-

Epilogue: Some Final Snapshots From Our Many Excellent Adventures

In the process of chronicling our four-plus decades of carefree rambles, the Missus and I have inevitably let some journeys slip through the cracks. So we’ll gather up a few of the leftovers before we say goodbye.

White Knuckles at the Grand Canyon

The Missus, in her entrepreneurial heyday, travelled all across this great land of ours for her many clients in the footwear and fashion industries, forecasting trends and previewing product lines.

From time to time I would join her in my capacity as Chairman of the Board (with, as you might recall, the major responsibility of schlepping luggage through airports both domestic and international).

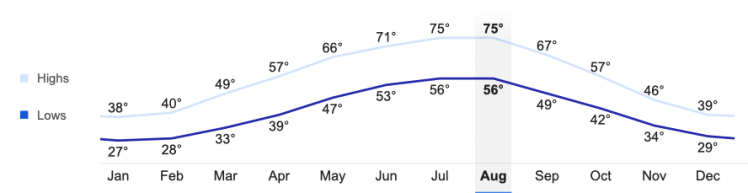

One such occasion found us in Phoenix, Arizona in August, where the mercury soared to 104° – at night. Upon her successful completion of some sales meeting or other, the Missus and I set off to explore the many natural wonders of the Grand Canyon State.

Our first stop was scheduled to be Sedona, but an hour and a half into the drive we veered off at Montezuma Castle National Monument, home of “the well-preserved living spaces of the Sinagua Indians.”

Like an ancient five-story apartment building, Montezuma Castle towers above the desert below, a stone-and-mortar marvel of early architectural engineering. Experts have determined that the Castle was built over three centuries and provided shelter for the Sinagua Indians during flood seasons. However, contrary to the belief of the European-Americans who discovered the structure, there’s no historical connection to the Aztec emperor for whom it’s named—the structure was abandoned more than 40 years prior to his birth.

Right. So to recap: Not a castle, not Montezuma’s, and you couldn’t go inside. Other than that, it was swell . . . for about ten minutes. Unfortunately for the bus-tour folks standing alongside us (part of the “approximately 350,000 people per year [who] visit the Castle”), they were there for an hour. We, on the other hand, were on our merry way to Red Rock Country.

Upon arriving in Sedona (“Plan to stay more than a day”), we checked into the Matterhorn Motor Lodge (as it was called at the time) for one night. According to its website, “The Matterhorn Inn in Sedona, Arizona offers elegant accommodations with unparalleled views of the red rock mountains, all at budget-friendly rates.”

Half of that was true when we stayed there 30 years ago. On the one hand, elegant the Matterhorn Motor Lodge was not. Case in point: Despite the extreme heat, the pool area was entirely deserted, most likely because the pool itself was half filled with brownish, brackish water. I don’t even want to talk about the hot tub.

On the other hand, the place was budget-friendly. The Missus assured me we were paying far less than 50,000 kronkites for our room. After all, it wasn’t exactly the Schmatterhorn.

As for Sedona, it has a reputation as as a town suffused with a New Agey “vortex vibe,” as Dwight Garner noted in the New York Times some years ago.

There’s a vibe in the air, something not quite audible, a kind of metaphysical dog whistle that calls people out to have a look around and to try to feel something that, if you’re not a committed New-Age pilgrim, is hard to put into words . . .

Sedona is famous for its so-called vortex sites, spots where the earth’s energy is supposedly increased, leading to self-awareness and various kinds of healing. (Think of them as spiritual hot tubs without the water.)

In keeping with the whole vortex thing, we decided to take a Jeep tour of the fabled “red sandstone cliffs and giant red sandstone spires.” And lucky us: Our driver was not only straight out of central casting (Throwback Hippie, circa 1969), he was also – he announced as we set out – psychic and clairaudient (“the supposed faculty of perceiving, as if by hearing, what is inaudible”).

Oddly enough, though, he seemed entirely incapable of hearing the moans and groans of his passengers as the Jeep careened at teeth-rattling speeds across the rugged terrain.

Regardless, the landscape was indeed spectacular. As Dwight Garner wrote, “Nowhere else in this country does a natural setting feel so much like the inside of a soaring pantheistic cathedral.”

• • • • • • •

About hallway between Sedona and Grand Canyon National Park, the Missus and I rumbled into Bedrock City, the purported home of The Flintstones and the longtime home of Raptor Ranch, a tourist trap that can’t even spell its own catchphrase correctly. The current headline on Raptor Ranch’s website is “Yabadabaoo [sic]! Come and Celebrate 50 Years of Iconic Bedrock City,” although they did get the Yabbas right on their sign along the highway.

Unsurprisingly, we gave Bedrock the swift, cruising half an hour later into the National Park Service’s Kachina Lodge, which featured all the charm and ambiance of a 1960s cinder-block college dorm.

But, man, location location location.

Sitting directly on the rim of Grand Canyon in the center of the historic Village, this lodge is within close walking distance to restaurants, gifts shops, Kolb Studio, Verkamp’s Visitor Center, and Bright Angel Trailhead.

Kachina Lodge was built in 1968 as part of a plan by the National Park Service to expand services at parks across the country. The tiered design of Kachina Lodge mimics the uppermost layers of rock in Grand Canyon.

Next thing we knew, we ourselves were directly on the rim of the Grand Canyon, and – as I’m sure millions of gawkers have said before – grand doesn’t even come close to describing it.

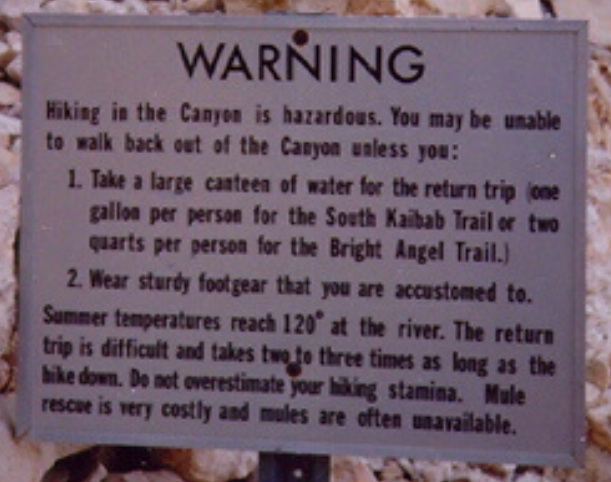

Also like legions of others before us, we wanted to see the canyon up close. So bright and early the next morning, we headed down the nearest hiking trail. We’d gone maybe a third of a mile when we encountered a sign similar to this one.

We didn’t have to be told twice. As the Missus and I trudged back up the trail, we encountered several tourists striding briskly toward us.

“Hey, did you go all the way to the bottom?” one asked brightly.

“Oh yeah,” the Missus replied. “Don’t let the sign down there bother you.”

Mind you, the Missus was dressed entirely in white – someone alert Ripley’s, right? – without a speck of trail dirt on her. No sweat stains, either. Regardless, the group continued down as we proceeded up.

(Spoiler alert: They were back at the rim shortly after we were.)

Meanwhile, the Missus and I shifted to Plan B: An airplane tour of the Big Hole. Here’s a short promotional video for one of the canyon tours.

Full disclosure: The couple in the video is way calmer than the Missus and I were during our ride. I truly believe that somewhere in the skies above Arizona, there are two airplane seatbacks that still bear the impressions of our fingers tightly clutching them throughout the flight.

Laugh, clown, laugh. But not long after our Tour of Terror, there was this story in the Tampa Bay Times.

A tour plane carrying passengers over the Grand Canyon apparently lost an engine Monday and crashed while trying to return to the airport.

Eight of the 10 people on board were killed.

The PA-31 Navajo aircraft developed engine trouble shortly after liftoff Monday from Grand Canyon Airport and went down in a ravine as it returned for an emergency landing, said FAA spokesman Fred O’Donnell.

Over all, we were more than happy to drive back to Phoenix.

In yet another personal and professional triumph, the Hotel Booking Goddess had snagged a room at the legendary Frank Lloyd Wright-designed Arizona Biltmore – for $85 per night, a steal even back then.

On February 23, 1929 the Arizona Biltmore opened in grand fashion. Over 600 invitations were sent out, with the thought of only a few hundred attending, but it seemed no one wanted to be left out and the resort had to re-create the opening gala three days in a row to accommodate all 600 people. From that day forward, the Arizona Biltmore has been a private retreat for some of the most influential powerhouses of the time.

“Influential powerhouses” decidedly did not describe the two of us at the time, but we strolled around the place like we owned it nonetheless.

One example of our devil-may-care attitude: Despite the strict prohibition against cutoff jeans in the pool area, I wore mine anyway. For one thing, I didn’t have any other shorts with me; for another, lots of people poolside wore next to nothing, so my transgression went largely unnoticed.

Phoenix wasn’t much of a museum town back then, but we did trundle over to the Heard Museum, “recognized internationally for the quality of its collections [of American Indian art], world class exhibitions, educational programming and unmatched festivals.”

Such as the Hopi Indian Festival, which we found to be aptly named, since it featured exactly one Hopi Indian.

“It’s a corker!” the pleasant white-haired gal at the ticket counter told us, by which of course she meant he’s a corker.

And he sort of was. But no matter – all in all, our Arizona trip was a total hoot.

Postscript: As we traversed the great state of Arizona, we also encountered two of its three major sinkholes back then. These days, apparently, there are a lot more.

Hip Hip . . . Replacement!

The first time the Missus went to England to check out the European fabric shows and divine coming color trends for her footwear clients, I wound up – in a one-time only event – doing a bit of business there myself.

I was preparing to assume my assigned role of corporate arm candy/airport skycap on the trip, when my penny-pinching boss at the ad agency I worked for said, “Say, since you’re going to be in London anyway, you should pop by our client’s headquarters there to generate some good will and collect a few invoice payments.”

I quickly pointed out that our improbable international client – Charnley Limited, founded by John Charnley, the inventor of the modern hip replacement – was headquartered in the city of Leeds, a good four-hour drive from London.

“Excellent,” he replied briskly. “You can take in the countryside along the way.”

So it was that early one morning the Missus and I piled into a rental car and headed toward Leeds. We exited London via the Uxbridge Road, about which I remember two things: 1) The road’s name changed every few miles, making us think we were lost for the first 45 minutes of the trip; and 2) The road took us through the heart of Brixton, which was experiencing one of its periodic race riots protesting police brutality

Other than that, a smooth ride with some lovely countryside along the way.

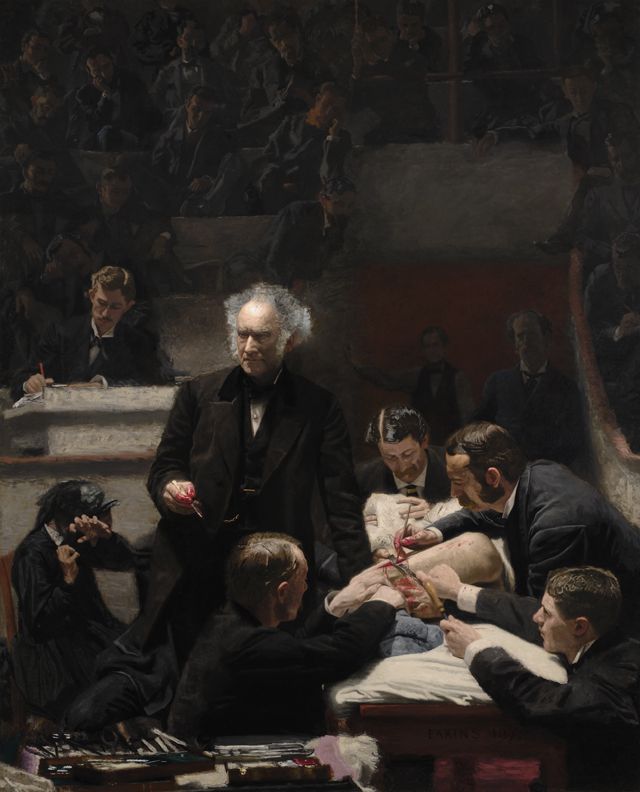

Here’s the backstory on John Charnley, the company’s namesake, compliments of Yale University Library.

Surgeons’ efforts before the 1960s laid the groundwork for Sir John Charnley to develop his

revolutionary low-friction arthroplasty of the hip. His procedure was the first to consistently achieve predictable and positive outcomes due to the incorporation of a reliable socket replacement. Dr. Charnley’s novel total hip replacement combined a small femoral head in a molded plastic socket with both of these prosthetic components secured in position by fast-setting bone cement. The immediate clinical success of his arthroplasty rapidly became the new gold standard for hip replacement surgery.

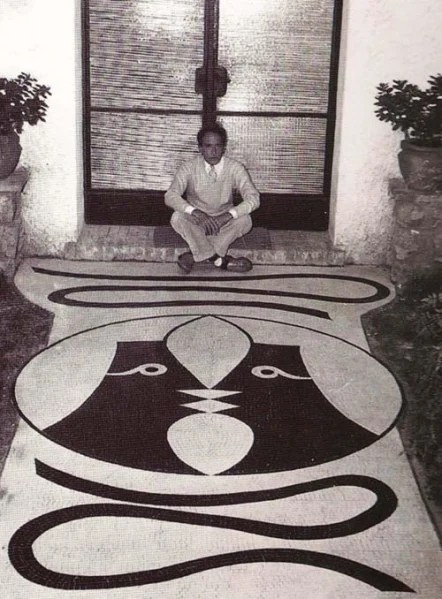

revolutionary low-friction arthroplasty of the hip. His procedure was the first to consistently achieve predictable and positive outcomes due to the incorporation of a reliable socket replacement. Dr. Charnley’s novel total hip replacement combined a small femoral head in a molded plastic socket with both of these prosthetic components secured in position by fast-setting bone cement. The immediate clinical success of his arthroplasty rapidly became the new gold standard for hip replacement surgery. Coincidentally, the year before our trip to Leeds, Sammy Davis Jr. had undergone a hip

replacement – a Charnley hip, as it happened. So I decided, in all my marketing wisdom, to make an impromptu pitch to the company’s executives in our meeting.

replacement – a Charnley hip, as it happened. So I decided, in all my marketing wisdom, to make an impromptu pitch to the company’s executives in our meeting.“How about,” I said brightly, “if we get Sammy Davis Jr. to endorse the Charnley replacement, given that he’s got one. We could feature him in an ad with the tagline “The Hip Hip.”

