By now those of you following our peripatetic adventures might think the Missus and I have traveled exclusively to foreign climes.

Not so!

Interspersed with our European jaunts, we’ve embarked upon periodic journeys all across this great land of ours. There was, for example, that sub-zero weekend in Chicago when the Hotel Knickerbocker was so desperate for business, it gave us not only a bargain-basement room rate, but also a free dinner in its tony restaurant (although we did have to pay for the two bottles of wine we drank). You bet we left a hefty tip that night.

Then there was the Louisiana plantation crawl that the Missus mapped out with military precision (we made one car ferry across the Mississippi River with just two minutes to spare), along with several trips to D.C. during which we visited, among other sites, the Freer Gallery of Art, home to James McNeill Whistler’s extravagant Peacock Room; the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, which features outdoor sculptures by Auguste Rodin, Alberto Giacometti, Henry Moore, Jeff Koons, and Yoko Ono; and The Phillips Collection, which houses more than 5000 works of modern and contemporary art.

Over the years we developed the Rule of Three: If there were three enticing cultural attractions – any combination of art exhibits, historic houses, theater productions – available in one place at one time, we’d consider going there.

And so we drove to Philadelphia in the summer of 1996 to take in 1) the legendary Barnes Foundation, 2) what would become a legendary Cézanne exhibit at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and 3) the Rodin Museum for a compare ‘n’ contrast with its Parisian counterpart, which we’d visited several years earlier.

Let’s start with the Barnes Foundation, which at that time still occupied its original location in the Philadelphia suburb of Merion. Here’s some background, via ArtDex.

Born to a working-class family, Albert C. Barnes was an American chemist and self-made millionaire. Barnes made his fortune as the co-developer of Argyrol in 1899, an antiseptic compound, consisting of silver and a protein, used to treat gonorrhea infections . . .

As Barnes’ company prospered and he benefited financially, Barnes was able to explore other interests, particularly in the arts and education. He started collecting pieces in the early 1900s, and in 1911, Barnes reconnected with his high school friend William Glackens, who would later become a realist painter and founder of the Ashcan School of American art. Glackens became one of Barnes’ early advisors in art collection and even sent him to Paris to purchase paintings for him.

By 1912, Barnes, who had just turned 40, was already considered a serious art collector as he’d acquired dozens of artwork that cost about $20,000 in total (worth over a half million today). On the heels of Glackens’ buying campaign, which included Van Gogh’s The Postman and Picasso’s Young Woman Holding a Cigarette, Barnes also traveled to Paris where he purchased his first two paintings by Henri Matisse from Gertrude Stein, a leading art collector of modernism and a host of Paris Salon.

Barnes went on to amass this staggering collection of artworks (via Wikipedia).

-

- 181 paintings by Pierre-Auguste Renoir

- 69 by Paul Cézanne

- 59 by Henri Matisse

- 46 by Pablo Picasso

- 21 by Chaïm Soutine

- 18 by Henri Rousseau

- 16 by Amedeo Modigliani

- 11 by Edgar Degas

- 11 by Giorgio de Chirico

- 7 by Vincent van Gogh

- 6 by Georges Seurat

Representative samples:

Getting into the Barnes Foundation was a bit of a production back then. You had to make reservations weeks in advance; the house was only open Fridays, Saturdays, and Sundays; and the number of visitors was restricted to 1200 per week (all of which was mandated by local officials).

But it was well worth it, as you can gather from this 2011 WHYY video tour of the Merion mansion.

Of course, there was nothing like seeing Albert Barnes’s magnificent collection in person. We felt extremely lucky to have done that before the art hit the fan at his foundation eight years later, about which more to come.

• • • • • • •

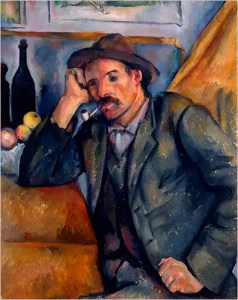

The other main attraction during that 1996 trip was Cézanne at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, billed as “[an] unprecedented gathering of some 100 oil paintings, 35 watercolors, and 35 drawings from public and private collections.” The exhibit arrived in Philly after stops at Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais in Paris and Tate Britain in London

Chicago Tribune critic Michael Killian submitted a smart, if slightly breathless, review at the time.

PHILADELPHIA — For art museum visitors, all roads this summer are leading to Philadelphia and its neo-classical landmark Museum of Art for what many consider the greatest Cezanne exhibition ever.

