rivera was in New York in 1931, he began discussions for a commission at Rockefeller Center. Materials related to the commission are on view, including preparatory drawings for the Rockefeller mural, Man at the Crossroads, and photographs of the mural in progress . . . Rivera began work on the mural in March 1933, but by mid-May he had been discharged from the project and his fresco covered with a tarp, concealed until it was chipped from the wall the following year. The most frequently cited reason for the sudden dismissal of the artist is Rivera’s inclusion of a portrait of Vladimir Lenin – a detail that provoked inflammatory headlines. Rivera’s patrons requested that he remove the offending image, but he refused.

Far more offensive than the portrait of Lenin, however, was the image alongside him of Junior “drinking martinis with a harlot” (lots more juicy details in this NPR piece by Allison Keyes).

Undeterred – or perhaps spurred – by the destruction of the original mural, Rivera recreated this version, named Man, Controller of the Universe.

At least Diego Rivera could control that.

The next day we were back on the photography beat with Cecil Beaton: The New York Years at the Museum of the City of New York. Here’s how Leslie Camhi began her review it in the New York Times.

What was Manhattan for the wildly ambitious, talented and tirelessly self-promoting 24-year-old Cecil Beaton, but a candy box of opportunities, just waiting to be picked? And pick them he did, over the course of some five decades, in a peripatetic career that saw him cross-pollinating the social and cultural elites of the Old and New Worlds, and applying his protean gifts to everything from fashion photography and portraiture to illustration to stage and costume design. “Cecil Beaton: The New York Years,”curated by Donald Albrecht and opening today at the Museum of the City of New York, includes vintage fashion prints and a wide range of portraits, from Marilyn Monroe (cajoled into relaxation in Beaton’s Ambassador Hotel suite) to the very young Mick Jagger to Wallis Simpson and the aging Greta Garbo (one of the photographer’s rare heterosexual liaisons). Together with drawings, theatrical designs and other ephemera, they illuminate this English dandy’s astonishingly productive and long-lasting engagement with the booming cultural metropolis that was Manhattan at midcentury.

That’s Andy Warhol and Candy Darling in a 1969 photo, in case you were wondering.

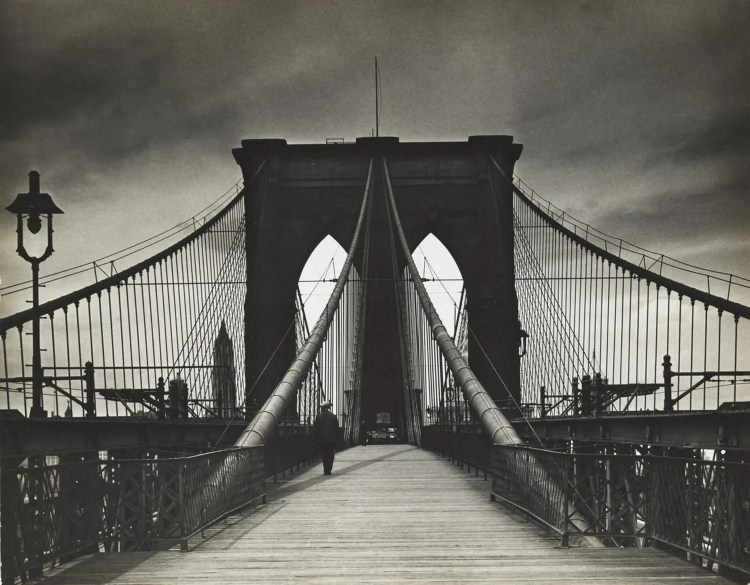

Continuing to keep tabs on the shutterbug set, we dropped down to the Jewish Museum to take in The Radical Camera: New York’s Photo League, 1936-1951.