When that failed to get any “hoorays” from the stone-faced execs, I said, “Do you know who Sammy Davis Jr. is?”

One of the underlings hovering in the background quickly handed me a couple of checks and showed me the door. And that was the end of the Great Lost Hip Hip advertising campaign. Also the end of that client for my two-pence ad agency.

The end of Charnley Limited, on the other hand, came 30 years later, when the company was declared insolvent. I’m not saying Sammy Davis Jr. could have forestalled that fate, but you never know, right?

• • • • • • •

On our way back to London, the Missus and I decided to stop off at Warwick Castle, “the finest medieval castle in England” according to this UK advert that was on TV at the time.

Narrator: “If you’ve never seen the Great Wall of China, or journeyed up the Amazon, that’s understandable. But if you live in the heart of England and haven’t seen the splendors of Warwick Castle, well . . . Towering ramparts, breathtaking views, priceless historical treasures, and the unique weekend royal party by Madame Tussaud’s. This is what visitors come thousands of miles to see.”

That was me and the Missus! When we arrived at Warwick Castle, we were the only ones there, except for (wait – what?) the Bishop of Warwick. His name was Keith Arnold, “an English Anglican clergyman who served as the inaugural Bishop of Warwick from 1980 to 1990.”

Why he was roaming around an empty castle on a weekday afternoon is anyone’s guess. But he was extremely cordial to us, so that was lovely.

(Travel Advisory: In the intervening 40 years, Warwick Castle has apparently been turned into a tourist trap that doesn’t quite rival Bedrock’s Raptor Ranch, but seems to be trending in that direction.)

After bidding the bishop goodbye, the Missus and I drove back to London. And then we flew back home.

And We’ll Be in Scotland Afore Ye (Know It)

During one of our myriad sallies to London for the Missus to ferret out future American fashion trends, we nipped up to Scotland for a few carefree days in the great city of Edinburgh.

Once again the Hotel Booking Goddess outdid herself, putting us up at the Dalhousie Castle Hotel, “where history meets modern luxury.”

For over 800 years, Dalhousie Castle has witnessed triumphs and tragedies, battles and dungeons, and the enduring legacies of kings and queens . . .

Originally, guests would cross a drawbridge over a dry moat to enter. The moat remains today, and you can still see the holes from the drawbridge mechanisms and the machicolations castle guards would use to drop nasty surprises on invaders below. It’s safe to say, today’s visitors are greeted with a much warmer welcome.

Indeed it was. We were assigned the turreted Room 4, which required ascending multiple staircases. Unfortunately, on a trip to the London suburbs several days earlier, the Missus had suffered a severe ankle sprain while sprinting for a train. Regardless, she gamely – gam-ly? – soldiered up to the spectacular room.

The rest of the hotel was equally dazzling. We sat in the (really) Great Room on a leather-bound sofa large enough that the Missus could stretch out from one end and I could stretch out from the other, and our feet didn’t touch.

The single malt Scotch I sipped on that sofa was equally memorable. As was the lavish dinner the Missus and I savored in the Dalhousie’s dungeon restaurant.

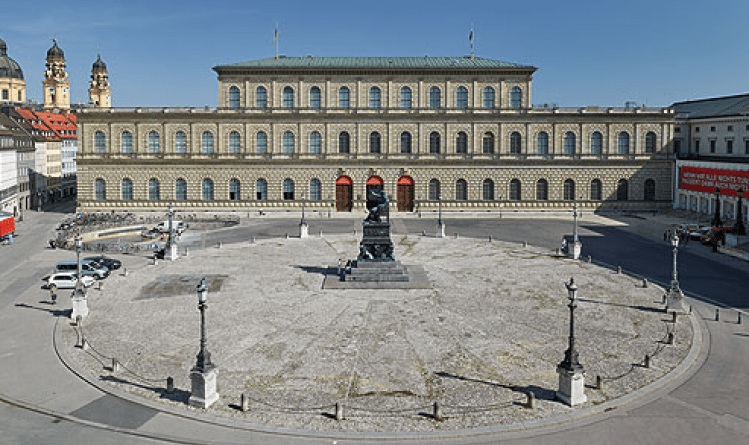

Other than that, our time in Scotland remains a bit hazy after all these years. But I do know we visited Edinburgh Castle, “the most besieged castle in Britain . . . attacked 23 times throughout history.”

The fortification resides high atop Castle Rock, an extinct volcanic outcrop in the center of Edinburgh. Although the human occupation of Castle Rock dates back to the 2nd century, the oldest portion of the current structure exists from the 12th century during the reign of King David I. In 1093, his mother, Queen Margaret, died at the castle upon hearing her husband, King Malcolm III, was killed in battle. Thereafter, David built St. Margaret’s Chapel to honor his recently deceased mother.

Centuries of murder and mayhem ensued, much of which is detailed here, for those of you keeping score at home.

We also visited the Palace of Holyroodhouse, “the official residence of King Charles the 3rd when he is in Scotland,” although Chuckles was a mere monarch wannabe when we were there in the early ‘90s.

(QE II preferred Balmoral Castle for her Scottish stays, but then she always was more rugged than Sonny Boy.)

Lucky for Chucky, Holyrood has a far less bloody history than Edinburgh Castle.

The ruins still visible on the grounds were once an Augustinian Abbey ordered by King David I of Scotland. The name Holyrood comes from either the legendary vision of the cross witnessed by the King or from a relic of the True Cross, known as the Holy Rood.

After the Union of Scotland and England in 1707, the palace began to fall into disrepair. When Bonnie Prince Charlie moved into the palace, he chose the Duke’s apartments over the unkempt King’s. Neglect continued as the abbey church roof collapsed, leaving it as it currently stands.

George V transformed Holyroodhouse into a 20th-century palace with the installation of central heating and electric lighting, modernising the kitchens and fitting a lift. The palace was selected as the site of the Scottish National Memorial to Edward VII and formally designated as the monarch’s official residence in Scotland.

The Missus and I were especially taken by the Great Gallery, a grand room filled with 110 portraits of Scottish monarchs real and legendary, all created by Dutch artist Jacob de Wet.

(Here’s a quick walkthrough if you’re so inclined.)

We ventured outside of Edinburgh as well, first to the Firth of Forth – partly because it sounded cool, partly because it is cool (actually, frigid that day).

The UK site Cottages and Castles describes it this way.

The Firth of Forth is the estuary, or firth, of the River Forth and opens at the easternmost tip of Stirling, stretching out past Edinburgh and the Kingdom of Fife before connecting up with the North Sea.

It really is the gateway to the rest of Scotland, with its three iconic bridges that allow for easy transport links, and is a worthwhile destination in itself due to the rich history of its islands and the stunning vistas that the three bridges offer.

Those bridges include The Queensferry Crossing . . .

The Forth Road Bridge . . .

and The Forth Bridge.

Each an excellent bridge in its own right.

From the FofF we drove to Stirling Castle, which sits atop a volcanic crag, provides spectacular views of the surrounding countryside, and that day featured weather straight outta King Lear (Blow, winds, and crack your cheeks!).

Stirling Castle, historically and architecturally significant castle, mostly dating from 15th and 16th centuries, in Stirling, Scotland. Dominating major east–west and north–south routes, the fortress’s strategic importance gave it a key role in Scottish history. Standing 250 feet (75 m) higher than the surrounding terrain on the flat top of an ancient extinct volcano above the River Forth and commanding excellent views in every direction, it was the principal royal stronghold of the Stuart kings from the time of Robert II until the union of Scotland and England in 1707. Whoever held Stirling, it was said, had the key to Scotland.

Who had the key to Stirling Castle? Steward Brian Gibson, who worked at the historic site for 22 years, starting shortly after the Missus and I were there.

Here’s his guided tour of the castle, well worth four minutes out of your day.

Of course, we couldn’t depart Scotland without a nod to Greyfriars Bobby, the official Who’s a Good Boy of Edinburgh.

In 1850 a gardener called John Gray, together with his wife Jess and son John, arrived in Edinburgh. Unable to find work as a gardener he avoided the workhouse by joining the Edinburgh Police Force as a night watchman.

To keep him company through the long winter nights John took on a partner, a diminutive Skye Terrier, his ‘watchdog’ called Bobby. Together John and Bobby became a familiar sight trudging through the old cobbled streets of Edinburgh. Through thick and thin, winter and summer, they were faithful friends.

The years on the streets appear to have taken their toll on John, as he was treated by the Police Surgeon for tuberculosis.

John eventually died of the disease on the 15th February 1858 and was buried in Greyfriars Kirkyard. Bobby soon touched the hearts of the local residents when he refused to leave his master’s grave, even in the worst weather conditions.

According to legend, Bobby stood guard over his late master’s grave for 14 years. The headstone on the fountain erected in his memory reads “Greyfriars Bobby – died 14th January 1872 – aged 16 years – Let his loyalty and devotion be a lesson to us all.”

(Then again, not everyone is on board the Bobby Train. Killjoys can read all about Debunking the Myth of Greyfriars Bobby, if you like that sort of thing.)

After that, we took the high rode (a.k.a. British Air) back to Boston.

Postscript: While we were assembling this epilogue, the Missus and I learned of the death of the great travel guru, Arthur Frommer.

Paul Vitello’s New York Times obituary nicely captured Frommer’s underlying approach to visiting Europe when he published his first guidebook in 1957.

To Mr. Frommer, travel wasn’t just about sightseeing in foreign places; it was about seeing those places on their own terms, removing the membrane that separated them from us. In short, it was about enlightenment. And with the affordability that he could guarantee, it was practically middle-class Americans’ democratic duty, to hear him tell it, to exercise their inalienable right to see London, Paris and Rome.

To Mr. Frommer, travel wasn’t just about sightseeing in foreign places; it was about seeing those places on their own terms, removing the membrane that separated them from us. In short, it was about enlightenment. And with the affordability that he could guarantee, it was practically middle-class Americans’ democratic duty, to hear him tell it, to exercise their inalienable right to see London, Paris and Rome.“This is a book,” he wrote, “for American tourists who a) own no oil wells in Texas, b) are unrelated to the Aga Khan, c) have never struck it rich in Las Vegas and who still want to enjoy a wonderful European vacation.”

The Hotel Booking Goddess found the Frommer’s guides to be an invaluable resource – but just

one of many. She grew up in New York, so “Trust but Verify” was a lifelong motto.

one of many. She grew up in New York, so “Trust but Verify” was a lifelong motto.The Missus would prowl local bookstores for travel guides and take notes to compare ‘n’ contrast recommendations. She was, in short, the Human Search Engine That Could. (And did, as the previous posts so amply attest.)

Of all the sources the Missus consulted over the years, Frommer’s Travel Guides proved to be the most often verified and most often trustworthy.

Now the author of those guide books has traveled to his final destination. Rest in peace, Arthur Bernard Frommer. Here’s guessing you wound up in a very nice place.

-

The Arts Seen in New York City (Act Three)

(Previously on Travels With The Missus: As noted earlier, the visits the Missus and I made to the Big Town were largely sporadic for most of the 2010s. They picked up considerably, though, during 2018 and 2019. A good thing too, given what awaited us at the turn of the decade.)

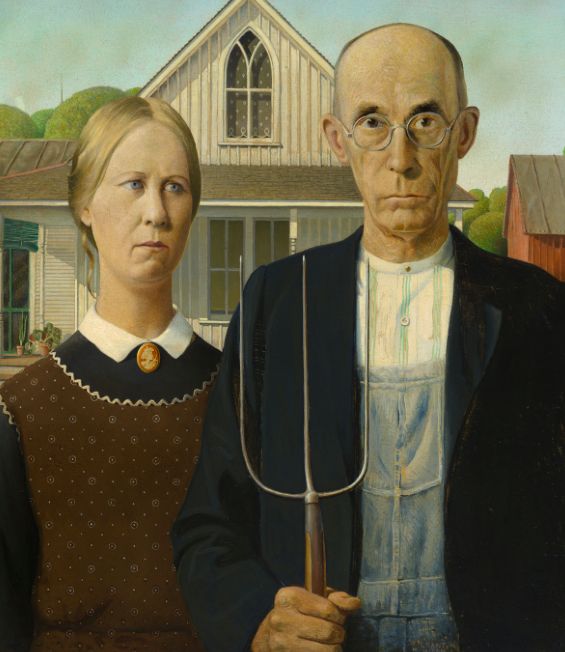

When the Missus and I finally got back to the city in March of 2018, our first stop was the Whitney Museum to catch Grant Wood: American Gothic and Other Fables. As I noted back then, here’s what 99% of the world that knows about Grant Wood knows about Grant Wood.

But there’s more to the artist than one painting of what’s routinely referred to as a Midwestern couple but which was really meant to depict a father and daughter (in real life it was Wood’s sister and his dentist), as the Whitney exhibit explains.

Grant Wood’s American Gothic—the double portrait of a pitchfork-wielding farmer and a woman commonly presumed to be his wife—is perhaps the most recognizable painting in 20th century American art, an indelible icon of Americana, and certainly Wood’s most famous

artwork. But Wood’s career consists of far more than one single painting. Grant Wood: American Gothic and Other Fables brings together the full range of his art, from his early Arts and Crafts decorative objects and Impressionist oils through his mature paintings, murals, and book illustrations. The exhibition reveals a complex, sophisticated artist whose image as a farmer-painter was as mythical as the fables he depicted in his art. Wood sought pictorially to fashion a world of harmony and prosperity that would answer America’s need for reassurance at a time of economic and social upheaval occasioned by the Depression. Yet underneath its bucolic exterior, his art reflects the anxiety of being an artist and a deeply repressed homosexual in the Midwest in the 1930s. By depicting his subconscious anxieties through populist images of rural America, Wood crafted images that speak both to American identity and to the estrangement and isolation of modern life.

artwork. But Wood’s career consists of far more than one single painting. Grant Wood: American Gothic and Other Fables brings together the full range of his art, from his early Arts and Crafts decorative objects and Impressionist oils through his mature paintings, murals, and book illustrations. The exhibition reveals a complex, sophisticated artist whose image as a farmer-painter was as mythical as the fables he depicted in his art. Wood sought pictorially to fashion a world of harmony and prosperity that would answer America’s need for reassurance at a time of economic and social upheaval occasioned by the Depression. Yet underneath its bucolic exterior, his art reflects the anxiety of being an artist and a deeply repressed homosexual in the Midwest in the 1930s. By depicting his subconscious anxieties through populist images of rural America, Wood crafted images that speak both to American identity and to the estrangement and isolation of modern life.You’ll find lots more of Wood’s work – from decorative arts to drawing to murals and more – here. The Missus and I kind of liked this corncob chandelier he designed for a number of hotels . . .