Some critics have disputed that assertion as a little hyperbolic, but by any measure this is an extremely significant and already hugely popular show. Organized by the Philadelphia museum, the Musee d’Orsay in Paris and London’s Tate Gallery, it’s the first major career retrospective showing of the artist’s work since the 1930s.

Paul Cezanne (1839-1906) is regarded as no less than the father of modern art, an opinion strongly held by Pablo Picasso, among other major figures of this century and the last.

Cezanne was no Michelangelo or Vermeer. As Washington Post art critic Paul Richard has observed, Cezanne had to work very hard to produce the kind of finished images a Degas could create with a few deft strokes.

Representative samples of that hard work . . .

As Kilian noted in the Tribune, “Cezanne’s genius, uncommon reputation and popular appeal have to do with his mind and eye, his color and line, the power of his brushstrokes. He could perceive and retrieve the very essence of an object or place–his legendary, deathly clock; his verdant French hillside landscapes. To other artists, his composition was akin to God’s.”

Overwrought? Perhaps. But not by much, as the Missus and I would come to see in a subsequent Cézanne exhibit at the Philly museum, which we will detail in due course.

• • • • • • •

During that ’96 trip to The City of Brotherly Love (excepting, of course, the town’s universally acknowledged worst sports fans ever), we also took in the requisite historic Philadelphia attractions, from the Liberty Bell and Independence Hall to the Betsy Ross House to the National Constitution Center.

Then we moseyed over to the Rodin Museum on Benjamin Franklin Parkway.

Philadelphia was the first city in the United States to exhibit works by Auguste Rodin. In 1876, the French artist sent eight sculptures to the Centennial Exposition held in Fairmount Park. His work was awarded no medals and the press made no mention of the young sculptor, leaving Rodin disappointed by his American debut. He had no idea the city would one day house one of the greatest single collections of his work outside of Paris.

The Rodin Museum and its vast collection are the legacy of one of the city’s great philanthropists, Jules E. Mastbaum (1872–1926) . . .

Although he had a long-standing interest in art, Mastbaum did not become a serious collector until the 1920s. In September 1924 he visited the fledgling Musée Rodin and left Paris after acquiring a small bronze bust by Rodin. By 1926 Mastbaum had amassed over two hundred sculptures by the artist, demonstrating Rodin as a sculptor of intimate works and great monuments.

Here’s a quick tour. Its Parisian counterpart at the time looked very similar.

Since then, the Paris Rodin Museum has undergone a major renovation, as Artnet’s Henri Neuendorf reported in 2015.

The Rodin Museum in Paris is set to reopen on November 12 following a three year, €16 million ($17.4 million) renovation. The reopening coincides with what would have been Auguste Rodin‘s 175th birthday.

The French artist created some of the best-known sculptures in art history, including The Thinker (1902), The Burghers of Calais (1884-1889) and The Kiss (1882-1889).

The 18th century Parisian mansion which Rodin used as his studio was already in a bad state of disrepair when the artist bequeathed the building—along with his entire estate—to the French state after his death in 1917.

The Missus and I toured the renovated museum in 2017 and it’s a knockout. But the Philly version is still well worth visiting.

• • • • • • •

In 2003 we returned to Philly on a trip about which I recall two things only: 1) our accommodations, and 2) the killer Degas exhibit at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

First, the hotel: As it happened, in the time between our reservation and our arrival, the property was sold to . . . no one seemed quite sure who, leaving the place largely devoid of both guests and staff.

But not us. While we were there, the hallways had this sort of eerie twilight quality, and the parking lot two blocks away was even more unsettling. Luckily, though, we escaped with our persons and property intact.

What made it all worthwhile in the end was tripping the light fantastic through the luminous Degas and the Dance exhibit.

Edgar Degas and the ballet are virtually synonymous. Dancers—shown in every phase of their complex and demanding art form—make up more than fifty percent of his abundant output.

A season ticket holder from his late teens, Degas haunted the corridors of the ballet school as well as the rehearsal halls and the stage itself. His insights into this closed, artificial, and finally enchanting world of female beauty and art reveals every aspect of the ballet, not just the accomplished public performance which, surprisingly, has a rather small role in his overall production . . ,

Through over 140 works in a variety of media the show explores Degas’s investigation over some forty years of the dance world that was central to the culture of Paris in his day.

It was a corker, and well worth the trip all by itself.