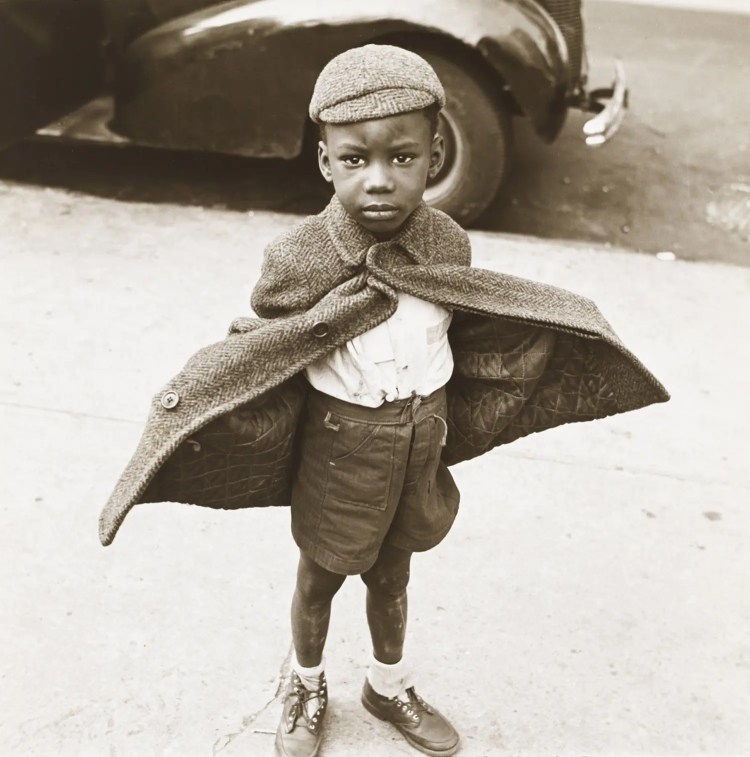

Artists in the Photo League were known for capturing sharply revealing, compelling moments from everyday life. Their focus centered on New York City and its vibrant streets — a shoeshine boy, a brass band on a bustling corner, a crowded beach at Coney Island. Many of the images are beautiful, yet harbor strong social commentary on issues of class, child labor, and opportunity. The Radical Camera explores the fascinating blend of aesthetics and social activism at the heart of the Photo League.

This review in Time magazine offers a nice array of Photo League images, from Alexander Alland’s 1938 Untitled (Brooklyn Bridge) . . .

to Jerome Liebling’s classic Butterfly Boy, New York (1949) . . .

to Berenice Abbott’s Zito’s Bakery, 259 Bleecker Street (1937).

Great show.

Our last stop was Maurizio Cattelan: All at the Guggenheim Museum, and it was all that and more.

The exhibition brings together virtually everything the artist has produced since 1989 and presents the works en masse, strung seemingly haphazardly from the oculus of the Guggenheim’s rotunda. Perversely encapsulating Cattelan’s career to date in an overly literal, three-dimensional catalogue raisonné, the installation lampoons the idea of comprehensiveness. The exhibition is an exercise in disrespect: the artist has hung up his work like laundry to dry.

Alternative take: This nutshell review of the exhibit I posted on Campaign Outsider that night.

Common elements in this exhibit: Lots of taxidermy (dogs, pigeons, horses, donkeys), lots of suicide (even a squirrel suicide in a little kitchen), lots of historical figures (Picasso, Hitler, Pope John Paul II killed by a meteor).

Also: Granny in the fridge, the world’s largest foosball table, and a whole bunch of stuff the hardworking staff isn’t smart enough to understand.

But two things we do know:

1) It wasn’t enough for the museum goers (and this was on Pay What You Wish Night) to just look at the the truly amazing array of artwork. Shutterbug Nation needs to RECORD it on their Smartphones.

2) Maurizio Cattelan has got issues.

The Missus and I, by contrast, had no issues at all as we happily trundled home.

• • • • • • •

As it turned out, 2012 was also a very good theatergoing year for me and the Missus. On a trip to the city in March, we went down to the Barrow Street Theatre in Greenwich Village to see Nina Raine’s Tribes, which New York Times critic Ben Brantley called “a smart, lively and beautifully acted new play that asks us to hear how we hear, in silence as well as in speech.”

This British-born comic drama . . . considers the passive and aggressive forms of listening (or not listening) within an insular intellectual family. They’re a bunch of dueling narcissists, this lot, with words as their weapons of choice.

You’ve probably met their kind before in fiction (like J. D. Salinger’s tales of the Glass family) or film (like Wes Anderson’s “Royal Tenenbaums”). But a few significant traits set Ms. Raine’s characters apart from similar clans with high I.Q.’s and a self-regard to match. One of their members, you see, is deaf. Everyone else more or less pretends that he is not. And therein lie the seeds of a rebellion that could crack a house in two.

The performance we saw pretty much brought the house down.

Much the same happened at the Broadway revival of Gore Vidal’s The Best Man, which featured a star-studded cast of Candice Bergen, James Earl Jones, John Larroquette, Eric McCormack, and – God love her – Angela Lansbury. Here’s her first scene.

The Missus and I felt very lucky to have seen that wonderful actress in so many notable performances.