. . . and got a kick out of his Lilies of the Alley series.

The New Yorker’s Peter Schjeldahl, however, was far less kind.

[Wood] was a strange man who made occasionally impressive, predominantly weird, sometimes god-awful art in thrall to a programmatic sense of mission: to exalt rural America in a manner adapted from Flemish Old Masters. “American Gothic”. . . made Wood, at the onset of his maturity as an artist, a national celebrity, and the attendant pressures pretty well wrecked him. I came away from the show with a sense of waste and sadness.

We, on the other hand, came away from the show with a sense of wanting to visit The Museum at FIT, which featured Norell: Dean of American Fashion, a smart retrospective tracing the career of Norman Norell, “one of the greatest fashion designers of the mid-twentieth century . . . best remembered for redefining sleek, sophisticated, American glamour.”

Very glamourous, indeed.

Far more fun, though, was Pockets to Purses: Fashion + Function. Our favorite was this Rod Keenan chapeau from 2006.

A whole new way to keep something under your hat, yes?

The next morning we embarked on a Backward Museum Mile, starting at the Museum of the City of New York and working our way south. We took the bus up Madison to 103rd Street, which was a first for me: Growing up at 89th & Third during the ’50s and ’60s, I’d been repeatedly warned never to set foot north of 96th Street. Times do change, don’t they.

Coincidentally, the main exhibit at MCNY was Mod New York: Fashion Takes a Trip.

The world of fashion was turned on its head in the 1960s, as its traditions were challenged, rejected, and reimagined for the restless next generation. Beginning with the introduction of First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy as a new American style icon and evolving over the course of the decade, fashions of the 1960s were legendary for their energy, their ingenuity, and their enduring appeal. Their influence was far-reaching—many of the era’s defining styles have been invoked by new generations of designers. Yet the scope of the decade’s trends far exceeds its iconic miniskirt, color-block dress, or bohemian spirit. Mod New York: Fashion Takes a Trip explores the full arc of 1960s fashion, shedding new light on a period marked by tremendous and daring stylistic diversity.

Talk about your Wayback Machine.

New York on Ice: Skating in the City was also a delightful trip down Memory Lane, while New York Silver, Then and Now was, well, sterling.

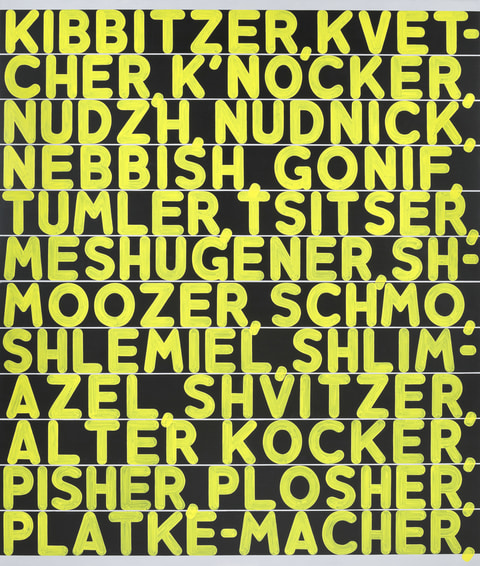

From MCNY we dropped down to the Jewish Museum for Veiled Meanings: Fashioning Jewish Dress, from the Collection of The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, which frankly I didn’t get because I have a goyishe kop. But I totally got Scenes from the Collection, “a new, major exhibition of the Jewish Museum’s unparalleled collection featuring nearly 600 works from antiquities to contemporary art — many of which will be on view for the first time.”

Among those works were Mel Bochner’s The Joys of Yiddish . . .

. . . and Louise Nevelson’s Self-Portrait.

L’Chaim!

From there it was on to the Neue Galerie for Before the Fall: German and Austrian Art of the 1930s.

This exhibition, comprised of nearly 150 paintings and works on paper, will trace the many routes traveled by German and Austrian artists and will demonstrate the artistic developments that foreshadowed, reflected, and accompanied the beginning of World War II. Central topics of the exhibition will be the reaction of the artists towards their historical circumstances, the development of style with regard to the appropriation of various artistic idioms, the personal fate of artists, and major political events that shaped the era.

Such as Mother and Eva by Otto Dix . . .

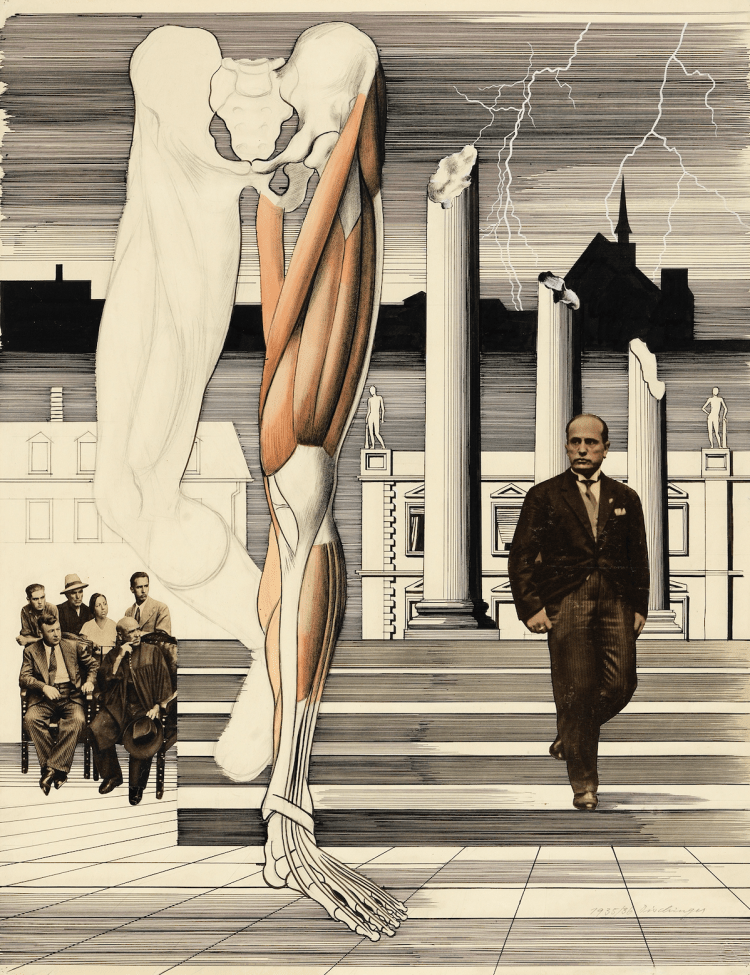

. . . and Striding by Rudolf Dischinger.

The Missus: “As someone who loves German Expressionism, I think this exhibit is creepy and not very good.”

Ditto.

So we moved on to The Met, where we made a beeline for Birds of a Feather: Joseph Cornell’s Homage to Juan Gris – “18 boxes, two collages, and one sand tray created in homage to Juan Gris, whom [Cornell] called a ‘warm fraternal spirit.’”

What jump-started that brotherly love was the Spanish cubist’s distinctive 1914 collage, The Man at the Café.

The Man at the Café is the largest collage by Gris, and the only one to feature a human figure. Inspired by the fictional criminal mastermind Fantômas, popular in serial novels and silent films, Gris humorously captured a shady character hiding his face, his fedora casting an ominous shadow. The newspaper article, cut and pasted from Le Matin, reads, “One will no longer be able to make fake works of art,” although Gris himself attempted to trick the eye with the wood-grain paneling of the café interior.

In Cornell’s Homage to Juan Gris four decades later, “the black cutout, though split midway (a classic Gris maneuver), becomes more bottle than bird. As in many of the boxes [in the series], a real piece of wood serves as the bird’s perch, which sits, Cubist style, on a round table indicated by the wood-grain printed paper.”

You can find other works from the series here.

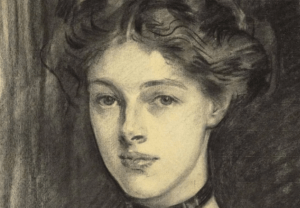

Also at The Met were Golden Kingdoms: Luxury and Legacy in the Ancient Americas, which was quite exhaustive, and Quicksilver Brilliance: Adolf de Meyer Photographs, which was quite fantastic.

A member of the “international set” in fin-de-siècle Europe, Baron Adolf de Meyer (1868–1946) was also a pioneering photographer, known for creating works that transformed reality into a beautiful fantasy. Quicksilver Brilliance is the first museum exhibition devoted to the artist in more than twenty years and the first ever at The Met. Some forty works, drawn entirely from The Met collection, demonstrate the impressive breadth of his career.

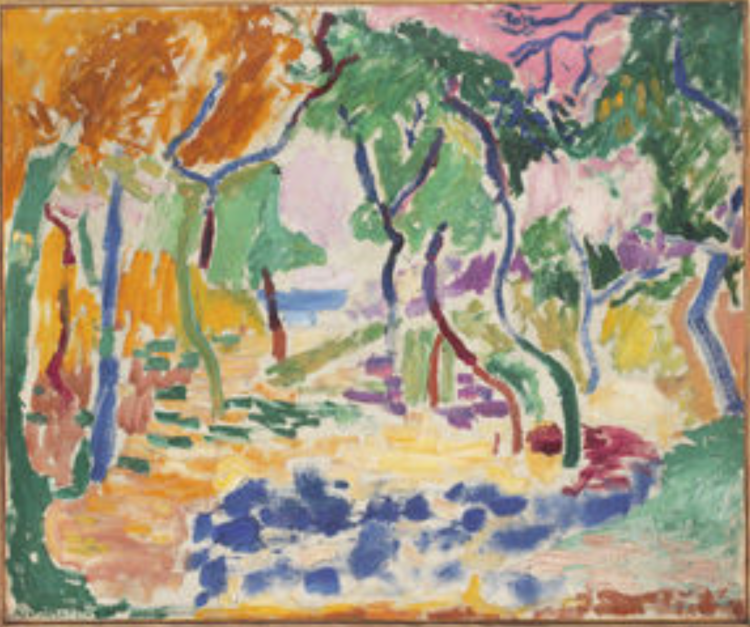

Public Parks, Private Gardens: Paris to Provence provided a placid finish to our Met meander.

Drawn from seven curatorial departments at The Met and supplemented by a selection of private collection loans, Public Parks, Private Gardens: Paris to Provence features some 150 works by more than 70 artists, spanning the late eighteenth through early twentieth century. Anchored by Impressionist scenes of outdoor leisure, the presentation offers a fresh, multisided perspective on best-known and hidden treasures housed in a Museum that took root in a park: namely, New York’s Central Park, which was designed in the spirit of Parisian public parks of the same period.

Those works in the exhibit included Claude Monet’s capture of Parc Monceau, one of our favorite spots in Paris.

On the way back to Boston we swung by Hartford’s Wadsworth Atheneum to catch Gorey’s Worlds, which was “centered on his personal art collection, which he chose to bequeath to the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, the only public institution to receive his legacy.”

The collection was personal, all right, and entirely peculiar, as you would expect. Just as Gorey “frequently stopped in Hartford when traveling between the city and his Cape Cod house in Yarmouth Port,” the Missus and I also frequently found the Wadsworth Atheneum a welcome pit stop as we wended our way homeward.

• • • • • • •

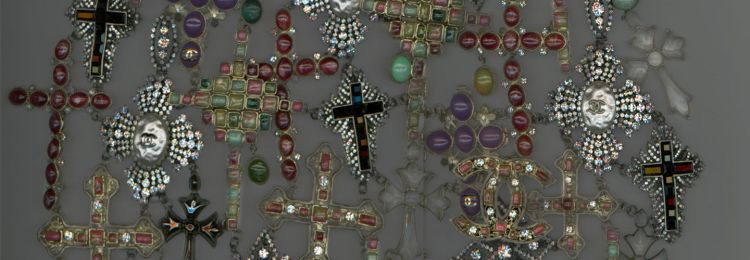

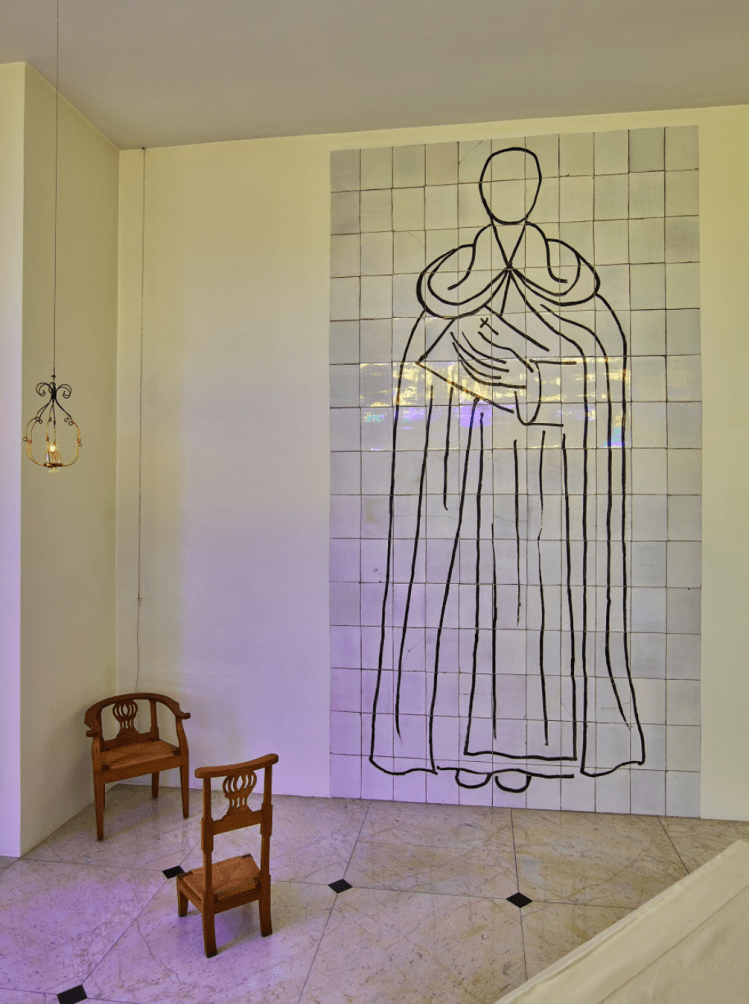

When we returned to the city in September, the main event was Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination at The Met.