• • • • • • •

Six years after that we were back in the City of Batherly Love for Cézanne and Beyond at – you guessed it – the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Paul Cézanne’s posthumous retrospective at the Salon d’Automne in 1907 was a watershed event in the history of art. The immediate impact of this large presentation of his work on the young artists of Paris was profound. Its ramifications on successive generations down to the present are still in effect.

Artists take from other great artists when they need to become more themselves…

This exhibition features forty paintings and twenty watercolors and drawings by Cézanne, displayed alongside works by several artists for whom Cézanne has been a central inspiration and whose work reflects, both visually and poetically, Cézanne’s extraordinary legacy.

Here’s a smart tour of the exhibit. New York Times critic Karen Rosenberg dug even deeper in her review.

PHILADELPHIA — In the family of 20th-century art Cézanne’s patriarchal status is unquestioned. His “Bather” is, traditionally, one of the first paintings you see in the Museum of Modern Art’s permanent-collection galleries. The statement “Cézanne is the father of us all” has been attributed to Picasso and to Matisse.

“Cézanne and Beyond,” at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, refines that lineage for the 21st century. It builds on the museum’s 1996 Cézanne blockbuster, interspersing the works of 18 modern and contemporary artists among some 40 paintings and 20 drawings and watercolors by the prolific master of Aix-en-Provence.

Many of these artists knew Cézanne (1839-1906) primarily through his paintings and writings (and sometimes, as was the case with the Italian still-life master Giorgio Morandi, through printed reproductions). But they shared an almost monotheistic faith in his art. As Matisse said, “If Cézanne is right, then I am right.”

Sounds about right.

Picasso and Matisse weren’t Cézanne’s only fanboys: “The exhibition takes a nonlinear form,” Rosenberg wrote, “with several smaller galleries branching out from a showstopping central room of Cézanne, Picasso and Matisse. Some artists (Fernand Léger, Liubov Popova) make brief appearances; others (Marsden Hartley, Jasper Johns, Ellsworth Kelly) are recurring characters.”

For example, Marsden Hartley’s New Mexico Landscape . . .

. . . or Ellsworth Kelly’s Apples.

As Rosenberg concluded, some of the works inspired by Cézanne “come to seem almost slavish. The Cézannes, meanwhile, remain inscrutable.”

As Matisse said of the “Three Bathers”: “In the 37 years I have owned this canvas, I have come to know it quite well, though not entirely, I hope.” Or [Brice] Marden, on another version of the “Bathers”: “It is one of the most complex, weird paintings I have ever seen, and I can never deconstruct it: I get it and I still just don’t get it.”

The Missus and I just felt grateful we got to see it at all.

We also revisited the Barnes Foundation, which would soon exit its original home in Merion (more on that dreary, dragged-out domestic dustup below). We found the old Barnes [checks notes] exactly the same, which was just as it should have been.

Last and – no offense – least was the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, which made virtually no impression on me beyond an introduction to the paintings of Thomas Eakins, such as this portrait of Walt Whitman.

And then there was Eakins’s Portrait of Dr. Samuel D. Gross (The Gross Clinic), which Aline Cohen wrote in Artsy “may be the most important American painting.”

Most important? Or maybe just the most surgical. Then again, what do I know.

• • • • • • •

Now to the finale of the protracted tong war over relocating the Barnes Foundation (see here and here for all the gory details). Nutshell version: In 2012 the collection went kicking and screaming from its Renaissance-style home in Merion . . .

. . . to this blocky behemoth on Benjamin Franklin Parkway.

The reviews were decidedly mixed. The Barnes, for its part, touted Paul Goldberger’s Vanity Fair piece, which sported the headline “The New Barnes Foundation Building: Soulful, Self-Assured, and Soaked with Light.”

Drive the Merionites nuts graf:

This building won’t please the absolutists, the people we should probably call Barnes fundamentalists, because nothing would please them short of a return to the way things were. But it really ought to please everybody else, because—to cut to the chase—the new Barnes is absolutely wonderful. The court order allowing the foundation to relocate the collection to Philadelphia specified that the pictures were to be hung exactly as they had been in suburban Merion, in galleries that had to duplicate the configuration and the proportions of Paul Cret’s. It was a requirement that could have been stifling, a prescription for trite replication, as if the court, seeking to mollify the people who were arguing against any changes to the Barnes, had ordered up a Barnes theme park.

But that is not what Philadelphia has gotten.

New York Times art critic Roberta Smith also lauded the Barnes-burning in her review headlined, “A Museum, Reborn, Remains True to Its Old Self, Only Better.”