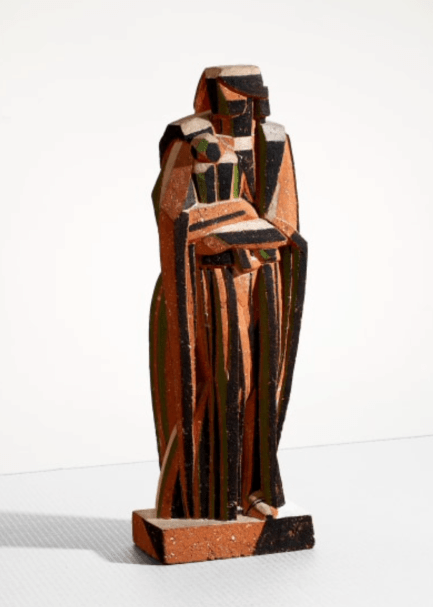

A couple of months later we were back in the Big Town cruising various gallery shows. One of the most compelling was The Figure in Modern Sculpture at the Forum Gallery, which featured works by Alexander Archipenko, Chaim Gross, Gaston Lachaise, Jacques Lipchitz, Elie Nadelman, and John Storrs.

From the Forum Gallery’s press release: “[B]eginning with the second decade of the twentieth century, artists on both sides of the Atlantic broke with academic tradition to depict modern man in original ways, infusing their work with a sense of mystery, mirth and movement, creating a new and dynamic vision of the human figure.”

Representative samples . . .

Then it was on to Gagosian’s Madison Avenue gallery for Picasso and Françoise Gilot: Paris–Vallauris 1943–1953.

This exhibition is a departure from its precedents in that it has been conceived as a visual and conceptual dialogue between the art of Picasso and the art of Françoise Gilot, his young muse and lover during the period of 1943 to 1953. The result of an active collaboration between Gilot and Picasso’s biographer John Richardson, assisted by Gagosian director Valentina Castellani, Picasso and Françoise Gilot celebrates the full breadth and energy of Picasso’s innovations during these postwar years, presenting Gilot’s paintings alongside his marvelously innovative depictions of her and their family life. It is the first time that their work has been exhibited together—that the painterly dialogue between the fascinated mature male artist and the self-possessed young female artist can be retraced and explored.

Picasso on Gilot . . .

Gilot on Picasso . . .

You get the picture.

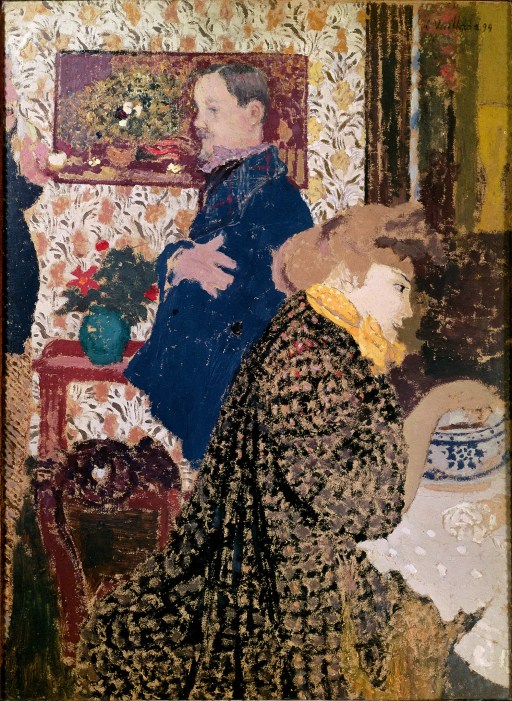

Another smart show was Edouard Vuillard: Paintings And Works On Paper at Jill Newhouse Gallery.

“On February 13, 1923, now more than ninety years ago, Vuillard dropped by the Hotel Meurice, where his old friend, Misia, was finishing a long lunch with Coco Chanel and Pierre Bonnard. It seems that Bonnard walked Vuillard back to the apartment Misia shared with her third husband, the Catalan painter, Josep Maria Sert. From Vuillard’s brief journal entry, we know that Sert insisted then and there that Vuillard paint a portrait of Misia, which the painter commenced—seemingly against his will—in 1923…… “

The resulting painting titled The Black Cups was called by Musée d’Orsay Director and Vuillard scholar Guy Cogeval a “perverse anti-portrait.” This painting, a large preparatory study in distemper, and 113 preparatory drawings, will be exhibited together for the first time, in a highly focused exhibition designed to complement the much larger retrospective of Vuillard’s career at the Jewish Museum in New York.

The Missus and I are a sucker for retrospectives, so we moseyed up to the Jewish Museum to catch Edouard Vuillard: A Painter and His Muses, 1890-1940.