The Costume Institute’s spring 2018 exhibition—at The Met Fifth Avenue and The Met Cloisters—features a dialogue between fashion and medieval art from The Met collection to examine fashion’s ongoing engagement with the devotional practices and traditions of Catholicism.

Serving as the cornerstone of the exhibition, papal robes and accessories from the Sistine Chapel sacristy, many of which have never been seen outside The Vatican, are on view in the Anna Wintour Costume Center. Fashions from the early twentieth century to the present are shown in the Byzantine and medieval galleries, part of the Robert Lehman Wing, and at The Met Cloisters.

In other words, all over the place.

The Met’s time-lapse video of the show’s installation is lots of fun, while this video provides a good overview of the exhibit.

As the Missus said, one of the best things about the exhibition was that it made us look more closely at the amazing work in the medieval gallery, a place we normally breeze through on the way to The Met cafeteria.

Unfortunately, we couldn’t say the same for many of the other works because their display was too, well, elevated. In a review of the exhibit on her CultureGrrl blog, Lee Rosenbaum wrote, “no one can properly see the fashion designers’ intricate creations, installed high above eye level for dramatic effect and to facilitate visitor flow. The sprawling installation, in multiple galleries at both the Met Fifth Avenue and the Cloisters, is a neck-craning experience . . .”

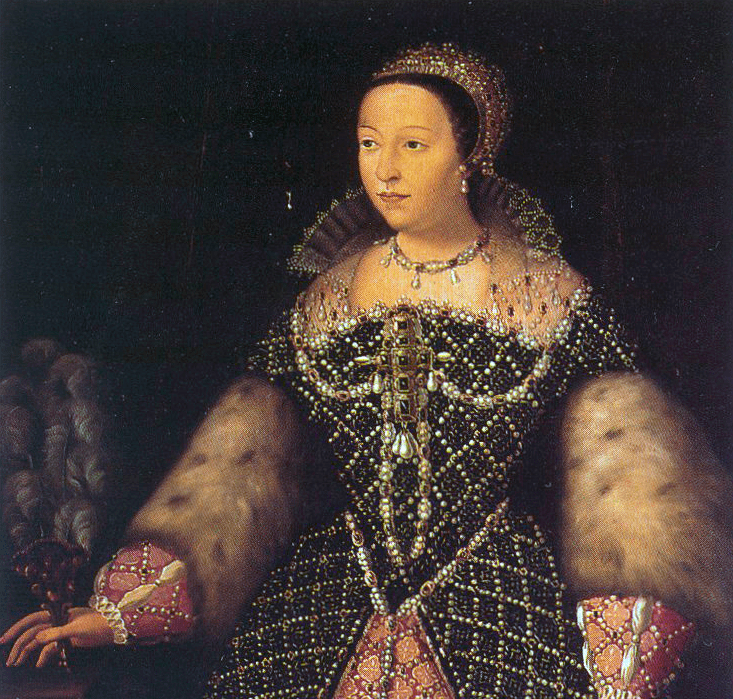

True enough. More down-to-earth, though, was the exhibit Visitors to Versailles.

Bringing together works from The Met, the Château de Versailles, and over fifty lenders, this exhibition highlights the experiences of travelers from 1682, when Louis XIV moved his court to Versailles, to 1789, when the royal family was forced to leave the palace and return to Paris. Through paintings, portraits, furniture, tapestries, carpets, costumes, porcelain, sculpture, arms and armor, and guidebooks, the exhibition illustrates what visitors encountered at court, what kind of welcome and access to the palace they received, and, most importantly, what impressions, gifts, and souvenirs they took home with them.

Most of the exhibit was, as the barkers say about every artwork at Paris bazaars, très jolie, très très charmante, avec beaucoup d’atmosphere.

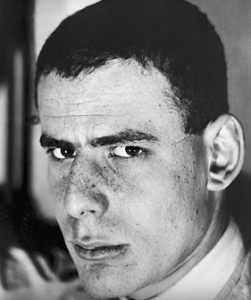

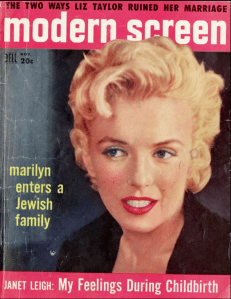

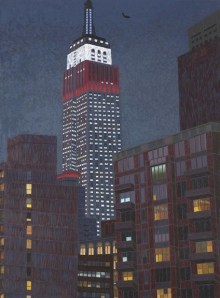

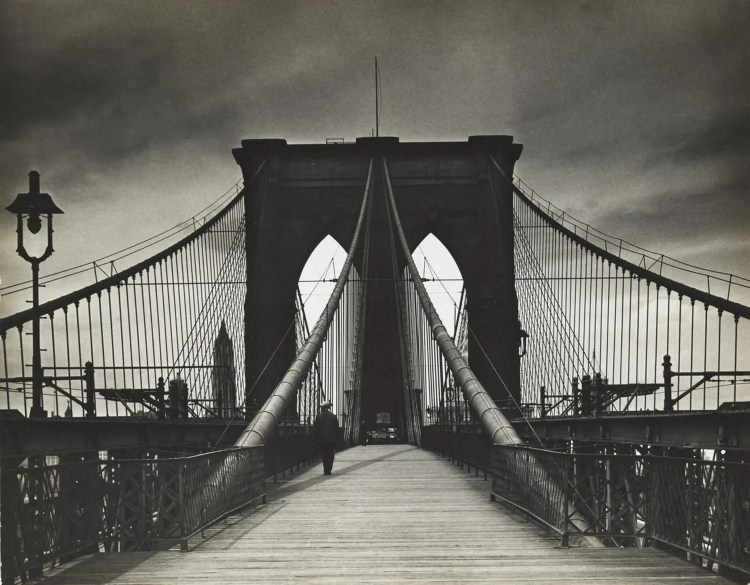

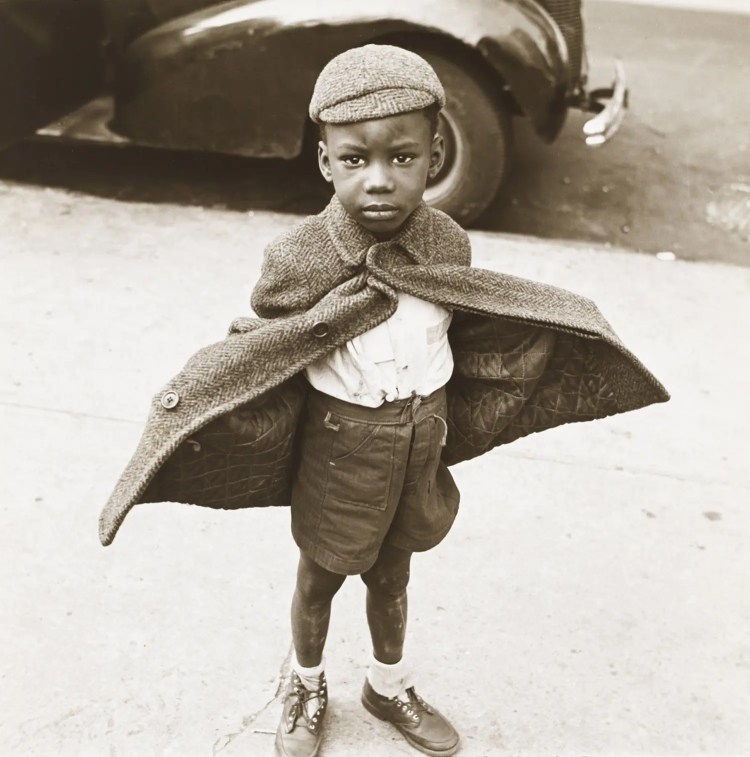

From there we moseyed up to the Museum of the City of New York to view Through a Different Lens: Stanley Kubrick Photographs.

Stanley Kubrick was just 17 when he sold his first photograph to the pictorial magazine Look in 1945. In his photographs, many unpublished, Kubrick trained the camera on his native city, drawing inspiration from the nightclubs, street scenes, and sporting events that made up his first assignments, and capturing the pathos of ordinary life with a sophistication that belied his young age. Through a Different Lens: Stanley Kubrick Photographs features more than 120 photographs by Kubrick from the Museum’s Look magazine archive, along with vintage Look magazines in which many of the photographs were published. Through a Different Lens evokes the grit, glamor, and resilience of New York City, while telling the story of how a young amateur photographer from the Bronx took his first steps toward becoming one of the most important and influential film directors of the twentieth century.

The exhibit highlights a number of other stories as well.

There’s a great anecdote about Kubrick Riding the Subway.

“I wanted to retain the mood of the subway, so I used natural light,” he said. People who ride the subway late at night are less inhibited than those who ride by day. Couples make love openly, drunks sleep on the floor and other unusual activities take place late at night. To make pictures in the off-guard manner he wanted to, Kubrick rode the subway for two weeks. Half of his riding was done between midnight and six a.m. Regardless of what he saw he couldn’t shoot until the car stopped in a station because of the motion and vibration of the moving train. Often, just as he was ready to shoot, someone walked in front of the camera, or his subject left the train.

Kubrick finally did get his pictures, and no one but a subway guard seemed to mind. The guard demanded to know what was going on. Kubrick told him

“Have you got permission?” the guard asked.

“I’m from LOOK,” Kubrick answered.

“Yeah, sonny,” was the guard’s reply, “and I’m the society editor of the Daily Worker.”

From there we hoofed it down to the Met Breuer, although in the end we sort of wished we hadn’t. The main exhibit was Like Life: Sculpture, Color, and the Body, which purported to “explores narratives of sculpture in which artists have sought to replicate the literal, living presence of the human body,” but was just kind of bizarre and creepy. Obsessions: Nudes by Klimt, Schiele, and Picasso, on the other hand, was just meh.

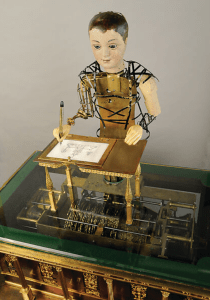

So we shuttled crosstown to the New-York Historical Society, whose numerous attractions started with Summer of Magic: Treasures from the David Copperfield Collection , which included “iconic objects used by Harry Houdini, and . . . the Death Saw from one of Copperfield’s most famous illusions!”

Also quite magical was the newly installed Gallery of Tiffany Lamps, an exhibit that is totally eye-popping.

As the centerpiece of the 4th floor, the Gallery of Tiffany Lamps features 100 illuminated Tiffany lamps from our spectacular collection, displayed within a dramatically lit jewel-like space. Regarded as one of the world’s largest and most encyclopedic, the Museum’s Tiffany Lamp collection includes multiple examples of the Dragonfly shade, a unique Dogwood floor lamp (ca. 1900–06), a Wisteria table lamp (ca. 1901), and a rare, elaborate Cobweb shade on a Narcissus mosaic base (ca. 1902), among many others.

The hidden history behind the lamps offers a fascinating look at the contributions of women

in the creation of this art. Louis C. Tiffany (1848–1933) was the artistic genius behind Tiffany Studios. However, he was not the exclusive designer of its lamps, windows, and luxury objects: Clara Driscoll (1861–1944), head of the Women’s Glass Cutting Department from 1892 to 1909, has recently been revealed as the designer of many of the firm’s leaded glass shades. Driscoll and her staff, self-styled the “Tiffany Girls,” labored in anonymity but were well compensated. Driscoll’s weekly salary of $35 was on par with that of Tiffany’s male designers, a reflection of his regard for her abilities. The lamps in this exhibition reflect the prodigious talent of designers and artisans who worked in anonymity to fulfill Tiffany’s aesthetic vision.

in the creation of this art. Louis C. Tiffany (1848–1933) was the artistic genius behind Tiffany Studios. However, he was not the exclusive designer of its lamps, windows, and luxury objects: Clara Driscoll (1861–1944), head of the Women’s Glass Cutting Department from 1892 to 1909, has recently been revealed as the designer of many of the firm’s leaded glass shades. Driscoll and her staff, self-styled the “Tiffany Girls,” labored in anonymity but were well compensated. Driscoll’s weekly salary of $35 was on par with that of Tiffany’s male designers, a reflection of his regard for her abilities. The lamps in this exhibition reflect the prodigious talent of designers and artisans who worked in anonymity to fulfill Tiffany’s aesthetic vision.Also at NYHS: an exhibit Celebrating Bill Cunningham, the legendary New York Times photographer, and a kicky Walk This Way: Footwear from the Stuart Weitzman Collection of Historic Shoes.

Then we walked back to our hotel.

The next morning we started at The Morgan Library & Museum, which featured The Magic of Handwriting: The Pedro Corrêa do Lago Collection.

For nearly half a century, Brazilian author and publisher Pedro Corrêa do Lago has been assembling one of the most comprehensive autograph collections of our age, acquiring thousands of handwritten letters, manuscripts, and musical compositions as well as inscribed photographs, drawings, and documents. This exhibition—the first to be drawn from his extraordinary collection—features some 140 items, including letters by Lucrezia Borgia, Vincent van Gogh, and Emily Dickinson, annotated sketches by Michelangelo, Jean Cocteau, and Charlie Chaplin, and manuscripts by Giacomo Puccini, Jorge Luis Borges, and Marcel Proust.

Here’s a totally engrossing video about the exhibit.

It was great to be there so early – the place was empty and quiet and we got to read almost all the manuscripts in Corrêa do Lago’s staggering collection.