Drive the Merionites even nutser graf:

Against all odds, the museum that opens to the public on Saturday is still very much the old Barnes, only better.

It is easier to get to, more comfortable and user-friendly, and, above all, blessed with state-of-the-art lighting that makes the collection much, much easier to see. And Barnes’s exuberant vision of art as a relatively egalitarian aggregate of the fine, the decorative and the functional comes across more clearly, justifying its perpetuation with a new force.

To recap: The new digs are purportedly a) not a Six Flags Over Barnes theme park, and b) so much easier on the eyes!

Other art critics, however, were having none of it. Start with Christopher Knight’s Los Angeles Times jihad.

PHILADELPHIA — Saturday the Barnes Foundation opens its new museum here on the busy Benjamin Franklin Parkway. With hundreds of Renoirs, Cézannes, Matisses and Picassos, it’s just up the street from the Philadelphia Museum of Art, whose officials were instrumental in pulling strings to make it happen.

Anticipation has been running high. Eight years ago a local judge granted permission for the incomparable art installation to relocate from its unique home out on the Main Line, available to anyone who wished to visit. And 17 years after the idea of moving was hatched, the deed is done.

Deed is perhaps too mild a word. (The New Yorker magazine called the plan “an aesthetic crime.”) A deeply personal, eccentric installation of often jaw-dropping art in a specially designed building within a 12-acre garden, the ensemble was a total artwork. Once the nation’s greatest cultural achievement pre-World War II, it has now become America’s weirdest art museum.

The New Republic’s art critic Jed Perl went even further, calling it “a disastrous new home” for the Barnes Foundation.

THE BARNES FOUNDATION, that grand old curmudgeonly lion of a museum, has been turned into what may be the world’s most elegant petting zoo. I am not surprised that the members of the press, after touring the Foundation’s new home on Benjamin Franklin Parkway in Philadelphia, have by and large been pleased. We live in a period when everything is supposed to be easy, whether preparing dinner, accessing the news, or looking at art. And the old Barnes, for three quarters of a century a splendidly ornery landmark in Merion, a suburb of Philadelphia, was not easy. It was a bit hard even to get there. And once you arrived you were confronted with a fearsome onslaught of masterworks and, at least in recent years, pretty much left on your own.

The sensory overload at the Barnes could be daunting, with seminal paintings by Cézanne, Renoir, Seurat, Matisse, and Picasso competing for a visitor’s attention with a great many other extraordinary things . . .

The new Barnes tiptoes around the unruly power of the old Barnes, approaching the wild beast with an excess of solicitude. By the time museumgoers actually arrive in the galleries, they feel so coddled and cared for that the vehement visions of Cézanne, Seurat, Renoir, Matisse, Picasso, and a host of others are most likely not going to register, at least not in the way that Barnes hoped they would. The sink-or-swim intensity is gone. The new Barnes is nice to museumgoers. “Nice” was not a word that came to mind after a visit to Merion.

One last whack from Lee Rosenbaum in The Huffington Post.

The bizarre project (memorialized in a 2004 court decision) to replicate in Philadelphia the galleries of the original 1925 facility in Merion, Pa., flagrantly disregards a primary mission of art institutions to defend the glory of the original against the taint of the spurious. The Barnes once upheld that principle to the point of fanaticism, not even allowing copies of its artworks to be made. Now the institution itself is counterfeit.

As night follows day, once the Movers had picked the lock of the Merion mansion, it was Albert, bar the door, as Rosenbaum subsequently noted in her CultureGrrl blog.

I guess it was just a matter of time before the Barnes Foundation, once an intimate, inviting setting for enjoying art and nature in bucolic surroundings, took the (once unthinkable) step of making temporary art loans to other institutions—a deviation from the late Albert Barnes’ trust indenture, which set forth specific strictures governing the operation of his eclectic, eccentric treasure trove in the purpose-built, Paul Cret-designed mansion where he had explicitly stipulated that everything should always remain exactly as he left it.

Regardless, here’s the Barnes Foundation’s virtual tour of its new digs.

About five years after the museum’s relocation, the Missus and I were back in Philly for a wedding and we visited the relocated Barnes, about whose new home I gingerly weighed in afterward.

Now, I am nowhere near as smart as the aforementioned art critics, but it seems to me that if the Barnes Foundation had to be moved (the question at the very heart of that whole rumpus), what now sits on Benjamin Franklin Parkway (cost: north of $150 million) is about the best we could have expected.

There. That should tick off both sides.

And then, we were all done with the Barnes-razzing.