As a young man in the 1890s, Vuillard was a member of a Parisian group of avant-garde artists known as the Nabis (“prophets” in Hebrew and Arabic). Taking their inspiration from the Post-Impressionist Paul Gauguin, the group used simplified form and pure colors to create decorative, emotionally charged pictures. During his Nabi period, Vuillard produced some of his best-known artworks: paintings of friends and family in warm interiors filled with patterned wallpapers, draperies, carpets, and clothing

As a young man in the 1890s, Vuillard was a member of a Parisian group of avant-garde artists known as the Nabis (“prophets” in Hebrew and Arabic). Taking their inspiration from the Post-Impressionist Paul Gauguin, the group used simplified form and pure colors to create decorative, emotionally charged pictures. During his Nabi period, Vuillard produced some of his best-known artworks: paintings of friends and family in warm interiors filled with patterned wallpapers, draperies, carpets, and clothing

As New York Times art critic Ken Johnson noted at the time in a helpful overview of Vuillard’s career, “before the age of 30 he made some of the most beguiling paintings of fin de siècle Paris . . . Painting with special attention to wallpaper and fabric patterns, he made people almost dissolve into atomized, flattened surfaces, anticipating a century that would pulverize into air everything once taken for solid.”

Case in point: this depiction of Félix Vallotton and Misia Natanson in the Natansons’ dining room at Rue Saint-Florentin.

After 1900, Johnson wrote, “Vuillard . . . turned back his own clock. Reverting to a more conventionally naturalistic style and often using his own photographs as references, he painted portraits of well-to-do people and decorative murals for their homes. In the eyes of many critics he became a mere society painter.” The two Vuillard exhibits, however, illustrated that he was “not just another John Singer Sargent knocking out suave portraits of the rich and indolent for lunch money,” as Johnson put it, but deeper and more rewarding than that.

Ten blocks down Fifth Avenue, the Metropolitan Museum of Art hosted The Steins Collect: Matisse, Picasso, and the Parisian Avant-Garde, a sweeping survey of a remarkable family’s remarkable art collection.

Gertrude Stein, her brothers Leo and Michael, and Michael’s wife Sarah were important patrons of modern art in Paris during the first decades of the twentieth century. This exhibition unites some two hundred works of art to demonstrate the significant impact the Steins’ patronage had on the artists of their day and the way in which the family disseminated a new standard of taste for modern art . . .

Beginning with the art that Leo Stein collected when he arrived in Paris in 1903—including paintings and prints by Paul Cézanne, Edgar Degas, Paul Gauguin, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Édouard Manet, and Auguste Renoir—the exhibition traces the evolution of the Steins’ taste and examines the close relationships formed between individual members of the family and their artist friends. While focusing on works by Matisse and Picasso, the exhibition also includes paintings, sculpture, and works on paper by Pierre Bonnard, Maurice Denis, Juan Gris, Marie Laurencin, Jacques Lipchitz, Henri Manguin, André Masson, Elie Nadelman, Francis Picabia, and others.

More pictures from the exhibition here.

As I noted at the time, the Missus and I checked out one other exhibit, which was distinguished largely by the crowd it drew.

Schiaparelli and Prada: Impossible Conversations, while hosting the most pretentious gathering of humans per square foot in the universe, still delivered a smart compare-and-contrast of two fashion giants.

Our theater karma stayed strong on that trip, starting with Jon Robin Baitz’s Other Desert Cities, which featured Stockard Channing, Judith Light, Stacy Keach, Thomas Sadoski, and Elizabeth Marvel – all of them marvelous.

We also caught Paul Weitz’s Lonely, I’m Not with Topher Grace and Olivia Thirlby. Nutshell review from the Missus: “A totally charming, clever production that was just SO CUTE.”

Last but not least: Gina Gionfriddo’s Rapture, Blister, Burn with Amy Brenneman and Kellie Overby, a “comedy-drama about the fallout of choices made by two women of the generation that followed the modern women’s movement.” New York Times critic Charles Isherwood called it “intensely smart [and] immensely funny.” We totally agreed.

• • • • • • •

The Missus and I went back to the Big Town at Christmastime and caught a preview performance of the Broadway revival of Picnic, William Inge’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play. Here’s what I wrote afterward.

We liked it a lot, despite lead actor Sebastian Stan’s chewing enough scenery that he needs to floss after every performance.

(Then again, as the Missus noted, William Holden did much the same in the 1955 movie version.)

But Ellen Burstyn and Mare Winningham are terrific in the new production, as was Elizabeth Marvel, whose performance as Rosemary Sydney eerily echoes Rosalind Russell’s in the film.

Even better, the Missus met some lovely women from Long Island who invited her to join their weekly Mah Jong game.

Ah! To live in the Big Town!