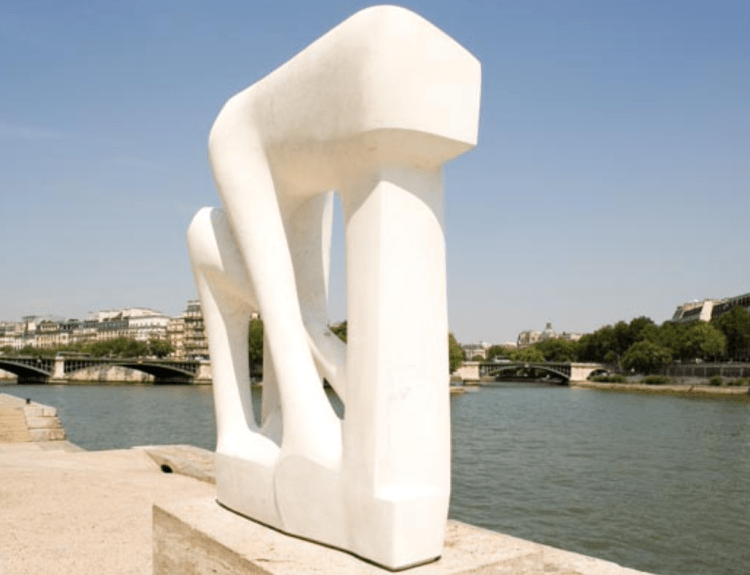

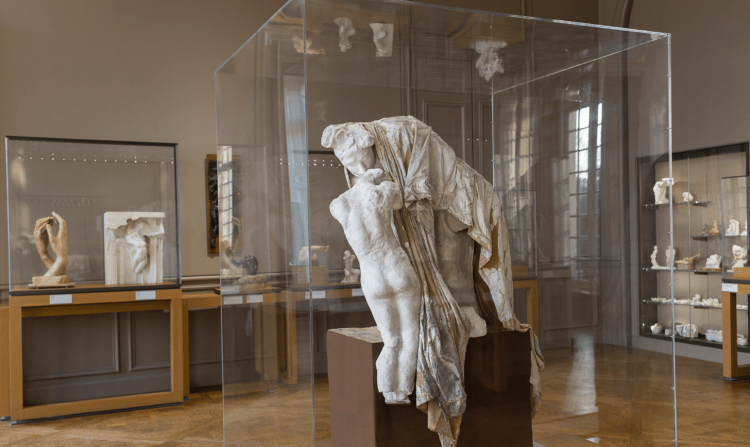

From there we drifted up to MoMA to catch Constantin Brâncuși Sculpture, which “celebrates MoMA’s extraordinary holdings—11 sculptures by Brâncuși will be shown together for the first time, alongside drawings, photographs, and films.” Extraordinarily swell.

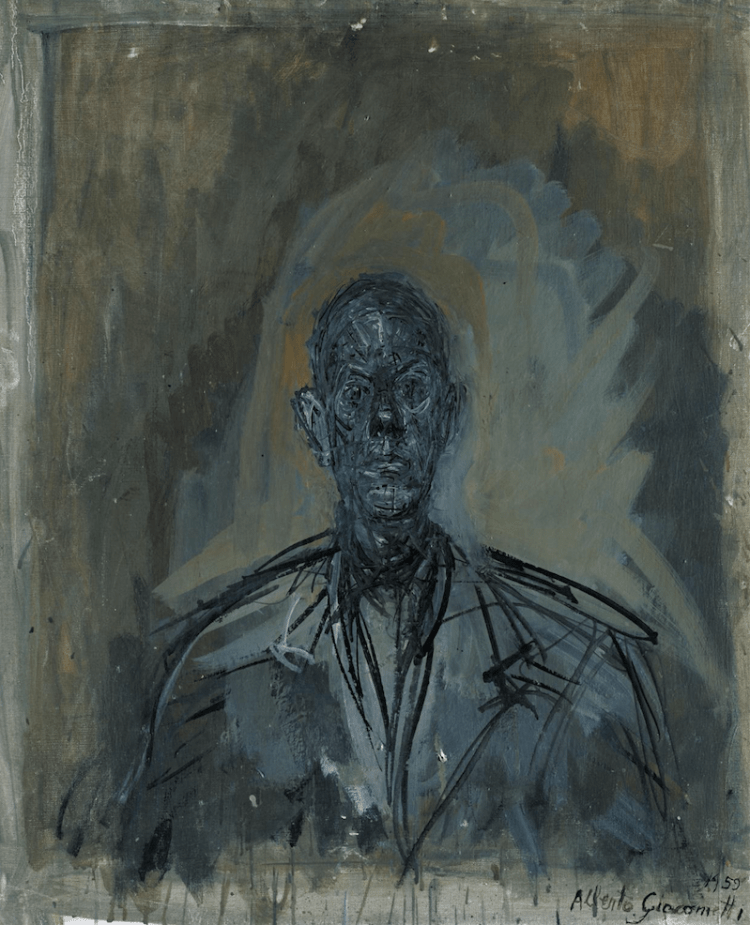

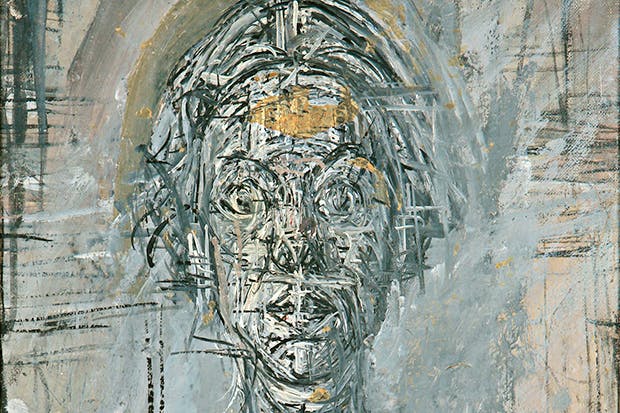

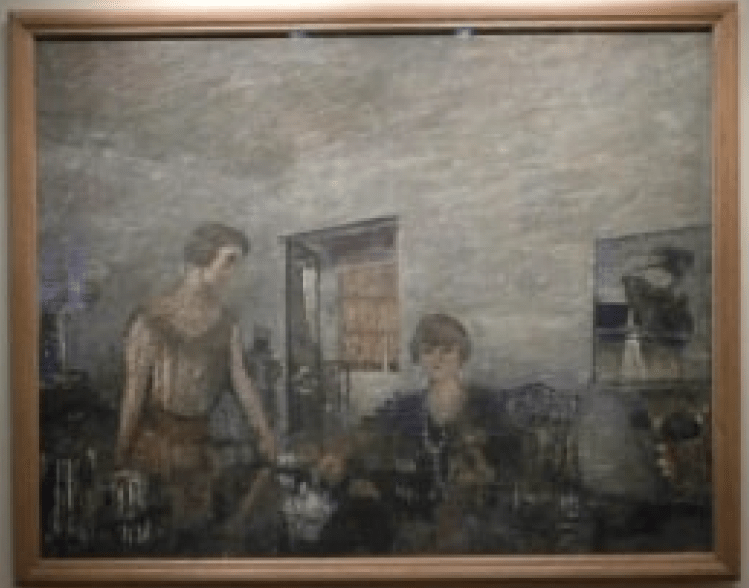

As was the Guggenheim’s exhibit of fellow sculptor Alberto Giacometti.

A preeminent artist of the twentieth century, Alberto Giacometti (1901–1966) investigated the human figure for more than forty years. This comprehensive exhibition, a collaboration with the Fondation Giacometti in Paris, examines anew the artist’s practice and his unmistakable aesthetic vocabulary. Featuring important works in bronze and in oil, as well as plaster sculptures and drawings never before seen in this country, the exhibition aims to provide a deeper understanding of this artist, whose intensive focus on the human condition continues to provoke and inspire new generations.

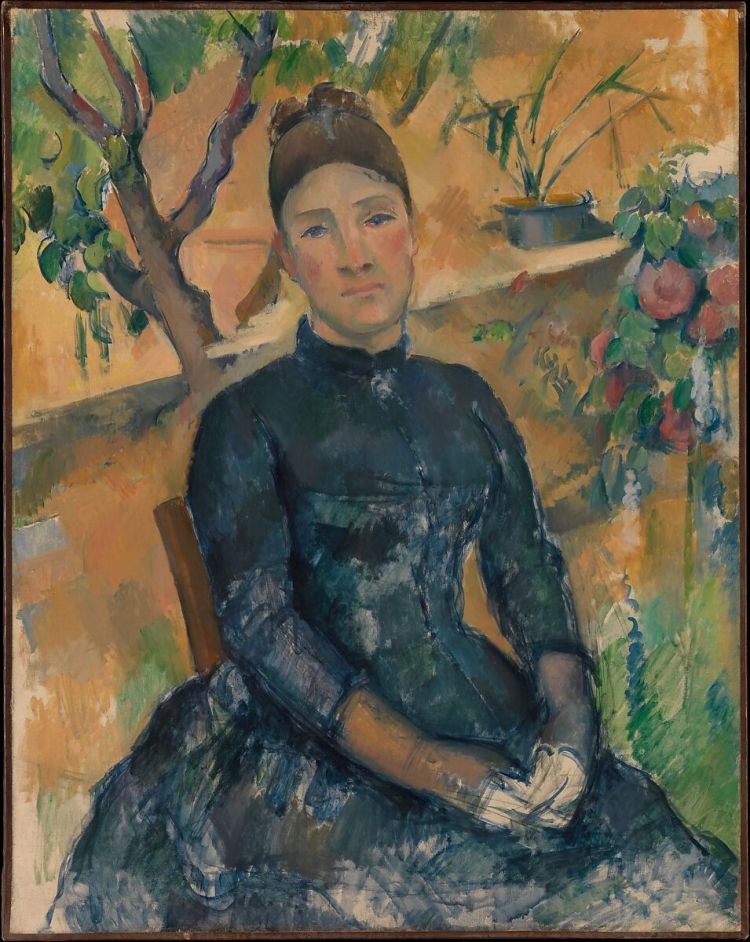

Giacometti’s paintings are just as engrossing as his sculpture, from his long-sitting brother Diego . . .

. . . to his long-suffering wife Annette.

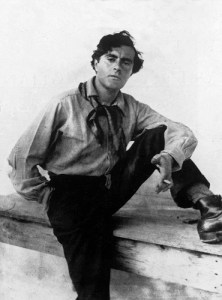

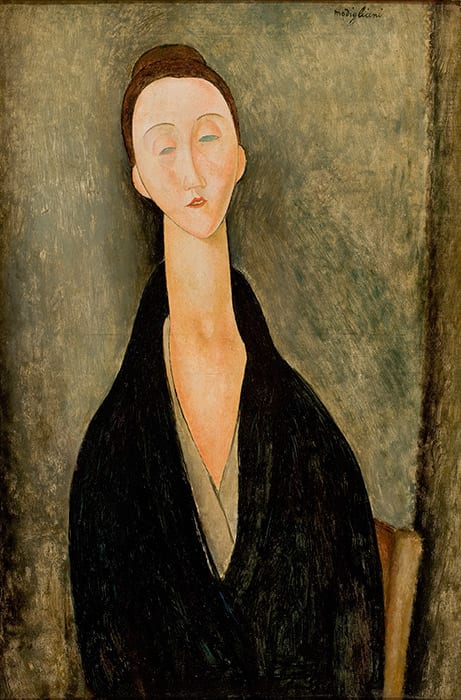

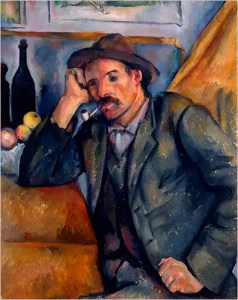

It was art of a different color at The Jewish Museum, which showcased Chaim Soutine: Flesh.

Chaim Soutine (1893–1943) is one of the twentieth century’s great painters of still life. In the Paris of the 1920s, Soutine was a double outsider—an immigrant Jew and a modernist. Guided by his expressive artistic instincts, he both embraced the traditional genre of still life and exploded it . . .

Soutine’s harsh and wrenching portrayals—of beef carcasses, plucked fowl, fish, and game—create a parallel between the animal and human, between beauty and pain. His still-life paintings, produced over a period of thirty years, express with visceral power his painterly mastery and personal passion.

The exhibit didn’t exactly make us hungry, but the Missus and I grabbed a quick dinner anyway and headed down to the Second Stage Theater production of Young Jean Lee’s Straight White Men at the Helen Hayes Theater. The play itself was smart enough, but the deafening pre-show music – “loud hip-hop with sexually explicit lyrics by female rappers” – was less so, designed by the playwright to make the audience feel as uncomfortable as the LGBTQ+ community commonly feels.

A whole bunch of the audience, however, did not want to hear it.

On our way back to Boston the next day, the Missus and I swung by The Met Cloisters to catch the other half of Heavenly Bodies and, given the setting, it was even more effective (and far less crowded) than the show at the mothership.

Then we took our bodies home.

• • • • • • •

Whether by dumb luck or the hand of providence, the Missus and I ventured to the Big Town four times in 2019, the last full year of the Before Times.

Our March trip kicked off with a subway ride from our hotel on 32nd Street to Lincoln Center and The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, where Voice of My City: Jerome Robbins and New York was on display, “[tracing] Robbins’ life and dances alongside the history of New York, inspiring viewers to see the city as both a muse and a home.”

This virtual tour from Playbill is well worth taking.

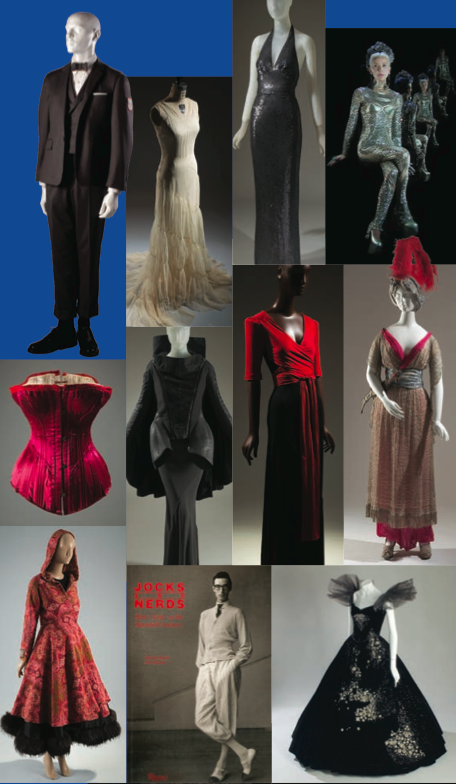

After that we headed back downtown to the Fashion Institute of Technology, which had mounted Exhibitionism: 50 Years of The Museum at FIT.

Exhibitionism: 50 Years of The Museum at FIT celebrates the 50th anniversary of what Michael Kors calls “the fashion insider’s fashion museum” by bringing back 33 of the most influential exhibitions produced since the first one was staged in 1971. Taken entirely from the museum’s permanent holdings, more than 80 looks are on display. From Fashion and Surrealism to The Corset to A Queer History of Fashion, the exhibitions are known for being “intelligent, innovative, and independent,” says MFIT Director Valerie Steele. “The museum has been in the forefront of fashion curation, with more than 200 fashion exhibitions over the past half century, many accompanied by scholarly books and symposia.”

Our favorite in the shoe department.

Kicky, no?

As we hoofed it out of FIT, we spotted this across 27th Street in FIT’s Art and Design Gallery.

This special short exhibition, curated by Communication Design Pathways Professor Anne Kong and 42 students in the Visual Presentation and Exhibition Design program, features hats from the celebrated collection of the late former FIT dean and professor Nina Kurtis.

The students designed and created individual 360-degree displays featuring a hat from a distinctive time period or fashion trend using visual storytelling to entertain and educate the viewer. The displays incorporate various materials, handmade props, and mannequin parts.

The hats were a hoot, as “Jackie” stylishly illustrates.

That topped off our evening rather nicely.

The next morning it was off to the Museum of Modern Art to view Joan Miró: Birth of the World.

“You and all my writer friends have given me much help and improved my understanding of many things,” Joan Miró told the French poet Michel Leiris in the summer of 1924, writing from his family’s farm in Montroig, a small village nestled between the mountains and the sea in his native Catalonia. The next year, Miró’s intense engagement with poetry, the creative process, and material experimentation inspired him to paint The Birth of the World.

In this signature work, Miró covered the ground of the oversize canvas by applying paint in an astonishing variety of ways that recall poetic chance procedures. He then added a series of pictographic signs that seem less painted than drawn, transforming the broken syntax, constellated space, and dreamlike imagery of avant-garde poetry into a radiantly imaginative and highly inventive form of painting. He would later describe this work as “a sort of genesis,” and his Surrealist poet friends titled it The Birth of the World.

The exhibit also featured this monumental mural.

A story goes with it: The mural was commissioned in 1950 for Harvard University’s new Graduate Student Center by Walter Gropius, the Department of Architecture chair and founder of Germany’s Bauhaus School in 1919. After Miró delivered it, the mural was hung in the Grad Center . . . over a radiator, which during the next few years started to sort of melt the artwork.

So Miró said, hey – send it back and I’ll fix it. And the fix was certainly in: Miró returned a ceramic tile version of the mural to Harvard (which is still there), then touched up the original mural and sold it to MoMA for a pretty penny.

But – consolation prize! – Harvard also has Miró’s original sketch for the mural, which the Harvard Art Museums displayed in its 2019 exhibit, The Bauhaus and Harvard.

That mural traveled more than just Cambridge to New York, yeah?

From MoMA we headed down to SoHo and the Center for Italian Modern Art to see Metaphysical Masterpieces 1916-1920: Morandi, Sironi, and Carrà.

The term “metaphysical painting” (pittura metafisica) refers to an artistic style that emerged in Italy during the First World War. Closely associated with [Giorgio] de Chirico, it often featured disquieting images of eerie spaces and enigmatic objects, eliciting a sense of the mysterious. Metaphysical Masterpieces concentrates on rarely seen early works by Giorgio Morandi and important paintings by the lesser- known artists Carlo Carrà and Mario Sironi, offering a richer and more nuanced view of pittura metafisica than previous exhibitions in the United States, creating a vivid portrait of the genre.

Representative samples from Morandi and Sironi.

The exhibit was excellent and the people there were lovely – they gave me and the Missus a wonderfully informative tour and even made espresso for us. Molte grazie!

Sadly, the Center for Italian Modern Art is no more, victim of a challenging economic climate, as Zachary Small reported in the New York Times.

Laura Mattioli, founder of the Center for Italian Modern Art, said that recent financial challenges had led to the decision to close.

“We were open for about 11 years, but the situation has changed since the pandemic,” said Mattioli, who has an apartment in the same Broome Street building as the museum. “We sometimes spent more on the travel of artworks to and from Italy than the actual value of the artworks themselves.”

Beyond that, Mattioli told the Times, “after the pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement . . . many grant-making organizations appeared to require that exhibition proposals include elements of diversity and inclusion” – something not exactly prevalent in modern Italian art.

Our loss, sì?

Back in the Big Town, we subwayed to the Brooklyn Museum for the much-hyped Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving.

Mexican artist Frida Kahlo’s unique and immediately recognizable style was an integral part of

her identity. Kahlo came to define herself through her ethnicity, disability, and politics, all of which were at the heart of her work. Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving is the largest U.S. exhibition in ten years devoted to the iconic painter and the first in the United States to display a collection of her clothing and other personal possessions, which were rediscovered and inventoried in 2004 after being locked away since Kahlo’s death, in 1954.

her identity. Kahlo came to define herself through her ethnicity, disability, and politics, all of which were at the heart of her work. Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving is the largest U.S. exhibition in ten years devoted to the iconic painter and the first in the United States to display a collection of her clothing and other personal possessions, which were rediscovered and inventoried in 2004 after being locked away since Kahlo’s death, in 1954.There was lots of clothing, photos, jewelry, and assorted other Fridabilia – but not all that much artwork. The whole exhibit seemed more about Kahlo as celebrity/cult figure than anything else. That’s certainly what the Selfie Set was most interested in, to all appearances.

(Luckily, a better sense of Kahlo as an artist was on display at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts at the time. Frida Kahlo and Arte Populaire explored “how her passion for objects such as decorated ceramics, embroidered textiles, children’s toys, and devotional retablo paintings shaped her own artistic practice.” It was more interesting than the Brooklyn show, even if a bit less selfie-satisfied.)

The next morning we cruised up Madison Avenue with nary a red light for fifty blocks (as opposed to Boston’s traffic lights, which seem to have been timed by Joe Cocker), turned onto 84th Street, and found a spot right in front of my old grammar school, St. Ignatius Loyola, which is operated by the Sisters of (Parking) Charity.

From there we sashayed up to The Met for Epic Abstraction: Pollock to Herrera, which began with a quote from AbEx pioneer Barnett Newman.

We felt the moral crisis of a world in shambles, a world devastated by a great depression and a fierce world war, and it was impossible at that time to paint the kind of painting that we were doing—flowers, reclining nudes, and people playing the cello. . . . So we actually began, so to speak, from scratch, as if painting were not only dead but had never existed.

You can see most of the exhibition objects here, but these highlights will give you a sense of the collection overall.

Willem de Kooning, Easter Monday (1955-56).

Louise Nevelson, Mrs. N’s Palace (1964-77).

Barnett Newman, Shimmer Bright (1968).

Although the exhibit is long gone, many of the works remain on view in Galleries 917–925 at The Met.

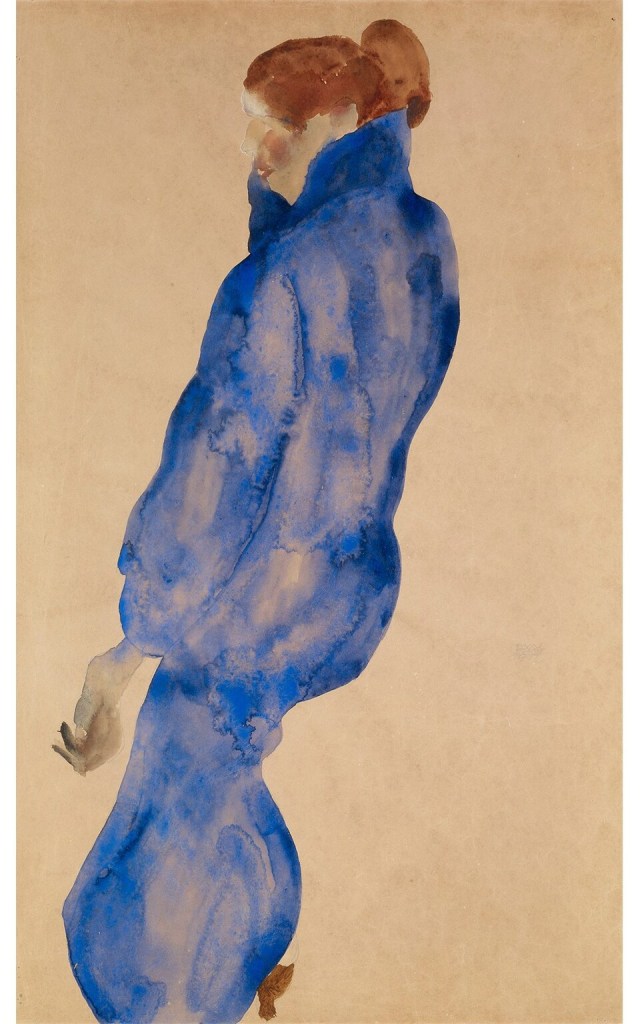

After a costly lunch in the Met cafeteria (where we watched two young women pour two glasses of wine – one red, one white – arrange them just so, and Instagram them to the world at large), we moseyed up to the Neue Galerie for The Self-Portrait, from Schiele to Beckmann.

“The Self-Portrait, from Schiele to Beckmann” is an unprecedented exhibition that examines works primarily from Austria and Germany made between 1900 and 1945. This groundbreaking show is unique in its examination and focus on works of this period. Approximately 70 self-portraits by more than 30 artists—both well-known figures and others who deserve greater recognition—will be united in the presentation, which is comprised of loans from public and private collections worldwide . . .

Some of the most outstanding self-portraits in this exhibition are by women, including Paula Modersohn-Becker, who painted a number of bold, groundbreaking self-portraits, some of which highlighted her pregnancy; and Käthe Kollwitz, who cast an unsparing eye on her own world-weary visage. The best of these works always engage the viewer in a complex and meaningful way.

Some other autoportraits from those madcap German Expressionists.

With that, we headed back to face the stop-and-go-and-stop traffic of Boston.

• • • • • • •

Upon our return to the city in June, the Missus and I first visited, as we often did, The Museum at FIT, where Minimalism/Maximalism (“the first exhibition devoted to the historical interplay of minimalist and maximalist aesthetics as expressed through high fashion”) was on display, although in fairness it should really have been called Artful/Awful.

The former, from Narcisco Rodriguez in 2011.

The latter, from Comme des Garçons in 2018.

That’s just so . . . ongepotchket.

From there we drifted past Bryant Park and – lucky us – stumbled upon Yoga Night!, which urged us to “perfect your downward dog at our outdoor yoga classes.” We did not, for those of you keeping score at home.

Instead, we wandered over to the Manhattan Theatre Club’s Samuel J. Friedman Theatre for the Almeida Theatre production of James Graham’s Ink.

It’s 1969 London. The brash young Rupert Murdoch (Tony winner Bertie Carvel) purchases a struggling paper, The Sun, and sets out to make it a must-read smash which will destroy – and ultimately horrify – the competition. He brings on rogue editor Larry Lamb (Olivier winner Jonny Lee Miller) who in turn recruits an unlikely team of underdog reporters. Together, they will go to any lengths for success and the race for the most ink is on!

It’s 1969 London. The brash young Rupert Murdoch (Tony winner Bertie Carvel) purchases a struggling paper, The Sun, and sets out to make it a must-read smash which will destroy – and ultimately horrify – the competition. He brings on rogue editor Larry Lamb (Olivier winner Jonny Lee Miller) who in turn recruits an unlikely team of underdog reporters. Together, they will go to any lengths for success and the race for the most ink is on! Larry Lamb is tasked by Rupert Murdoch with overtaking – in one year – The Mirror, which has the largest circulation in the U.K. (four million daily), while The Sun’s circulation is among the smallest.

The production was loud, manic, and fabulously staged, with terrific performances by the lead actors.

Here’s a clip about the Theme Weeks that The Sun relentlessly promoted to boost readership. It’s a hoot.

The play wasn’t just smart – it was prescient. The Sun was determined to be a disruptor, giving voice to the people and relying on them for content, which the paper now describes this way.

From the beginning, it was clear Sun readers were not content to sit on the sidelines and be lectured to. They wanted to get involved.

Whether fighting injustice, dashing off an opinion to our Letters page, sharing a shopping tip or entering competitions, our army of readers has always been as much a part of the fabric of the paper as the journalists who put it together.

And that was well before social media took over.

An Australian woman was sitting behind us, decrying how Rupert Murdoch has been so destructive to democracy the world over. But she failed to recognize the creative Murdoch – the one who has seen the gaps in the media world that he could fill with The Sun, the Fox Broadcast Network, the Fox News Channel.

The mistake people make is in thinking Rupert Murdoch has some set of bedrock conservative principles. Not even close. He’s only interested in principal – how much money he can make exploiting the public’s basest instincts, which are fear, hatred, and rage.

And that’s what Ink so deftly illustrated.

The next morning it was off to the Museum of Modern Art – which was closing after that weekend to undertake a four-month $450 million expansion – for Lincoln Kirstein’s Modern.

“I have a live eye,” proclaimed Lincoln Kirstein, signaling his wide-ranging vision. Lincoln Kirstein’s Modern explores this polymath’s sweeping contributions to American cultural life

in the 1930s and ’40s. Best known for cofounding New York City Ballet and the School of American Ballet with George Balanchine, Kirstein (1907–1996), a writer, critic, curator, impresario, and tastemaker, was also a key figure in MoMA’s early history. With his prescient belief in the role of dance within the museum, his championing of figuration in the face of prevailing abstraction, and his position at the center of a New York network of queer artists, intimates, and collaborators, Kirstein’s impact remains profoundly resonant today.

in the 1930s and ’40s. Best known for cofounding New York City Ballet and the School of American Ballet with George Balanchine, Kirstein (1907–1996), a writer, critic, curator, impresario, and tastemaker, was also a key figure in MoMA’s early history. With his prescient belief in the role of dance within the museum, his championing of figuration in the face of prevailing abstraction, and his position at the center of a New York network of queer artists, intimates, and collaborators, Kirstein’s impact remains profoundly resonant today.Not to mention Kirstein’s being a major enabler of Nazi-sympathizing starchitect Philip Johnson, which MoMA actually did not mention, to its discredit.