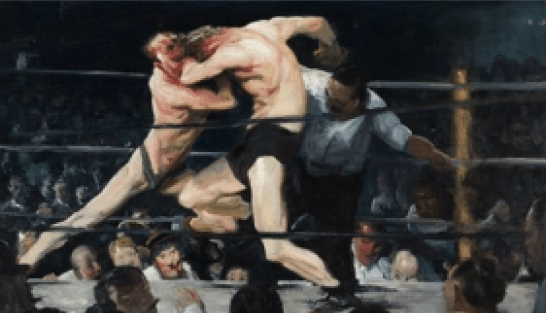

We spent most of the next day at The Met and saw, among other exhibits, George Bellows.

George Bellows (1882–1925) was regarded as one of America’s greatest artists when he died, at the age of forty-two, from a ruptured appendix. Bellows’s early fame rested on his powerful depictions of boxing matches and gritty scenes of New York City’s tenement life, but he also painted cityscapes, seascapes, war scenes, and portraits, and made illustrations and lithographs that addressed many of the social, political, and cultural issues of the day.

Coincidentally, that night we went to the Lincoln Center revival of Golden Boy, the Clifford Odets classic (that, also coincidentally, featured William Holden in the 1939 film version). The entire cast was excellent, especially Tony Shaloub as Mr. Bonaparte (lots more clips here).

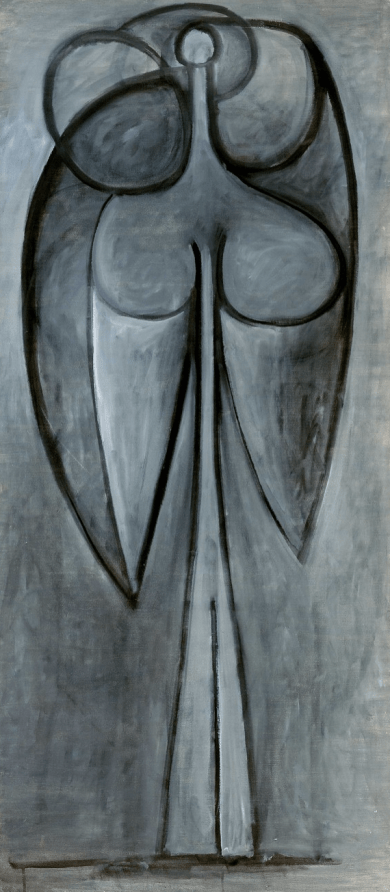

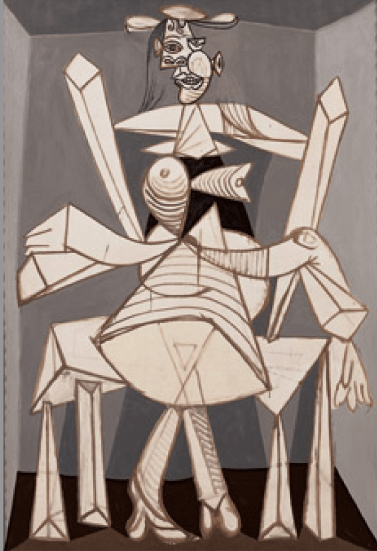

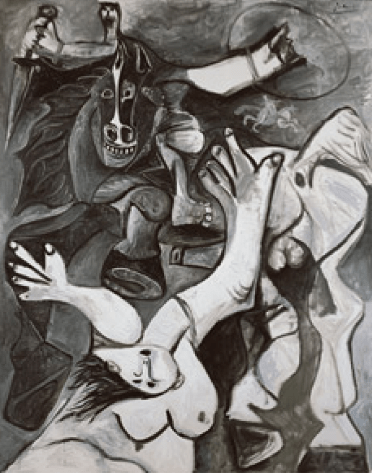

The next day we moseyed up to the Guggenheim for Picasso Black and White.

Picasso Black and White is the first exhibition to explore the remarkable use of black and white throughout the Spanish artist’s prolific career. Claiming that color weakens, Pablo Picasso purged it from his work in order to highlight the formal structure and autonomy of form inherent in his art. His repeated minimal palette correlates to his obsessive interest in line and form, drawing, and monochromatic and tonal values, while developing a complex language of pictorial and sculptural signs. The recurrent motif of black, white, and gray is evident in his Blue and Rose periods, pioneering investigations into Cubism, neoclassical figurative paintings, and retorts to Surrealism. Even in his later works that depict the atrocities of war, allegorical still lifes, vivid interpretations of art-historical masterpieces, and his sensual canvases created during his twilight years, he continued to apply a reduction of color.