Here’s MoMA’s video, if you’re still interested. And here are the images in the exhibit. For me and the Missus, the best parts of the show were the artworks Kirstein himself collected, such as Elie Nadelman’s Man in the Open Air.

Over all, a decent presentation of a not-so-decent guy.

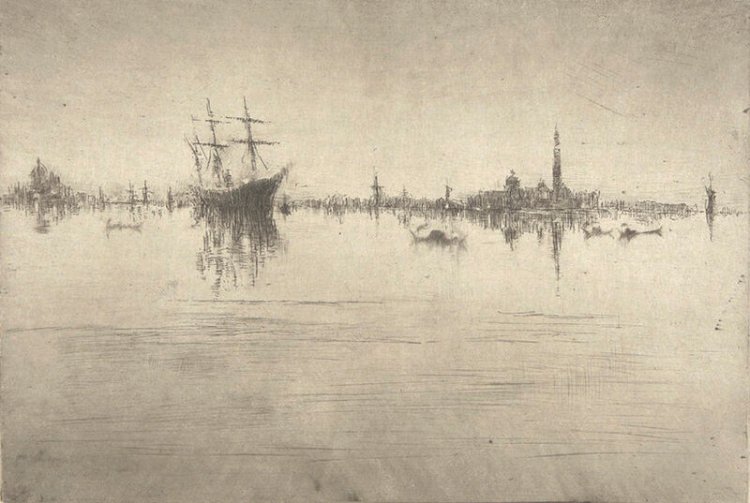

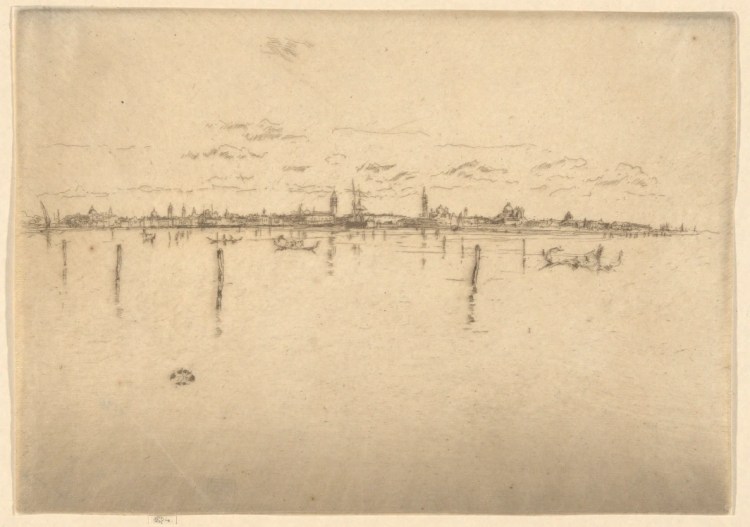

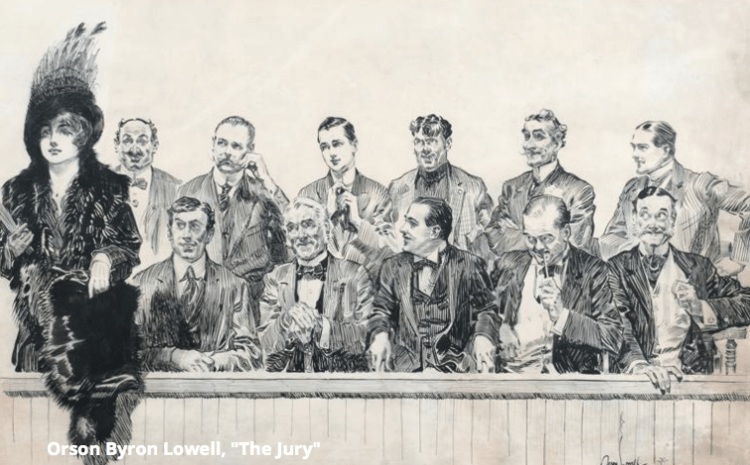

Next up: The Frick Collection, which was planning a four year renovation of its own, with an interim residence at the Breuer Building (which The Met would very helpfully be vacating). In addition to the sheer pleasure of wandering through Frick’s old pad, there was Whistler as Printmaker: Highlights from the Gertrude Kosovsky Collection.

The Frick Collection was pleased to announce a promised gift of forty-two works on paper by James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903), from the collection of Gertrude Kosovsky. An exhibition highlighting fifteen prints and one pastel from the gift is now on view in the Cabinet Gallery. The collection was formed over five decades by Mrs. Kosovsky, with the support of her husband, Dr. Harry Kosovsky, and includes twenty-seven etchings, fourteen lithographs, and one pastel, which range from Whistler’s early etchings dating from the late 1850s to lithographs of the late 1890s. Most are impressions made during his lifetime, a number of them from his major published sets, while others were produced for periodicals, thus encompassing different aspects of the American expatriate’s prolific activity as a printmaker.

The sixteen works from the exhibit are here, but it was a joy to see Whistler’s etchings up close, especially with the aid of the magnifying glasses the Frick thoughtfully provided.

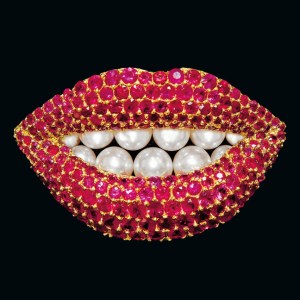

From the Frick we moseyed up Fifth Avenue to The Met, where the main attraction was Camp: Notes on Fashion.

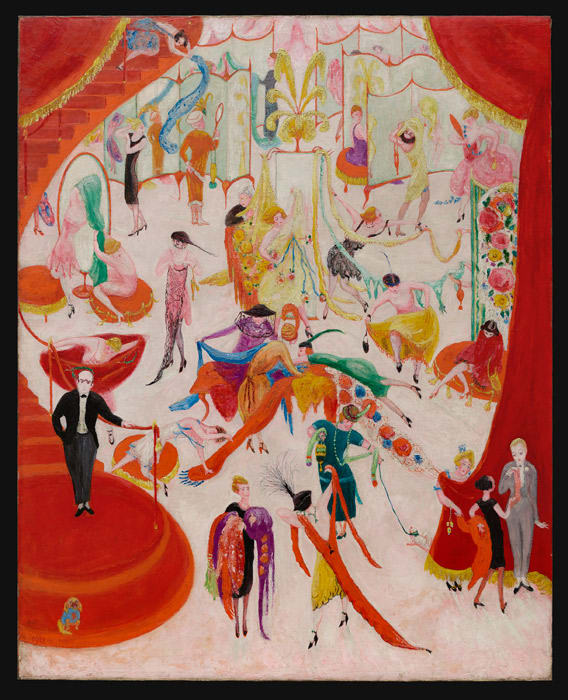

Through more than 250 objects dating from the seventeenth century to the present, The Costume Institute’s spring 2019 exhibition explores the origins of camp’s exuberant aesthetic. Susan Sontag’s 1964 essay “Notes on ‘Camp’” provides the framework for the exhibition, which examines how the elements of irony, humor, parody, pastiche, artifice, theatricality, and exaggeration are expressed in fashion.

Here’s Sontag’s essay (tip o’ the hat to UCLA’s Design Media Arts department). And here’s a guided tour of the exhibit.

Sontag said that “the essence of Camp is its love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration.” The Met exhibit seemed to say that Camp was whatever the curator wanted it to be. So the whole thing – audio, video, clothing, accessories, etc. – was a hot mess. Add to that the swarms of people taking selfies and barely looking at any one object for more than five seconds, and we quickly went from Camp to decamp.

While the Camp exhibit was a hot mess, Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock & Roll was just hot.

For the first time, a major museum exhibition examines the instruments of rock and roll. One of the most important artistic movements of the twentieth century, rock and roll’s seismic influence was felt across culture and society. Early rock musicians were attracted to the wail of the electric guitar and the distortion of early amplifiers, a sound that became forever associated with rock music and its defining voice. Rock fans have long been fascinated with the instruments used by musicians. Many have sought out and acquired the exact models of instruments and equipment used by their idols, and spent countless hours trying to emulate their music and their look. The instruments used in rock and roll had a profound impact on this art form that forever changed music.

You can see all the exhibit’s instruments here, from Keith Emerson’s customized Moog Synthesizer to Jimmy Page’s Black Beauty guitar that was stolen from a Minneapolis airport in 1970 and – amazingly – returned to him (the exhibit doesn’t say how) in 2015. A Whitman’s Sampler of videos can be found here. You are definitely encouraged to sample.

We did some other stuff on that trip, but nothing worth spending any more time on.

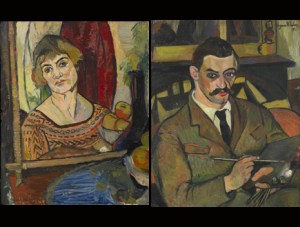

On the way home, however, we stopped by the Bruce Museum in Greenwich to see Summer with the Averys [Milton | Sally | March].

On May 11, 2019, the Bruce Museum [opened] Summer with the Averys [Milton | Sally | March]. Featuring landscapes, seascapes, beach scenes, and figural compositions—as well as rarely seen travel sketchbooks—the exhibition takes an innovative approach to the superb work produced by the Avery family. Along with canonical paintings by Milton Avery, the show offers a unique opportunity to become acquainted with the remarkable art created by Avery’s wife Sally and their daughter March.

Milton Avery, his wife Sally Michel, and their daughter March were inveterate summer travelers, with destinations including Mexico; Laguna Beach, California; Canada’s Gaspé Peninsula; Provincetown, Massachusetts; Woodstock, New York; the MacDowell Colony in New Hampshire; Yaddo in upstate New York; and Europe.

What the exhibit vividly displayed was not just the closeness of the family, but the familial resemblance of the art they produced.

Milton Avery (American, 1885-1965). Thoughtful Swimmer, 1943.

Sally Michel (American, 1902-2003). Swimming Lesson, 1987.

March Avery (American, b. 1932). The Dead Sea, 2009.

Just a lovely exhibit.

Before we left the museum, we checked out Sharks! Myths and Realities and learned this fun fact: More Americans are killed every year by ballpoint pens and vending machines than by sharks.

You could look it up.

• • • • • • •

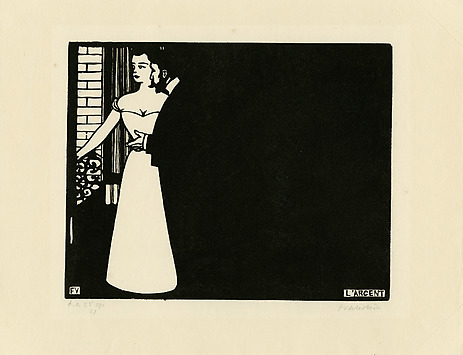

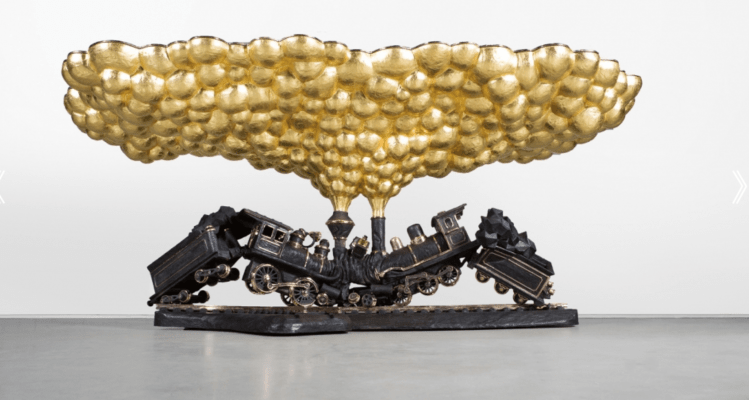

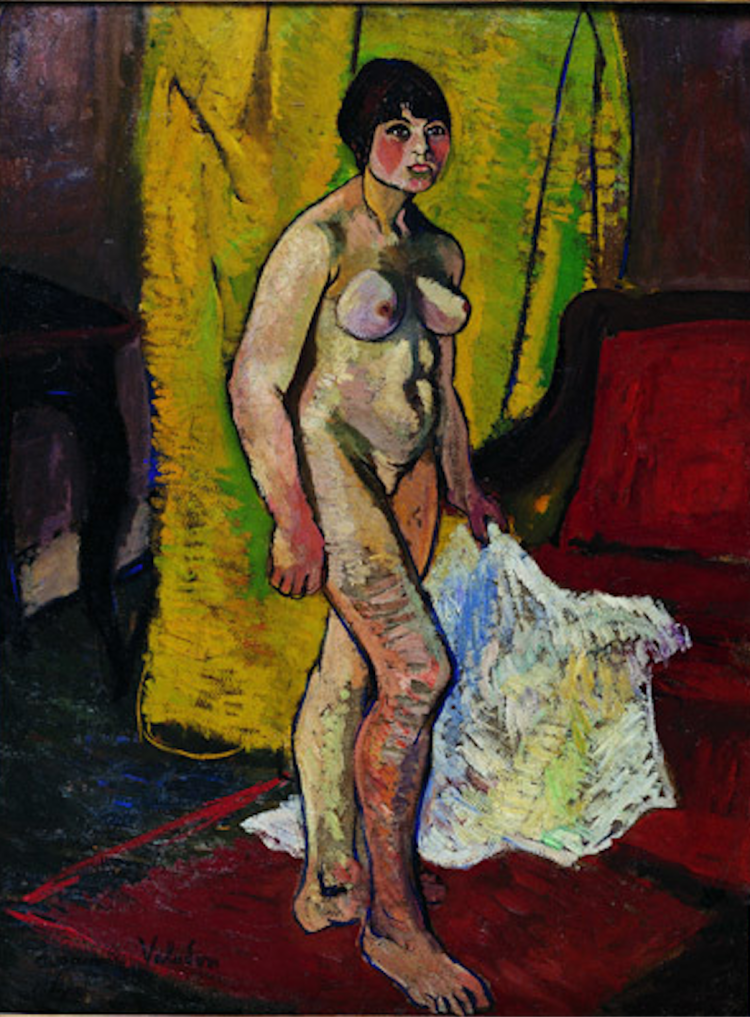

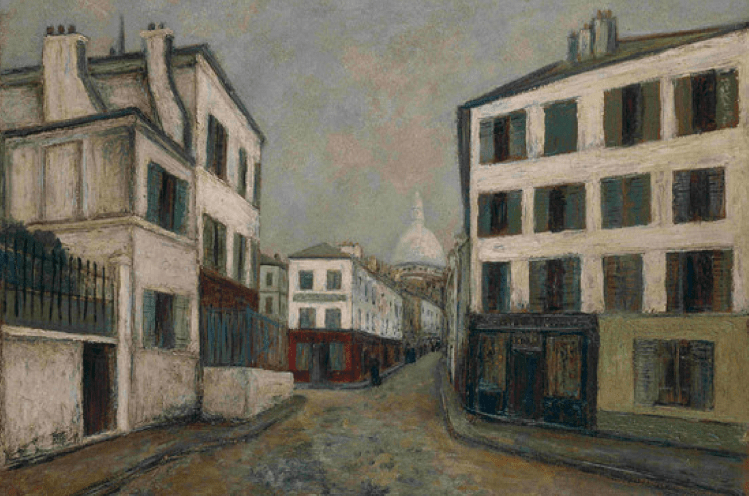

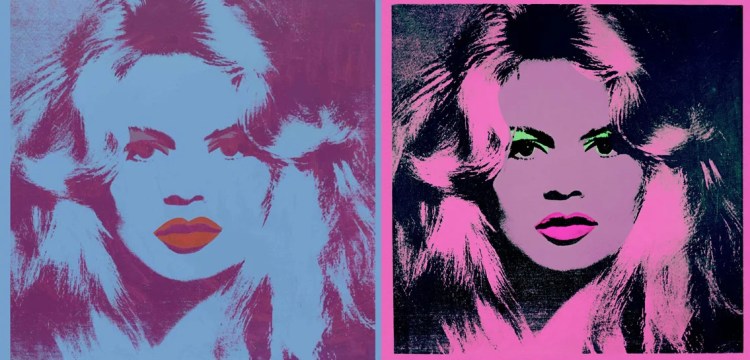

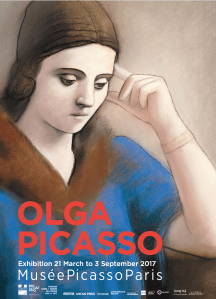

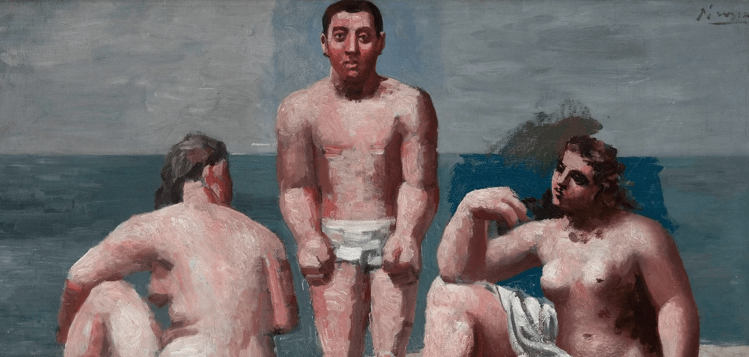

Three months later we were back in the Big Town and headed to the Brooklyn Museum to sample its several new offerings. First up was Rembrandt to Picasso: Five Centuries of European Works on Paper, which featured “more than a hundred European drawings and prints from our exceptional collection, many of which are on view for the first time in decades.”

From the remarkably spontaneous etchings of Rembrandt, through the bold graphite lines of

Pablo Picasso, the exhibition explores the roles of drawing and printmaking within artists’ practices, encompassing a variety of modes, from studies to finished compositions, and a range of genres, including portraiture, landscape, satire, and abstraction. Working on paper, artists have captured visible and imagined worlds, developed poses and compositions, experimented with materials and techniques, and expressed their personal and political beliefs. Other featured artists include Albrecht Dürer, Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Francisco Goya, Berthe Morisot, Edgar Degas, Édouard Manet, Vincent van Gogh, Käthe Kollwitz, and Vasily Kandinsky.

Pablo Picasso, the exhibition explores the roles of drawing and printmaking within artists’ practices, encompassing a variety of modes, from studies to finished compositions, and a range of genres, including portraiture, landscape, satire, and abstraction. Working on paper, artists have captured visible and imagined worlds, developed poses and compositions, experimented with materials and techniques, and expressed their personal and political beliefs. Other featured artists include Albrecht Dürer, Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Francisco Goya, Berthe Morisot, Edgar Degas, Édouard Manet, Vincent van Gogh, Käthe Kollwitz, and Vasily Kandinsky.Except . . .

There was not a single etching or drypoint by James McNeill Whistler, one of the greatest artists ever to put needle to copper.

What . . . the . . . hell.

Other than that, a terrific exhibit.

Next we took in Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, an absolutely fabulous retrospective of a designer who revolutionized fashion, fabrics, furniture, and functional items like lighting fixtures.

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion is the first New York retrospective in forty years to focus on the legendary couturier. Drawn primarily from Pierre Cardin’s archive, the exhibition traverses the designer’s decades-long career at the forefront of fashion invention. Known today for his bold, futuristic looks of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, Cardin extended his design concepts from fashion to furniture, industrial design, and beyond.

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion is the first New York retrospective in forty years to focus on the legendary couturier. Drawn primarily from Pierre Cardin’s archive, the exhibition traverses the designer’s decades-long career at the forefront of fashion invention. Known today for his bold, futuristic looks of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, Cardin extended his design concepts from fashion to furniture, industrial design, and beyond.The exhibition presents over 170 objects drawn from his atelier and archive, including historical and contemporary haute couture, prêt-à-porter, trademark accessories, “couture” furniture, lighting, fashion sketches, personal photographs, and excerpts from television, documentaries, and feature films. The objects are displayed in an immersive environment inspired by Cardin’s unique atelier designs, showrooms, and homes.

The guy was, quite simply, a genius.

We also checked out Garry Winogrand: Color. Winogrand is mostly known for his black-and-white photography of New York icons and street scenes, but the Brooklyn Museum’s exhibit displayed an entirely different aspect of his work. The thing is, given that it was eight slide shows lining two sides of the exhibition room, you sort of had to be there to fully appreciate it.

Bright and early the next morning we subwayed out to Corona, Queens to visit the original Louis Armstrong House Museum, which contained “Louis and Lucille’s vast personal collection of 1,600 recordings, 650 home recorded reel-to-reel tapes in hand-decorated boxes, 86 scrapbooks, 5,000 photographs, 270 sets of band parts, 12 linear feet of papers, letters and manuscripts, five trumpets, 14 mouthpieces, 120 awards and plaques, and much more.”

The digital collection is fun, but the experience of being inside the house was really special. This New York Times piece by Giovanni Russonello captured some of it – including clips from those home-recorded tapes – as does this house tour video.

When we were there, construction was underway across the street on an Armstrong Museum extension. It opened in the summer of 2023, as New York Times culture reporter Melena Ryzik detailed in depth.

You can find anything in Queens. And yet for decades, the Louis Armstrong House Museum has been a well-kept secret on a quiet street in Corona. The longtime residence of the famed jazz trumpeter, singer and bandleader, it is a midcentury interior design treasure hidden behind a modest brick exterior.

The museum’s new extension, the 14,000 square foot Louis Armstrong Center, blends in a little less. It looks, in fact, a bit like a 1960s spaceship landed in the middle of a residential block. By design, it doesn’t tower over its neighboring vinyl-sided houses but, with its curvilinear roof, it does seem to want to envelop them. And behind its rippling brass facade lie some ambitious goals: to connect Armstrong as a cultural figure to fans, artists, historians and his beloved Queens community; to extend his civic and creative values to generations that don’t know how much his vision, and his very being, changed things. It wants, above all, to invite more people in.

With any luck, the Missus and I might get back there to see it one of these days.

Returning to Manhattan, we swung by the Guggenheim Museum to check out Artistic License: Six Takes on the Guggenheim Collection. We thought it was okay, but the Big Town Bigfeet split in their reviews: The Wall Street Journal’s Peter Plagens thought it was a mess, while Roberta Smith was much more kind in the New York Times

Also at the Guggenheim was Basquiat’s “Defacement”: The Untold Story, but the waiting line was a half hour long so we about-faced and strolled up Fifth to the Cooper-Hewitt. Why, I don’t know.

As previously mentioned, the Missus and I remember fondly the days of mustard pot and pop-up book exhibits at the Cooper-Hewitt, but those days are decidedly gone. Exhibit Umpteen: Nature—Cooper Hewitt Design Triennial, in which “sixty-two international design teams . . . are engaging with nature in innovative and ground-breaking ways, driven by a profound awareness of climate change and ecological crises as much as advances in science and technology.”

Yeah – not engaging. We still like Andrew Carnegie’s old 64-room crib, though.

Happily, Jewelry for America at The Met served as a sort of visual sorbet. That left the best for last: Relative Values: The Cost of Art in the Northern Renaissance.

Bringing together sixty-two masterpieces of sixteenth-century northern European art from The Met collection and one important loan, this exhibition revolves around questions of historical worth, exploring relative value systems in the Renaissance era. Organized in six sections—raw

materials, virtuosity, technological advances, fame, market, and paragone—tapestry, stained and vessel glass, sculpture, paintings, precious metal-work, and enamels are juxtaposed with pricing data from sixteenth-century documents. What did a tapestry cost in the sixteenth century? Goldsmiths’ work? Stained glass? How did variables like raw materials, work hours, levels of expertise and artistry, geography, and rarity, affect this? Did production cost necessarily align with perceived market valuation in inventoried collections? Who assigned these values? By exploring different sixteenth-century yardsticks of gauging worth, by probing extrinsic versus intrinsic value, and by presenting works of different media and function side-by-side, the exhibition captures a sense of the splendor and excitement of this era.

materials, virtuosity, technological advances, fame, market, and paragone—tapestry, stained and vessel glass, sculpture, paintings, precious metal-work, and enamels are juxtaposed with pricing data from sixteenth-century documents. What did a tapestry cost in the sixteenth century? Goldsmiths’ work? Stained glass? How did variables like raw materials, work hours, levels of expertise and artistry, geography, and rarity, affect this? Did production cost necessarily align with perceived market valuation in inventoried collections? Who assigned these values? By exploring different sixteenth-century yardsticks of gauging worth, by probing extrinsic versus intrinsic value, and by presenting works of different media and function side-by-side, the exhibition captures a sense of the splendor and excitement of this era.The exhibit was a total gas: It basically tells you how many cows it would take to buy each item (one cow = 175 grams of silver or 5,350 loaves of rye bread in Brussels).

So, for example, this 1585 Bohemian Tankard would have set you back 158 cows.

This 16th Century German stirrup cup on the other hand? A bargain at 1/8 cow. (Not sure how that gets handed over.)

That exhibit alone was totally worth the two cows admission price to The Met.

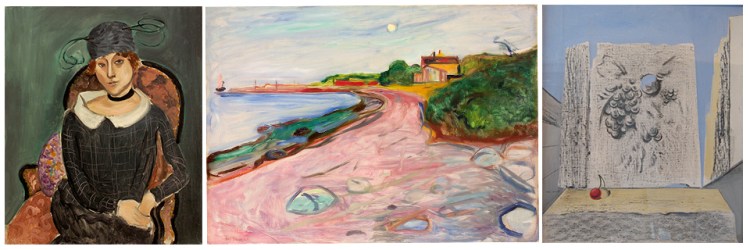

On the way back to Boston, the Missus and I made another pit stop at the Wadsworth Atheneum, this time to catch From Expressionism to Surrealism: Highlights of Modern Art from the Collection.

A special installation of treasures from the Wadsworth’s collection including works by Ernst, Munch, Matisse, Picasso, and Rousseau. This intimate presentation of works of art made between 1900 and 1950 illustrates expressionist and surrealist approaches to painting.

(Above: Henry Matisse, The Ostrich-Feather Hat, 1918. Edvard Munch, Aasgaardstrand, c.1904. Max Ernst, Still Death.)

After that we checked out The Bauhaus Spirit at the Wadsworth Atheneum, which “is expressed throughout the Wadsworth’s collection in art, furniture, and architectural design.”

Such as . . .

Then we went from the Bauhaus to our house.

• • • • • • •

The Missus and I trundled back to the Big Town in December and just our luck, we arrived on an official Gridlock Alert Day, which meant it took us fully 60 minutes to crawl from 71st and First to 32nd and Fifth.

Undaunted and safely ensconced in our moderately priced hotel, we first headed to the FIT Museum, which featured Paris, Capital of Fashion.

Paris, Capital of Fashion opened with an introductory gallery that places Paris within a global context, presenting it in dialogue with other fashion capitals, especially New York. By presenting an original couture suit by Chanel together with a virtually identical licensed copy sold by Orbach’s department store, for example, the exhibition demonstrated how the idea of Paris fashion “works” across fashion cultures, appealing to elite American women and making money for American manufacturers and retailers..

Entering the main gallery, visitors were immersed in the mythic glamour of Paris fashion as the exhibition traced a trajectory from royal splendor at Versailles to the spectacle of haute couture today. An 18th-century robe à la française was juxtaposed with a haute couture creation for Christian Dior, which was inspired by Marie Antoinette.

From there we subwayed uptown to the Bard Graduate Center to catch French Fashion, Women, and the First World War.

In moments of great upheaval—such as in France during the First World War—fashion becomes more than a means of personal expression. As women throughout the country mobilized in support of the war effort, discussions about women’s fashion bore the symbolic weight of an entire society’s hopes and fears. This exhibition represents an unprecedented examination of the dynamic relationship between fashion, war, and gender politics in France during World War I.