Picasso purged it from his work in order to highlight the formal structure and autonomy of form inherent in his art. His repeated minimal palette correlates to his obsessive interest in line and form, drawing, and monochromatic and tonal values, while developing a complex language of pictorial and sculptural signs. The recurrent motif of black, white, and gray is evident in his Blue and Rose periods, pioneering investigations into Cubism, neoclassical figurative paintings, and retorts to Surrealism. Even in his later works that depict the atrocities of war, allegorical still lifes, vivid interpretations of art-historical masterpieces, and his sensual canvases created during his twilight years, he continued to apply a reduction of color.

Among the exhibit’s artworks were these.

As I wrote back then, it’s like Picasso dismantled the human body and then reassembled it without consulting the owner’s manual.

On the way back to Boston we stopped by the Yale University Art Gallery to see its spectacular installation, The Société Anonyme: Modernism for America.

The Société Anonyme Collection at the Yale University Art Gallery is an exceptional anthology of European and American art in the early 20th century. Founded in New York in 1920 by Katherine S. Dreier, Marcel Duchamp, and Man Ray to promote contemporary art among American audiences, Société Anonyme, Inc., was an experimental museum dedicated to the idea that the story of modern art should be told by artists. The Société Anonyme: Modernism for America traces the transformation of this organization from an exhibition initiative to an extraordinary art collection. It features works by over 100 artists who made significant contributions to modernism, including Constantin Brancusi, Paul Klee, Piet Mondrian, and Joseph Stella, along with lesser-known artists, such as Marthe Donas, Louis Eilshemius, and Angelika Hoerle.

The Société Anonyme Collection at the Yale University Art Gallery is an exceptional anthology of European and American art in the early 20th century. Founded in New York in 1920 by Katherine S. Dreier, Marcel Duchamp, and Man Ray to promote contemporary art among American audiences, Société Anonyme, Inc., was an experimental museum dedicated to the idea that the story of modern art should be told by artists. The Société Anonyme: Modernism for America traces the transformation of this organization from an exhibition initiative to an extraordinary art collection. It features works by over 100 artists who made significant contributions to modernism, including Constantin Brancusi, Paul Klee, Piet Mondrian, and Joseph Stella, along with lesser-known artists, such as Marthe Donas, Louis Eilshemius, and Angelika Hoerle.

Representative samples from Kurt Schwitters, Man Ray, and Katherine Dreier.

New York Times critic Martha Schwendener noted one legacy of the Société Anonyme: “It suggested a version of modernism different to that highlighted, as Dreier put it, in ‘most collections.’ (By 1936 she felt there was ‘neither love nor intelligence regarding art’ over at MoMA.)”

We’ll let MoMA rebut in good time.

• • • • • • •

In November of 2013, there were two highlights in the Big Town. First, The Line King’s Library at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center, “the largest exhibition of Al Hirschfeld’s artwork and archival material from its collection.”

Al Hirschfeld (1903 – 2003) brought a new set of visual conventions to the task of performance portraiture when he made his debut in 1926. His signature work, defined by a linear calligraphic style, made his name a verb: to be “Hirschfelded” was a sign that one has arrived. Hirschfeld said his contribution was to take the character, created by the playwright and portrayed by the actor, and reinvent it for the reader. Playwright Terrence McNally wrote: “No one ‘writes’ more accurately of the performing arts than Al Hirschfeld. He accomplishes on a blank page with his pen and ink in a few strokes what many of us need a lifetime of words to say.”

As Naomi Fry noted in a New Yorker piece two years ago, “in the course of his nearly nine-decade career, [Hirschfeld] captured the likenesses of a wide-ranging array of performers in the world of theatre, music, television, and film: from Leonard Bernstein to Liza Minnelli, Dizzy Gillespie to the “Sex and the City” foursome, the Beatles to the “Sesame Street” puppets, Katharine Hepburn to Cher.”

This fabulous New York Times documentary (via some Russian (?) outfit called Bkk) tells you all you need to know.

About a mile uptown, the New-York Historical Society had mounted The Armory Show at 100, “an exhibition of more than ninety masterworks from the 1913 exhibition, including the European avant-garde, icons of American art, and earlier works that were meant to show the progression of modern art.”

The Armory Show was a stunning exhibition of nearly 1,400 objects that included both  American and European works, but it is best known for introducing the American public to the new in art: European avant-garde paintings and sculpture. One hundred years later it is hard to imagine what it would have been like to see works by Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Marcel Duchamp, Paul Gauguin, Paul Cézanne, and Vincent Van Gogh, all together for the very first time. The exhibition created a huge sensation in New York. It traveled to Chicago and Boston, and was even more controversial in Chicago, where students burned paintings by Matisse in effigy. The exhibition’s travel turned it into a national event, and the polemical responses to the show have come to represent a turning point in the history of American art.

American and European works, but it is best known for introducing the American public to the new in art: European avant-garde paintings and sculpture. One hundred years later it is hard to imagine what it would have been like to see works by Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Marcel Duchamp, Paul Gauguin, Paul Cézanne, and Vincent Van Gogh, all together for the very first time. The exhibition created a huge sensation in New York. It traveled to Chicago and Boston, and was even more controversial in Chicago, where students burned paintings by Matisse in effigy. The exhibition’s travel turned it into a national event, and the polemical responses to the show have come to represent a turning point in the history of American art.

There’s a ton of 1913 Armory Show artworks here, but spoiler alert: The European stuff is amazing, the American stuff much less so.

• • • • • • •

When we returned to the Big Town the following June, we went hither and yon to catch a batch of museum exhibits and gallery shows.

• The American Folk Art Museum for Self-Taught Genius: Treasures from the American Folk Art Museum. It was . . . smart.

• The Museum of Art and Design (whose offerings I quite often didn’t get) for Re:Collection and Multiple Exposures: Jewelry and Photography. They were, well, smarter than I was.

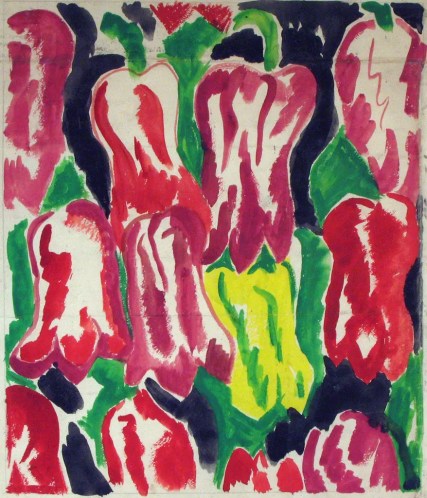

• The Museum of Modern Art to see Gauguin: Metamorphoses, which was kind of meh. Then again, we’ve always thought Gauguin was a one-trick painter.

But we did like MoMA’s Lygia Clark: The Abandonment of Art, 1948–1988.

• The New-York Historical Society for Bill Cunningham: Facades and The Black Fives, which “[covered] the pioneering history of the African-American basketball teams that existed in New York City and elsewhere from the early 1900s through 1950, the year the National Basketball Association became racially integrated.”

Jordan G. Teicher’s review in Slate has lots of photos, including this one of the 1943 Washington Bears professional basketball team.

• The Jewish Museum for Masterpieces and Curiosities: Diane Arbus’s Jewish Giant. It was, well, smaller than that.

• The Met to catch Charles James: Beyond Fashion, an exhibit celebrating the “wildly idiosyncratic, emotionally fraught fashion genius.” And yes he was.

• Finally, pay-what-you-wish-night ($22 admission fee? seriously?) at the Guggenheim for Italian Futurism, 1909–1944: Reconstructing the Universe. Even more seriously, admission is now $30.

We also managed to get to the theater one night to see Act One at Lincoln Center, a play by James Lapine based on Broadway legend Moss Hart’s autobiography, which Frank Rich called “The greatest showbiz book ever written” in an article in New York Magazine.

At the time I said it “was kind of hokey but featured terrific performances in multiple roles by Tony Shaloub and Andrea Martin.” Here’s a taste.

That was the final act for that trip.

• • • • • • •

Six months later, the Big Town was a regular Pablo-palooza. Start with Picasso & the Camera at the Gagosian Gallery in Chelsea, a stunning display that “explores how Picasso used photography not only as a source of inspiration, but as an integral part of his studio practice.”

Pace Gallery Midtown and Pace Gallery Chelsea offered Picasso & Jacqueline: The Evolution of Style, “featuring nearly 140 works by Pablo Picasso created in the last two decades of his life while living with his muse, and later, wife, Jacqueline Roque.”

Special bonus: MARISOL: Sculptures and Works on Paper at El Museo del Barrio offered this Picasso sculpture.

Gagosian/Pace/Del Barrio: That’s Picasso cubed, for those of you keeping score at home.

Coincidentally, Cubism: The Leonard A. Lauder Collection was on exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, a show that kind of made your head explode for a couple of reasons: 1) it featured 81 different Cubist works; and 2) they all belonged to one guy.

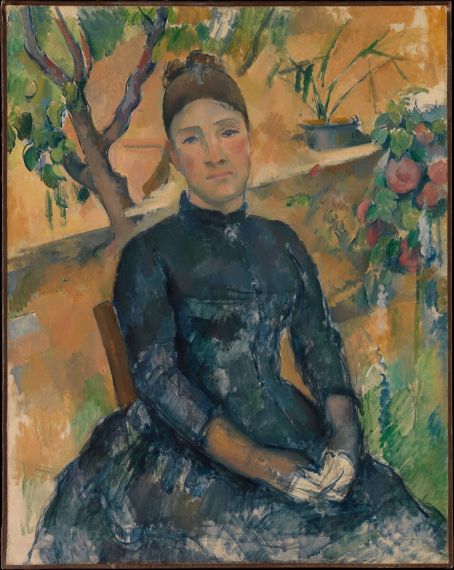

Also at The Met was the thoroughly compelling Madame Cézanne exhibit.

This exhibition of paintings, drawings, and watercolors by Paul Cézanne (French, 1839–1906) traces his lifelong attachment to Hortense Fiquet (French, 1850–1922), his wife, the mother of his only son, and his most-painted model. Featuring twenty-five of the artist’s twenty-nine known portraits of Hortense, including Madame Cézanne in the Conservatory (1891) and Madame Cézanne in a Red Dress (1888–90), both from the Metropolitan Museum’s collection, the exhibition explores the profound impact she had on Cézanne’s portrait practice.

his only son, and his most-painted model. Featuring twenty-five of the artist’s twenty-nine known portraits of Hortense, including Madame Cézanne in the Conservatory (1891) and Madame Cézanne in a Red Dress (1888–90), both from the Metropolitan Museum’s collection, the exhibition explores the profound impact she had on Cézanne’s portrait practice.

The works on view were painted over a period of more than twenty years, but despite this long liaison, Hortense Fiquet’s prevailing presence is often disregarded and frequently diminished in the narrative of Cézanne’s life and work. Her expression in the painted portraits has been variously described as remote, inscrutable, dismissive, and even surly. And yet the portraits are at once alluring and confounding, recording a complex working dialogue that this unprecedented exhibition and accompanying publication explore on many levels.

An amazing array of likenesses, but the Missus and I agreed that these two Met portraits were the best of the lot.

From that quintessential French Impressionist figure, we moved on to a pair of quintessential New York figures.

First up: Helena Rubenstein: Beauty Is Power at the Jewish Museum.

This is the first exhibition to explore the ideas, innovations, and influence of the legendary cosmetics entrepreneur Helena Rubinstein (1872 – 1965). Madame (as she was universally known) helped break down the status quo of taste by blurring boundaries between commerce, art, fashion, beauty, and design. Through 200 objects Beauty Is Power reveals how Rubinstein’s unique style and pioneering approaches to business challenged conservative taste and heralded a modern notion of beauty, democratized and accessible to all.

Best story: Madame wanted a particular Manhattan apartment but was told Jewish tenants were not welcome. So she bought the building.

Beautiful. And very powerful.

A few blocks up Fifth, the Museum of the City of New York hosted Mac Conner: A New York Life.

The New York saga of one of the original “Mad Men.”

McCauley (“Mac”) Conner (born 1913) grew up admiring Norman Rockwell magazine covers in his father’s general store. He arrived in New York as a young man to work on wartime Navy publications and stayed on to make a career in the city’s vibrant publishing industry. The exhibition presents Conner’s hand-painted illustrations for advertising campaigns and women’s magazines like Redbook and McCall’s, made during the years after World War II when commercial artists helped to redefine American style and culture.

Here’s a great interview with the 100-year-old artist. (He lived to 106.) We should all do half as well.

As for our theater forays on that trip, we made the mistake of attending the 2014 revival of Edward Albee’s “A Delicate Balance,” as I noted at the time.

On the one hand, before I say anything about the current Broadway production of “A Delicate Balance,” I should mention that the Missus and I saw the vaunted 1996 production of the Edward Albee play described here by legendary New York Times theater critic Vincent Canby.

As staged by Gerald Gutierrez and acted by a splendid cast headed by Rosemary Harris, Elaine Stritch and George Grizzard, “A Delicate Balance” is now revealed to be almost as ferocious and funny as — and far more humane than — “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” It makes “Three Tall Women,” Mr. Albee’s 1994 Pulitzer winner, look as bland and unthreatening as a Saturday night dinner at your average upper-middle-class country club.

On the other hand, I should also mention that neither of us remembers all that much about the play itself, except that Rosemary Harris was a lot better than the current production’s Glenn Close (who flubbed about a dozen lines). Ditto George Grizzard vs. John Lithgow (who did a lot of scenery-chewing in the denouement). And Elaine Stritch – well, someone should have invoked the mercy rule for Lindsay Duncan’s performance.

Luckily, Rosemary Harris happened at the same time to be appearing Off-Broadway in Tom Stoppard’s Indian Ink, which was compelling from start to finish.

So that certainly cleansed the palate. And sent us home on a high note.

– to be continued –